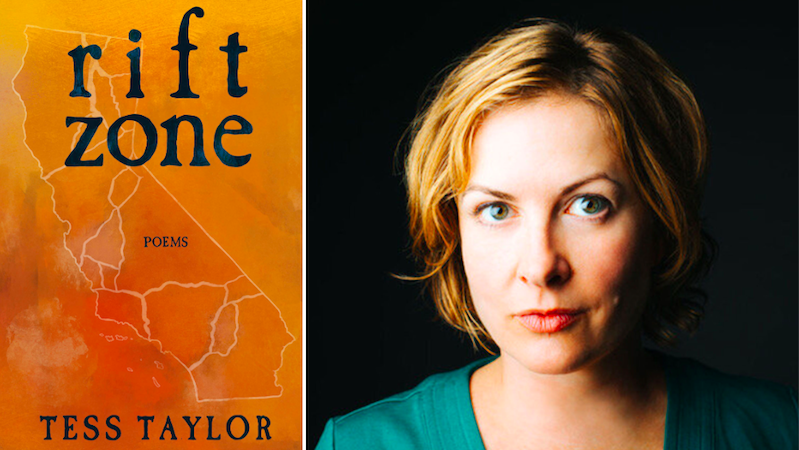

Tess Taylor’s new poetry collection Rift Zone is published this month. She shares five books about writing place in a time of crisis.

Wintering Out by Seamus Heaney

Seamus Heaney wrote this rich book about place and belonging in the late 60s and early 70s, as the sectarian violence of the Troubles was breaking out all over Northern Ireland, where he then lived. Strangely, he also finished some of the poems during a sabbatical in Berkeley. These are poems for home dialect, home place, but also for trying to find a way, in a violent time, to take a long view. In Rift Zone, when I name geologic time or deep California history, I’m trying to help us stay connected to something bigger than the present moment.

Jane Ciabattari: Heaney’s title comes from “memories of cattle in winter fields,” he said in an interview with Dennis O’Driscoll. “Beasts standing under a hedge plastered in wet, looking at you with big patient eyes, just taking what came until something else came along. Times were bleak. The political climate was deteriorating. The year the book was published was the year of Bloody Sunday and Bloody Friday.” It was also the year after his Berkeley sabbatical, a time during which Heaney concluded poetry could be “a force, almost a mode of power, certainly a mode of resistance.” Do you see these moments facing poets today?

Tess Taylor: There’s so much to consider in these questions, and even thinking through them is useful now, as we all look for models of how poets and artists (and all of us really) can respond to enormous civic stress, violence, and adversity.

Heaney is discussing both patience and resistance, the way they can be linked forces. “Wintering out” is also something farmhands did on land, paying no rent and just abiding, until work started again. It’s a mode that isn’t just passive but is about low, deliberate survival. Holding fast. I mentioned that Heaney wrote some of these poems in Berkeley. In some counterpoint, in the first year after the 2016 election I was not in Northern California, but in Belfast, Northern Ireland, a place where there are also rifts and fault lines right under the surface of civic life. People well know that there are tides that can hurt or heal. There’s a very conscious awareness in the air that peace is an active, deliberate process, a kind of slow work.

I think American poets are asking ourselves: In this moment of open rupture, how much do we protest, and how much do we take the long view? Or is there a kind of poetry that offers its protest precisely by helping us to take the long view? I think one way to protest the present is to link ourselves to both our past (even to its previous brokennesses) and to the future we hope for. We need to find regenerative spaces for our imagining. I see art as a place where we can craft endurance, perhaps even some renewal. The rift in Rift Zone comes from the tearing open, the rupture, the heave between plates. But it also echoes a line from Heaney’s famous essay “Government of the Tongue”: “In the rift between what is going to happen and whatever we would wish to have happen, poetry holds attention for a space.” I think the role of poets is to create that kind of attention: to offer us some place, where, standing in the tear, we can reroute ourselves.

Trophic Cascade by Camille Dungy

This wonderful book of poems about ecology and motherhood and race mixes nature and culture and ecosystem and human longing in ways I think are very compelling. Dungy has wonderful poems to an unborn child and to spruce gum eucalyptus, and the poems are at once fierce and dreamy.

JC: in her title poem, Dungy writes about the reintroduction of gray wolves to Yellowstone, and the cascade of returns that follow—weasel, water shrew, vole, hawk, falcon, bald eagle, kestrel. Her final lines are profound. How do you interpret that shift she makes?

Don’t

you tell me this is not the same as my story. All this

life born from one hungry animal, this whole,

new landscape, the course of the river changed,

I know this. I reintroduced myself to myself, this time

a mother. After which, nothing was ever the same.

TT: I love this poem, too! They say that the reason that people are so tired when they become parents is because, when you become a parent, your brain fundamentally rewires itself. This is true for adoptive parents too—the brain is learning so much that within a year so many major neural patterns change that you are actually, in some important ways, a different person. I might hazard: To become a mother of small beings is to realize immediately that you are deeply animal, connected to all the mothers through time, back into the dark chain of the past. It is to also realize, profoundly, that everyone alive was born, was mothered, or parented, was brought up (even if in flawed or radically imperfect ways) through acts of profound care. It also, I think, makes us aware of our common vulnerability, on the planet, as beings that need care. For instance, when my children were very small, I realized immediately that their health, that our health, was a community function—that we would all get the same cold as everyone in the preschool, as everyone who tended my children. This is to say: we become porous. There is and never was an “us and them”—the health of everyone around us is intimately linked to our own. Anyway, Camille, I know, sees this too. This is the landscape—and the shift in knowing—that I see her reading out.

Praise by Robert Hass

This was one of the first books of poems I ever loved, and growing up as a kid in the Bay Area, this work excited me most—the chance to name and long and yearn in a landscape I knew well. “Smell of wild fennel, high loft of sweet fruit in the high branches/ of the flowering plum.” Who could not love that?

JC: Or, in a poem like “Meditation at Lagunitas,” his concluding lines about a woman he’d made love to:

But I remember so much, the way her hands dismantled bread,

the thing her father said that hurt her, what

she dreamed. There are moments when the body is as numinous

as words, days that are the good flesh continuing.

Such tenderness, those afternoons and evenings,

Saying blackberry, blackberry, blackberry.

How does his blending of sensual detail and abstract image work?

TT: Oh, this poem, which I read at sixeen with my old friend Jasmine for hours at Cafe Roma, across from Monterey Market in Berkeley! Oh this poem and the memory of reading the poem which is also a memory of the desire to read poetry, the desire for poetry itself. I remember so much! I love the way this passage blends the corporeal with the “numinous”—a word that means spiritual, but also comes from “numen” which means the “spirit of a place.” This is much the way “genius” doesn’t really mean “very smart” but more means “the god of a particular talent”—each of us has a genius, and each place has a numen, too. Hass was among the first people to name for me in literature the numen of the place I already was, which was Berkeley, Northern California. I saw in this poem my own life and home better—the weedy, wayward land of wild blackberries and herb-scented sun. For me the sensuality was in learning to praise both the numen but also the good bread, and also the weedy blackberry, clambering on all the abandoned lots around us. This poem enacts naming—whether numen or blackberry or pain or bread—as tenderness. Naming as tenderness. Naming as radically imperfect tenderness. I still think that.

Heaven’s Breath by Lyall Watson

This is the kind of book that enchants me—an out of date, now reprinted, book about the natural history of wind! I love to read it feeling that it is beyond reviewing and just for abstruse pleasure. A book about wind! Sidelong and also brilliant. How wind moves over the world, how it carries insects and birds and directs weather, how it fills our myths and dreams. Among the many charms of this book is a list of cultural names for wind, that range from Santa Ana to mistral to simoom. It’s not so much that this made its way into a book of poems about fault lines and geology and American violence. But this had a ranginess and loft. It weaves ecological truths and social ones together. Also, this book feels like a bit of a sanctum of private pleasure.

JC: I’ve been walking Willow Lane in Cotati during the COVID-19 lockdown in California, photographing a herd of sheep, with their frisky baby lambs, and posting images on Instagram. The other day I captured the herd lying together in a circle, all facing into the afternoon wind, which led me to take some time pondering wind, and how humans and animals react. Which winds have been most dramatic in your life? The wildfire winds we’ve both experienced in recent years?

TT: Yes. Our fall winds here in California are really something, and they stir us up—I think of October as a time of baleful heat and dread. I felt this even before the fires got so regular, so intense. I always feel a sort of insufferable restlessness in that season—either of dry heat or of winds, and of sudden eager desire for rain. There are wonderful parts of October here, when the dry heat holds. But often it feels stale, polluted, insufferable. Our various basins fill up with bad air from China, which is, paradoxically, caused by our desire for crappy plastic things and bad clothes that are then manufactured there. Often, in California, we are lucky to have that wind blow elsewhere, but in October the global winds are such that we get a cloud of pollution straight from Chinese factories. I read recently that consumer demand for things things things has meant that there are two to three more bad air days in Los Angeles and the Bay Area each fall. This is actually a reminder of how we are linked—we don’t get away from any of these things. We are linked by wind. By breath. By climate. There are parts of our own barometries we do not yet understand.

Surfacing by Kathleen Jamie

Nature and culture, nature and culture, how we meet the wild, how we change the climate, how the climate changes us. I guess I’ve got a one-track mind, except the track has so many wonderful variations. The Scottish poet Kathleen Jamie is one of my favorite living poets, but she’s also a tremendous essayist, and in this book, she examines things as varied as Inuit land where warming is unburying ancient tools, to her own attempt to unbury memories of travels long gone, moments in her youth that both elude and shape her. In her hands moving an essay collection between the reported, the felt, the remembered, and the seen feels deft. She’s a compassionate witness. I recommend her to everyone.

JC: Jamie makes such careful, leisurely observations. Like this: “After 30 minutes or so, I could see colors better, until the haze distorted them. Details emerged. How had I failed to notice the three grass stems next to my right knee, bound together by a ball of spiderweb? When a pale bee entered a fireweed flower, it was an event.” Do you think this time of slowing down, “sheltering in place,” will encourage all of us to be more observant of the natural world?

TT: Jane, that’s one of my hopes, if one is allowed to dare to hope even in the midst of this hard, hard season. For those of us that are waiting in the slowness, maybe this slowness will give us time to imagine, to give us permission to dream and see. In my own life: Our own circuit has shrunk. We are very much here. We are here now, here now, here now again. Yes we work hard, but also we circle the neighborhood on afternoons and weekends when there is nothing but time. In some irony: I wrote a book about home. I was going to be on a plane every week, launching this book by going elsewhere, again and again and again. Now I am not. Again and again I explore this small neighborhood, the hilly graveyard behind our house. I have learned the names of new plants, “wake robin” and “scotch broom” and “bunya bunya.” The birdcalls are tremendous. This morning, I could hear the frogs in the stream up the hill in the graveyard. This stream is the same one, which is, by the way, buried to run under my house. I began to imagine how, if ever, we could unbury our stream. I began to hear my relationship to those frogs.

We all miss so much right now, but how can we build connections to the places we are, sink into them, learn their shapes? “Relationship”—the state of being connected. Poetry is one thing that lets us sing those connections. Poetry lets us name those webs.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·