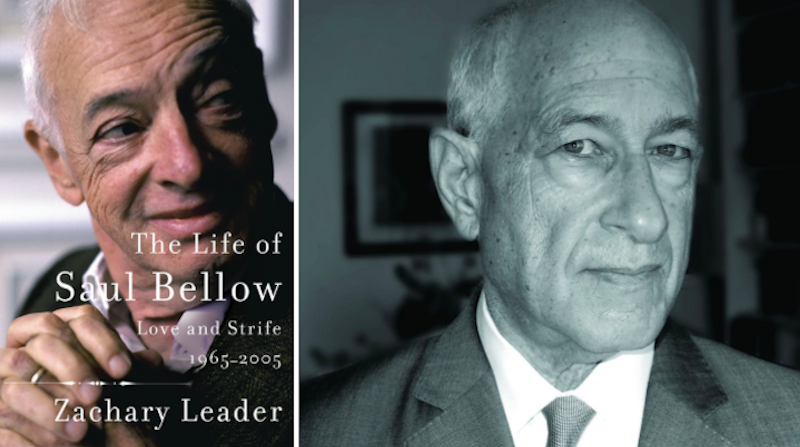

Zachary Leader’s The Life of Saul Bellow: Love and Strife 1965-2005 is published this month. He shares five literary lives with Jane Ciabattari.

Coleridge, 2 volumes (Early Visions, 1772-1804 and Darker Reflections, 1804-1834) by Richard Holmes

Here is the most traditional and popular of life-writing forms, a cradle to grave biography, as attentive to the writing as to the life. Coleridge was in many ways a mess—an opium addict, a feckless husband and father, a plagiarist, frequently blocked, tormented by sexual guilt. Holmes is a pioneer of the “footsteps” approach to biography, an acute critic and a compelling storyteller. He details all Coleridge’s faults, yet views his life sympathetically, as loveable, admirable, a master spirit of the age.

Jane Ciabattari: Holmes’ “footstepping” required putting himself in the physical locations of his subjects—a process he refers to as “tracking.” His pursuit of Coleridge took him to “the English West Country and the Lake District, to Germany, to Italy, to Sicily, to Malta, and finally to a quiet garden on Highgate Hill in London,” he notes in a 2014 essay in the New York Review of Books. You express doubts about this method in your acknowledgments to this second volume of The Life of Saul Bellow, yet note it was good to live in the Chicago apartment building where Bellow lived, and walk to his office at the University of Chicago’s Committee on Social Thought, while working on this book. What other physical locations did you visit? And I’m curious to know what your doubts might be about Holmes’s method.

Zachary Leader: I’ve done a fair bit of tracking of Bellow, not just in Chicago, where I visited all his homes and haunts, but in Montreal and Lachine, where he was born and lived the first eight years of his life. Other places I’ve visited are Madison, Wisconsin, where he was a graduate student in anthropology; New York and Princeton, where he taught while finishing The Adventures of Augie March; Bard College, where he went after Princeton, and Tivoli in upstate New York, a setting for Herzog; Minneapolis, where his second marriage unravelled disastrously; Manhattan; Brookline and Vermont, where he had homes and lived the last twelve years of his life. In Paris, I tracked down the apartments he lived in and the cafes he frequented during his stay in 1948-50; I took holidays in southern Spain, near where he holidayed. Alas, I never made it to Puerto Rico, where he taught briefly at the university, or St. Martin, in the Caribbean, devastated by the recent hurricane, where he nearly died from fish poisoning. My wife often complained that we only went to places where Saul Bellow went—but who can complain about Paris and southern Spain?

My doubts about the footsteps approach apply to some locations not others. I’m okay with Wordsworth’s Lake District or Bellow’s Paris, but Robert Louis Stevenson’s California, a location tracked by Holmes, is more problematic. Hard to see today’s Sacramento as a “city of gardens in a plain of corn,” which is how Stevenson described it. In the parts of Los Angeles where I grew up, almost everything has changed from Stevenson’s time—even from the time of my childhood.

Chronicles, Volume 1 by Bob Dylan

A very different sort of life, a memoir or autobiography with zero interest in chronology. The life and the work are evoked in vivid vignettes. Very little is said about the best-known or breakthrough albums, about going electric in 1965, about sex or drugs or the March on Washington or the motorcycle accident or the short-lived Christian conversion. Much is surprising, especially about what he likes: Dave Van Ronk and Woody Guthrie, of course, but also Harold Arlen, Ricky Nelson, polka, Harry Belafonte. The voice of the memoir is that of the songs—glancing, funny, poetic, or almost poetic. We learn how the life is lived, a lonely, ruminative, wary life, and how the songs are created. Reassuring for fans like me to see how well written the book is and how original.

JC: So much of this roundabout memoir focuses on Dylan’s early days in the Village, starting out as a talented outsider. (I’m reminded of his Nobel acceptance speech, which focused on earliest influences—Buddy Holly, who he saw only days before he died; Leadbelly, folk music; and Moby-Dick, All Quiet on the Western Front, The Odyssey, with his final line, “Sing in me O muse, and through me tell the story.”) What’s your favourite Dylan-told story from this first volume of his Chronicles?

ZL: I especially like Dylan’s freestyle accounts of how the songs got written, as teasing as the songs themselves. “The Disease of Conceit,” for example, a song I especially like, might, he recalls, have been triggered by the arrest of the popular Baptist preacher Jimmy Swaggart, defrocked from his congregation for refusing to give up preaching. When Swaggart was caught with a prostitute, he wept for forgiveness, but he also broke his promise to stay out of the pulpit. Dylan comments: “The story didn’t make any sense. The Bible is full of these things. A lot of those old kings and leaders had many wives and concubines and Hosea the Prophet was even married to a prostitute, and it didn’t stop him from being a holy man.” Dylan quotes unused lyrics to the song, perhaps sung by Swaggart’s prostitute, whom he imagines as “a damsel of tempting statuesque beauty”: “There’s a whole lot of people dreaming about the disease of conceit, whole lot of people screaming tonight about the disease of conceit. I’ll hump ya and I’ll dump ya and I’ll blow your house down. I’ll slice into your cake before I leave town. Pick a number—take a seat, with the disease of conceit.”

The Letters of Evelyn Waugh, ed. by Mark Amory

Evelyn Waugh’s letters are better than his diaries because they were written in the morning, before he began drinking. The diaries were written in the afternoon. Waugh was neither a pleasant drunk nor a pleasant man. A self-confessed bigot, bully, reactionary, and philistine, he was also very funny, very clever, and a brilliant writer. To his wife, during the war: “I know you lead a dull life now… But that is no reason to make your letters as dull as your life. I simply am not interested in Bridget’s children.” Of William F. Buckley, Jr.: “Has he been supernaturally ‘guided’ to bore me? It would explain him.” Beneath the rudeness and the pomposity (“almost always an absolutely private joke against the world”) lies despair.

JC: What do you make of Waugh’s letters in reaction to the reception of Brideshead Revisited?

ZL: My favourite Waugh letter about Brideshead was written on 19 May 1945 to his wife, Laura, and though it doesn’t mention the novel, clearly derives from its enormous success. It begins: “I think I have just bought a castle. I hope you will approve.” As a bonus, here’s Kingsley Amis to Philip Larkin on Brideshead. Amis writes from Oxford in 1946, where he and Larkin were undergraduates at the same college. Larkin has just written to disparage the novel. Amis, too, dislikes it, singling out “this sort of thing”:

Over the Knobworthy mantelpiece was a supurb Schleimikunt of the Klapstruk period, flanked by Pederasti engravings. I took a Zebbraterd cigarette from the walnut Piscipant box on the Kokopessari table, on which also stood a red sandstone head of Borl Sung Lo, dating from the mid-D’ung dynasty, and went across the rich Pewbicke hair carpet to admire the hand-printed edition of the works of Uterus Menstruensis. On the bookcase lay an autographed score of Cloaca’s “Il Fluido della Testiculo” given to the composer by my friend at the first performance at the Twathaus in Randenburg.

Journals of Dorothy Wordsworth: The Alfoxden Journals 1798, The Grasmere Journals 1800-1803, ed. by Mary Moorman

As her journals make clear, Dorothy Wordsworth provided her brother William with starting points for some of his best-known poems. Super-responsive to landscapes and atmospheres, she described the things she saw, including the people who passed their cottage (vagrants, tinkers, travellers), in terms so vivid that William at times borrowed them word-for-word. She herself never built her observations into poems, which is in part what makes her journals so sad and moving. She loved and served William all her life and never married. The journals describe with emotion coming across his half-eaten apple core, his breathing, his “cool and fresh” smell. On 31 May 1802, at thirty, she records: “My tooth broke today. They [her teeth] will soon be gone. Let that pass I shall be beloved—I want no more.”

JC: The Alfoxden Journals were written while her brother and Coleridge were working on The Lyrical Ballads, so might it also be said she influenced Coleridge as well? Wordsworth refers to a walking tour the three of them took that included a conversation about the shaping of “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” with its opening lines:

With my cross-bow,

I shot the albatross.

Wordsworth suggested Coleridge include “tutelary spirits” avenging the crime of the killing of the black albatross. It’s tempting to wonder what Dorothy suggested, given her gift for inspiring her brother. Might she have been a poet herself in modern times?

ZL: According to Holmes, “many of [Dorothy’s] Journal entries describing the Quantocks landscape, and especially effects of sun and moonlight, are mirrored by phrases in Coleridge’s ballads, though it is impossible to tell who was influencing whom.” As for your second question, I don’t see why a modern-day Dorothy couldn’t have been a poet, but it is also easy to imagine a set of modern-day circumstances leading her to believe she wasn’t up to it. The inhibiting influence of a modern-day William, a beloved older brother who was also a poetic genius, isn’t impossible to imagine. Who knows?

Ravelstein by Saul Bellow

“You don’t easily give up a character like Ravelstein to death.” So writes Chick, the novel’s Bellow-like narrator. Ravelstein is transparently Bellow’s great friend the political philosopher Allan Bloom. The novel is a fictional memoir, one Bellow claims Bloom urged him to write, as Ravelstein urges Chick to write his life, being “as hard on me as you like.” It’s a wonderfully life-like portrait, according even to those of Bloom’s friends who deplored its outing of his homosexuality. “Do it in your after-supper-reminiscence manner,” Ravelstein urges Chick, “I love listening when you’re freewheeling.” Freewheeling neatly describes the novel’s narrative, which resists the forward movement of the life-story, the tragic deathbed ending. Bloom, like Ravelstein, valued the quality of life, its intensity rather than its duration. He defied death, the aim also of the novel, written by an author in his late eighties.

JC: Bellow was eighty-four when he published Ravelstein, four months after his daughter Rosie was born. Once again he’s created a rich complicated character based on an intimate friend, Allan Bloom, and holding to the measure of his art rather than keeping secrets. (As you note, and explore in your new volume, Ravelstein ignited a controversy over Bellow’s writing of Ravelstein’s homosexuality and his death from AIDS, seen by some as a betrayal of Bloom.) Upon rereading, the novel’s explosive energy endures. As you point out, Bellow defies he arc of life in that final section; rather than ending at his deathbed, we see Bellow’s narrator watching Ravelstein in his Hyde Park apartment, dressing to go out to the accompaniment of Italian Maiden in Algiers pouring from his hi-fi:

He loses himself in sublime music, a music in which ideas are dissolved, reflecting these ideas in the form of feeling. He carries them down into the street with him. There’s an early snow on the tall shrubs filled with a huge flock of parrots—the ones that escaped from cages and now build their long nest sacks in the back alleys. They are feeding on the red berries. Ravelstein looks at me, laughing with pleasure and astonishment, gesturing because he can’t be heard in all this bird-noise…

You don’t easily give up a creature like Bellow to death. The concluding chapter of your biography shows us the complicated mixture of love and strife in Bellow’s last years, as he develops dementia, enjoys his daughter, struggles with his writing amid memory lapses, maintains a teaching role, with the help of co-teachers, and maintains “a world of strife and jostling.” What were your primary sources for these intimate details?

ZL: I was very fortunate. Everyone talked to me: all the family, the ex-wives, the doctors, carers, colleagues, editors, friends, ex-friends. Janis Bellow, Bellow’s fifth wife and widow, showed me pages from her diary of Bellow’s last years. I had access to all Bellow’s correspondence. James Atlas, who figures prominently in the second volume—as subject as well as source—published a painfully intimate memoir of his relations with Bellow. In some instances, I was given diametrically opposed accounts of feelings and events. I’ve done my best to be considerate as well as truthful.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·