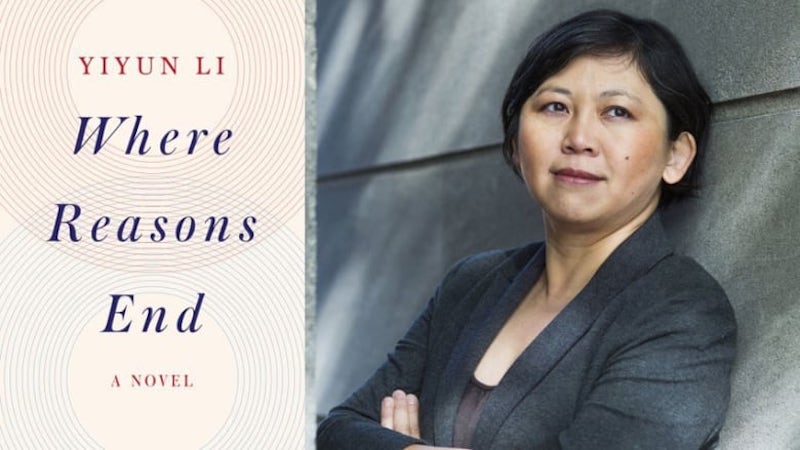

Yiyun Li’s Where Reasons End is published today. She shares five books about children who awed her.

“A few years ago I encountered a line in Surprised by Joy, by C. S. Lewis: ‘I fancy that most of those who think at all have done a great deal of their thinking in the first fourteen years.’ I showed the quote to my teenage son, who said he agreed with it entirely. Having been called precocious when I was young, having raised children called precocious by others, I had by then developed an allergy to that label, and I had a bias against child characters that are easily categorized as precocious in fiction. But the Lewis’s quote prompted me to read and reread novels with characters that are simply children who have done a great deal of their thinking. Here are five novels featuring child characters who have awed me, frightened me, or taught me about humility.”

The Present and the Past by Ivy Compton-Burnett

All the children in all the novels by Compton-Burnett speak with insane articulateness. The five children in this novel could easily impale grownups—their elders and their readers—with words, and perhaps they would even observe their victims with impartial curiosity. They can be called precocious, or unreal by suspicious readers, but I would like to borrow Elizabeth Bowen’s phrase about Compton-Burnett’s work—”inner realism”—to describe these children. Their inner realism reflects “a higher level of consciousness,” yet they are children through and through. They are children who have done their thinking without our assistance.

Jane Ciabattari: In the first chapter, three of the five children in the book from two mothers and the same father are focused on a hen being pecked to death by the flock (an ironic image of the “pecking order” that emerges in the novel). Each reacts in an individual way. Henry is eight, “with something vulnerable about him that seemed inconsistent with himself.” His sister Megan, seven, has “sudden nervous movements, and something resistant in her that was again at variance with what was beneath.” Toby, at three, has “a withdrawn expression, consistent with his absorption with his own interests.” After the hen dies, each child has a specific reaction consistent with this early description. Then two older boys join them, each etched clearly. Fabian is thirteen, with clear grey eyes that recall his sister and Guy, eleven, who has a “habit of looking at his brother with trust and emulation.” How do you think Compton-Burnett is able to make each one so distinct?

Yiyun Li: Compton-Burnett’s novels are carried by dialogues, and all characters contribute, sometimes engaged with one another, sometimes talking in parallel. In the first chapter of this novel, all five children establish themselves by the way they speak. Henry is a dubber of everything going on in the world. He adds the soundtrack while watching the hen being pecked, “It will soon be dead. It must be having death pangs now.” Megan pays attention to people around her, she listens and responds, and when she speaks she philosophizes. Responding to Henry’s comment on a hen’s death pangs, she says: “I don’t think the hen is having them. It seems not to know anything.” Toby, though still babbling in the manner of a toddler (and acting with the authority of a toddler), makes observations that must satisfy his inner writer. While throwing his cake into the pen, he says, “All want one little crumb. Poor hens.” Fabian, on the cusp of leaving his childhood, is unsparing toward both children and grownups. “Why should I talk like a child, when my life prevents me from being one?” he asks. Guy, looking up at Fabian yet not being able to achieve the same clear-eyed distance, responds with a wishful question, “Would having a real mother make us more childish?”

Sometimes childhood in literature is portrayed as a prelude that offers all those clues to how characters turn out later in life, why they do what they do. These five children do not live in any prelude but the present. They are not prototypes of their grownup selves.

The House in Paris by Elizabeth Bowen

Two worlds coexist in this novel. The one occupied by multiple love triangles among the grownups is exquisitely drawn by Bowen, but it’s the one shared by the two children, Leopold and Henrietta, that brings a Shakespearean intensity to the novel. Even more impressive is that Henrietta, at eleven, appears to be the perfectly everyday girl, carrying a stuffed monkey and reading glossy magazines. But what deceptive depth children have!

JC: Henrietta is eleven, traveling to visit her grandmother in the South of France, when she spends a day in Paris with family friends and encounters nine-year-old Leopold, who has come to meet his mother for the first time (his father is dead). “Henrietta regretted that Leopold was not a girl,” Bowen writes. In the course of the day, Henrietta, who is immensely observant, learns family secrets. The strained relationship between the two children is fascinating. Which moments strike you as most revealing of their relationship?

YL: “It is never natural for children to smile at each other: Henrietta and Leopold kept their natural formality.” This happens at the beginning of the novel, an astute observation. Most grownups, like Miss Fisher in the novel, expect children to be natural companions. There is nothing natural in that expectation. Smiling at a stranger is an acquired skill. The two children torment each other relentlessly, sometimes simply by being who they are. “The bastard’s pride” of Leopold is crushed by Henrietta’s “displeased cool manner”: “she showed he was nothing to her.” And in turn, Leopold creates a life in England with his mother that excludes and agonizes Henrietta. “There seemed no doubt he and she would go to England together to live a demi-god life there, leaving Henrietta forgotten, luckless, cold.”

Harriet Said by Beryl Bainbridge

That schoolgirls are not sweet or innocent is not news, but in this novel the two girls not only have done their share of thinking and feeling but also have gone on to invent psychologically necessary scenarios to serve themselves. One British publisher rejected the novel, saying “I fear that even now, a respectable printer would not print it.”

JC: In Bainbridge’s first novel her thirteen-year-old narrator and her fourteen-year-old friend Harriet target Peter Biggs for their fantasies, tagging him with the nickname “the Tsar.” “Slightly unsober, slightly disheveled, always elegant, he swayed moodily past us through all the days of our growing up,” Bainbridge writes. But when they watch him in an intimate moment with his wife, each of them experiences a loss of innocence of sorts. How do you feel about their retaliation?

YL: Without giving away the plot, I would say that the two girls remind me how lucky we are that life doesn’t often choose to go to the extreme. It happens, but it happens rarely. The powers and powerlessness the two girls feel at their age, the rawness of the experience brought by the world that has long become timid and lukewarm to accommodate their passions—I can only say I’m awed by both of them.

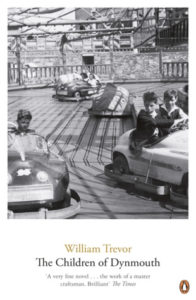

The Children of Dynmouth by William Trevor

The fifteen-year-old Timothy Gedge in this novel can make anyone’s blood turn to ice. When he trails behind a pair stepbrother and stepsister, a few years younger than him, one cannot but feel for the children of Dynmouth, and one cannot but extend the fear and empathy to the children of the world.

JC: Timothy seems omnipresent, needy and unpleasant, even frightening, driven by his solitude into blackmailing townspeople and imagining himself winning attention at a talent show. Trevor is a master. What do you think he’s trying to tell us about this isolated teenager?

YL: I wonder if a majority of population, other than saints, all share something with Timothy Gedge. Some are better at hiding the Timothy Gedge in them; some are better at regulating; some, perhaps by luck or by willower, have exorcised Timothy Gedge from themselves. He is a nightmare, but not a catastrophic nightmare. Trevor is a master in writing about the malicious and the deceptive in the mundane, and the novel is a good reminder that most of us are not free from everyday nightmares.

99 Nights in Logar by Jamil Jan Kochai

Kochai was my former student, and I’ve watched this novel grow from the beginning. It’s set in rural Afghanistan, with machine-gun carrying teenage boys chasing a dog running away with the narrator’s thumb in his stomach. The book is funny and sad and I remember, reading the draft in installments and mistaking the penultimate chapter as the ending, thinking that it couldn’t be a more perfect ending. But the real ending came in the next installment, which made me laugh and tear up at the same time. The narrator, a twelve-year-old boy named Marwand, reminds me of Don Quixote, and how many child characters can live up to that standard!

JC: Talk in Marwand’s family compound, Kochai writes, “always seemed to circle back to war.” When Marwand returns to his home village, he has a fateful encounter with the guard dog, Budabash, and then sets out to track him down. Quixote is an interesting parallel. How would you describe the goal of Marwand’s journey?

YL:That elusive Budabash—Is it to Marwand the glory of knighthood to Quixote? Is it an ongoing tale that leads Marwand from night to night, like those never-ending stories in The Arabian Nights? Or perhaps, more aptly, is it not a landlocked Moby-Dick, carrying away a part of Marwand into wildness? There are many ways to describe Marwand’s journey. I hesitate to give too much of a metaphorical reading because it’s a novel, like Don Quixote, to be read and relished.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·