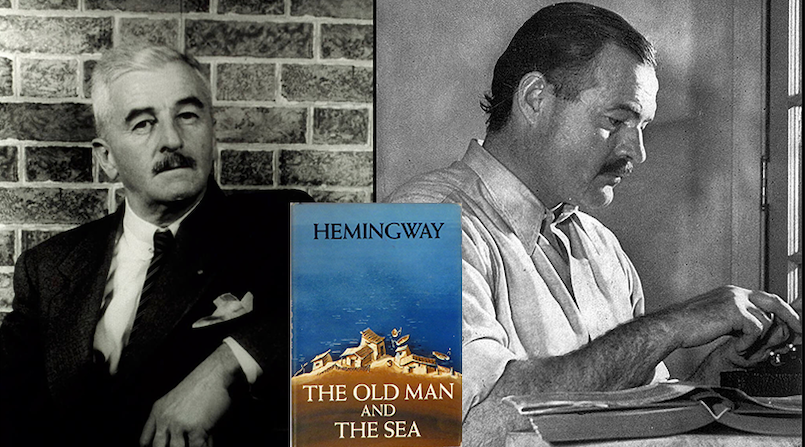

In the midcentury American literary landscape, few writers loomed as large as William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway. Both were revered internationally as well as at home, both won Nobel and Pulitzer Prizes, both wrote acclaimed short fiction alongside their novels, and both drank like fish.

Universal renown and debilitating alcoholism are where the similarities pretty much end, however. Hemingway was the quintessential minimalist, shearing his terse sentences of any and all ornamentation; Faulkner was a purveyor of experimental, elliptical, stream-of-consciousness prose. Hemingway was the bombastic veteran and war correspondent, a tornado of chest-beating machismo and unchecked ego; Faulkner was a taciturn former postmaster who despised and shunned the fame that success brought. Hemingway sent his rootless, restless surrogates to far-flung lands; Faulkner built an imagined county in which his haunted Southerners could decay.

What they did share, however, was a healthy rivalry, and though they never met in person, the two men corresponded, both in the press and in private, for years. Their most famous interaction, indeed the one that has come to epitomize their relationship in the public imagination, came when Faulkner remarked that Hemingway “has never been known to use a word that might send a reader to the dictionary,” to which Papa replied, “Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words?”

Despite what this catty exchange would have you believe, Faulkner and Hemingway were actually great admirers of each other’s work, regularly offering up (qualified) praise. Perhaps the greatest single example of this came in 1952, when Faulkner agreed to write the below single-paragraph review of The Old Man and the Sea for Washington and Lee University’s literary journal, Shenandoah.

*

His best. Time may show it to be the best single piece of any of us, I mean his and my contemporaries. This time, he discovered God, a Creator. Until now, his men and women had made themselves, shaped themselves out of their own clay; their victories and defeats were at the hands of each other, just to prove to themselves or one another how tough they could be. But this time, he wrote about pity: about something somewhere that made them all: the old man who had to catch the fish and then lose it, the fish that had to be caught and then lost, the sharks which had to rob the old man of his fish; made them all and loved them all and pitied them all. It’s all right. Praise God that whatever made and loves and pities Hemingway and me kept him from touching it any further.