“…nor had I understood til then how the shameless vanity of utter fools can so strongly determine the fate of others”

*

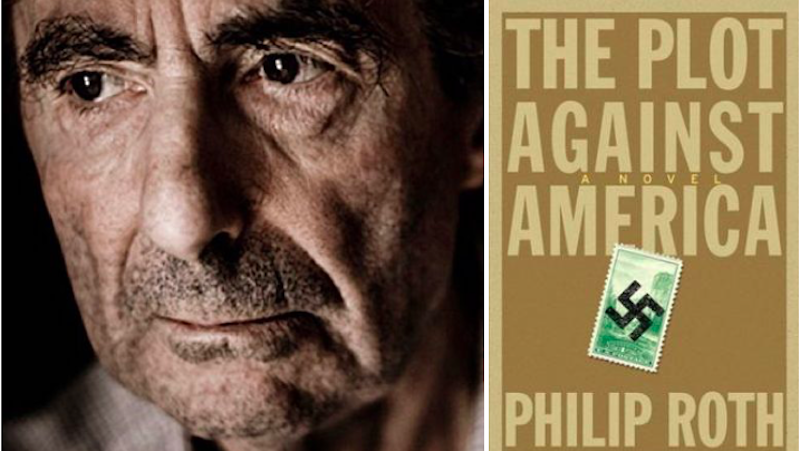

“…a fable of an alternative universe, in which America has gone fascist and ordinary life has been flattened under a steamroller of national politics and mass hatreds … The novel is sinister, vivid, dreamlike, preposterous and, at the same time, creepily plausible. Roth seems to be taunting, ‘You think swastikas are only for other countries?’ And you turn the pages, astonished and frightened.

There is a solid tradition in American letters of novels like this, phantasmagoric pictures of a United States whose every promise has been turned upside down — jeremiads about America’s ability to transmute overnight into a fascist monstrosity…the classic of classics has always been Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here from 1935. The very title of Lewis’s novel entered long ago into the American language, a sardonic phrase, mocking the sweet naïfs who persist in believing that evil dwells anywhere but at home.

…

“Fascism took over most of continental Europe during those years, and this event was terrifying not just for the obvious reasons but also because every country in Europe seemed to have generated a fascist movement of its own, drawing on national idiosyncrasies and charming folk costumes — such that, after a while, the very existence of local traditions and funny hats came to seem positively sinister … But the genuinely scary prospect in America was a fascism that might draw on something more than immigrant peculiarities — a fascism thriving on the ‘patriot’ legacies of the American Revolution and the cornball kitsch of surly folk cultures from this or that region of the country. A fascism in red, white and blue. That was Lewis’s fear. And it is Roth’s.

…

“At 4 a.m. the Republicans officially nominate their candidate. And the narrator abruptly reverts to his childhood memories — the recollections of the 7-year-old who, until that moment, had been fast asleep, together with his older brother:

‘No! was the word that awakened us, No! being shouted in a man’s loud voice from every house on the block. It can’t be. No. Not for president of the United States.

‘Within seconds, my brother and I were once more at the radio with the rest of the family, and nobody bothered telling us to go back to bed.’ The neighbors pour into the street in their pajamas and nightdresses, crying in outrage and disbelief, ‘Hitler in America!’

…

“But I want to return to this matter of Roth’s tone. The dignity, the formality, sometimes even the hint of academic reserve in the narrator’s voice produce two vibrating timbres, and these dominate the novel — a timbre of explosive anger, and, when the clapper swings to the other side, a timbre of husky pathos. The anger is political, refreshing in its pealing clarity — an anger at fascism and at anti-Semitism. And then the anger gives way to the anxieties of a little boy, overwhelmed by childhood fears, trying to make sense of events…

…

“Not once in any of this does Roth glance at events of the present day, not even with a sly wink. Still, after you have had a chance to inhabit his landscape for a while and overhear the arguments about war and fascism and the Jews, The Plot Against America begins to rock almost violently in your lap — as if a second novel, something from our own time, had been locked inside and was banging furiously on the walls, trying to get out … Roth shows us how swiftly the rights and democratic customs of American life are lost.

…

“The Plot Against America is not an allegorical tract about the present age, with each scene or character corresponding to events of our own time. I think that in composing his novel, Roth has simply run his eye across the modern horizon, and gathered in the sights, and rearranged them in a 1940’s kaleidoscope. And, astonished by the shapes and colors, he has taken a deep breath and let himself feel what he really feels.”

–Paul Berman, The New York Times, October 3, 2004