Every writer lives in fear of their book being savaged by an acid-penned critic in a major publication. They wake up tangled in their bedclothes, drenched in cold sweat, seeing visions of James Wood or Dale Peck or Michiko Kakutani (uncapped red marker in hand, cackling maniacally) at the foot of their bed. Or at least they did, back in the era when one New York Times or New Republic or New Yorker review could make or break a book before it even hit the shelves. In recent times, a single glowing write-up isn’t nearly as valuable as it used to be, nor is a single savage pan as damning. There are just too many outlets, too many takes, too much information flying around social media for any one review to silence the cacophony of voices. Perhaps that’s a good thing, perhaps not.

Though the times they have a-changed, however, one maxim remains as true today as it has been for decades: do not publicly respond to a negative review of your book. You may well have some legit grievances with how a critic has chosen to interpret your work. You may wish to point out a flaw in their argument or rebut an issue they had with your storytelling or characterization. You may be frustrated that the Grey Lady chose a stuffy Maritime historian to review your swashbuckling pirate novel. But you must try to calm yourself. The damage, sadly, has already been done and the best course of action now is to go for a long, angry run in the rain, screaming profanities at the sky like Lear on the heath, and then try to forget about it; because there’s nothing you can do. There are exceptions to this rule, of course. No small number of writers have been vindicated in the letters pages and on social media having called out inaccurate, lazy, or in some cases downright prejudicial book reviews, and if you’re certain that you have an iron clad case, by all means have at it.

Before you do, though, why not take a look at the below examples of famous writers who also decided not to just shake it off.

*

The Book: Eugene Onegin by Alexandr Pushkin, Trans. by Vladimir Nabokov

The Review: Edmund Wilson (The New York Review of Books), July 15, 1965

“This production, though in certain ways valuable, is something of a disappointment; and the reviewer, though a personal friend of Mr. Nabokov—for whom he feels a warm affection sometimes chilled by exasperation—and an admirer of much of his work, does not propose to mask his disappointment. Since Mr. Nabokov is in the habit of introducing any job of this kind which he undertakes by an announcement that he is unique and incomparable and that everybody else who has attempted it is an oaf and an ignoramus, incompetent as a linguist and scholar, usually with the implication that he is also a low-class person and a ridiculous personality, Nabokov ought not to complain if the reviewer, though trying not to imitate his bad literary manners, does not hesitate to underline his weaknesses … Aside from this desire both to suffer and make suffer—so important an element in his fiction—the only characteristic Nabokov trait that one recognizes in this uneven and sometimes banal translation is the addiction to rare and unfamiliar words, which, in view of his declared intention to stick so close to the text that his version may be used as a trot, are entirely inappropriate here.”

The Response: A salty point-by-point rebuttal in the following month’s issue of the New York Review of Books.

“I fully share ‘the warm affection sometimes chilled by exasperation’ that he says he feels for me. In the 1940s, during my first decade in America, he was most kind to me in various matters, not necessarily pertaining to his profession. I have always been grateful to him for the tact he showed in refraining from reviewing any of my novels. We have had many exhilarating talks, have exchanged many frank letters. A patient confidant of his long and hopeless infatuation with the Russian language, I have always done my best to explain to him his mistakes of pronunciation, grammar, and interpretation … I suggest that Mr. Wilson’s didactic purpose is defeated by the presence of such errors (and there are many more to be listed later), as it is also by the strange tone of his article. Its mixture of pompous aplomb and peevish ignorance is certainly not conducive to a sensible discussion of Pushkin’s language and mine.”

*

The Book: The Sportswriter by Richard Ford

The Review: Alice Hoffman (The New York Times), March 23, 1986

“…it suffers from a lack of compelling action and an emphasis on Bascombe’s dry meditations that obscures and minimizes the complex domestic structure the author initially presents. Mr. Ford is a daring and intelligent novelist, but in choosing Bascombe as his narrator he has taken a risk that ultimately does not pay off. The authorial voice is so weakened that we are left only with the observations of an emotionally untrustworthy narrator. This is not to say that the author doesn’t allow us some access to Bascombe’s psyche. Certainly, his observations about a former athlete hold true for himself, for what he needs ”is to strap on a set of pads and beat the daylights out of somebody and quit worrying about theories of art.” He never trades theorizing for action. His inability to write fiction, which should illuminate his inability to connect emotionally, instead seems trivial. Even mourning is replaced by self-analysis, so that Bascombe’s lost son seems less a ghostly presence than a tiny piece of glass set in the kaleidoscope of self-scrutiny.”

The Response: Ford took one of Hoffman’s books out into the back yard, shot it, and then mailed the pieces to her.

“Well my wife shot it first,” Ford told the Guardian, “rather proudly.” “She took the book out into the back yard, and shot it. But people make such a big deal out of it—shooting a book—it’s not like I shot her.”

*

The Book: A Man in Full by Tom Wolfe

The Reviews: Norman Mailer (The New York Review of Books), December 17, 1998 / John Updike (The New Yorker), November 9, 1998

Mailer: “The book has gas and runs out of gas, fills up again, goes dry. It is a 742-page work that reads as if it is fifteen hundred pages long. This is, to a degree, a compliment, since it is very rich in material. But, given its high intentions, it is also tiresome, for it takes us down the road of too many overlong and predictable scenes. Electric at best, banal at worst—banal like a long afternoon spent watching soap operas—one picks it up each day to read another hundred pages with the sense that the book not only offers pleasure but the strain of encountering prose that disappoints as often as it titillates.

At certain points, reading the work can even be said to resemble the act of making love to a three-hundred-pound woman. Once she gets on top, it’s over. Fall in love, or be asphyxiated. So you read and you grab and you even find delight in some of these mounds of material. Yet all the while you resist—how you resist!—letting three hundred pounds take you over.”

Updike: “A Man in Full still amounts to entertainment, not literature, even literature in a modest aspirant form. Like a movie desperate to recoup its bankers’ investment, the novel tries too hard to please us.”

The Response: Wolfe hit back at both in turn (as well as John Irving, who had called Wolfe’s novels “yak” and “journalistic hyperbole described as fiction”), and collectively called his opponents “the Three Stooges.”

“I think of the three of them now—because there are now three, as Larry, Curly and Moe—it must gall them a bit that everyone, even them, is talking about me.”

*

The Book: A Multitude of Sins by Richard Ford

The Review: Colson Whitehead (The New York Times Book Review), March 3, 2002

“The characters are nearly indistinguishable. If I were an epidemiologist, I’d say that some sort of spiritual epidemic had overtaken a segment of our nation’s white middle-class professionals, and has started to afflict white upper-middle-class professionals. These characters could use some good advice, and if they had friends, they might be able to ask for it, but they don’t have friends. Sometimes the men are named Roger or Tom, sometimes the women are named Nancy or Frances. If they have children, we rarely see them. Some of them meet in fancy hotel rooms, others prefer out-of-the-way motels. Whatever the specifics, adulterous or not, they bide their time for opportunities to offer portentous declarations about their predicaments like: ‘Other people affect you. It’s really no more complicated than that’ and ‘I am sure now that all of this had to do with my impending failures.’ These declarations will strike you as plain-spoken and hard-earned wisdom, or easy banalities, depending on your mood or level of generosity.”

The Response: Ford approached Whitehead at a literary party, told the future National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize winner to grow up, and then spat in his face.

“I’ve waited two years for this,” he said. “You spat on my book.” Then he spat on Whitehead. Reporting this to Deborah Schoenman, Whitehead said, “We had a few heated words—he said, ‘You’re a kid, you should grow up,’ which coming from him was a bit funny—and then he stalked off. This wasn’t the first time some old coot had drooled on me, and it probably won’t be the last. But I would like to warn the many other people who panned the book that they might want to get a rain poncho, in case of inclement Ford.”

*

The Book: The Black Veil: A Memoir with Digressions by Rick Moody

The Review: Dale Peck (The New Republic), July 1, 2002

“Rick Moody is the worst writer of his generation. I apologize for the abruptness of this declaration, its lack of nuance, of any meaning besides the intuitive; but as I made my way through Moody’s oeuvre during the past few months I was unable to come up with any other starting point for a consideration of his accomplishment. Or, more accurately, every other starting point that I tried felt disingenuous, nothing more than a way of setting Moody up in order to knock him down. One of those starting points was this: “Rick Moody is a lot of things, but he is not actually dumb.” This was an attempt at charity, and though I still think that it’s true enough, I don’t think that it matters; at any rate, his intelligence does not make up for the badness of his books.”

The Response: A good-natured publicity stunt in which Moody hit Peck in the face with a pie at a charity fundraiser.

*

The Book: Yellow Dog by Martin Amis

The Review: Tibor Fischer (The Telegraph), August 4, 2003

“I won’t tell you anything about the contents of Yellow Dog, but what I will tell you is that it’s terrible … one of Amis’s weaknesses is that he isn’t content to be a good writer, he wants to be profound; the drawback to profundity is that it’s like being funny, either you are or you aren’t, straining doesn’t help. This ache for gravitas has led to much of Amis’s weaker work … Yellow Dog isn’t bad as in not very good or slightly disappointing. It’s not-knowing-where-to-look bad. I was reading my copy on the Tube and I was terrified someone would look over my shoulder (not only because of the embargo, but because someone might think I was enjoying what was on the page). It’s like your favourite uncle being caught in a school playground, masturbating.”

The Response: Succinct, but memorable.

“Tibor Fischer is a creep and a wretch. Oh yeah: and a fat-arse.”

*

The Book: Shalimar the Clown by Salman Rushdie

The Review: John Updike (The New Yorker), September 5, 2005

“Why, oh why, did Salman Rushdie, in his new novel, call one of his major characters Maximilian Ophuls? Max Ophuls is a highly distinctive name, well known to movie lovers as that of a German-born actor and stage director who, beginning in 1930, directed films in Germany, France, Russia, Italy, the Netherlands, and, after 1946, the United States. Readers of this review will be spared, as the reviewer was not, the maddening exercise of trying to overlay Rushdie’s Ophuls with the historical one … Why has Rushdie attached a gaudy celebrity name to a different sort of celebrity, preventing the Ambassador from coming into sharp, living focus on his own? It is partly, perhaps, characteristic Rushdiean overflow. His novels pour by in a sparkling, voracious onrush, each wave topped with foam, each paragraph luxurious and delicious, but the net effect perilously close to stultification.”

The Response: A scathing aside in a Guardian interview with James Campbell.

“A name is just a name. ‘Why, oh why … ?’ Well, why not? Somewhere in Las Vegas there’s probably a male prostitute called ‘John Updike.’ The thing that disappointed me most about Updike is that he did not say in that review that he had just completed a novel about terrorism. He had to sweep me out of the way in order to make room for himself. I don’t subscribe to the very predominantly English admiration of Updike. If you take away Rabbit is Rich and Rabbit at Rest, and some of the short stories, there’s a lot of … slightly … garbage. Think of The Coup! The new one [Terrorist] is beyond awful. He should stay in his parochial neighbourhood and write about wife-swapping, because it’s what he can do.”

*

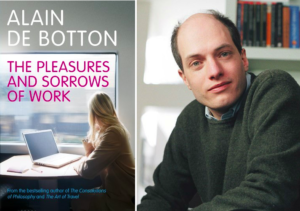

The Book: The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work by Alain de Botton

The Review: Caleb Crain (The New York Times Book Review), June 24, 2009

“Everyone has a price in theory; a worker is someone who has agreed to a number. He is exposed as someone under constraint, like a prisoner in a stockade. To mock him for being less than perfectly free in his thoughts and actions is easy. Unfortunately, the British essayist Alain de Botton indulges in this kind of mockery in his new book … If de Botton were genuinely concerned that work today lacks meaning, surely here was an opportunity to ask questions. But is he worried that work today lacks meaning? Or just that some work means more to other people than he thinks it should? … it’s an abdication of journalistic responsibility. If a disinterested writer won’t try to distinguish the efficacy of an endeavor from its trappings, who will?”

The Response: An enraged comment on the critic’s personal blog:

“Caleb, you make it sound on your blog that your review is somehow a sane and fair assessment. In my eyes, and all those who have read it with anything like impartiality, it is a review driven by an almost manic desire to bad-mouth and perversely depreciate anything of value. The accusations you level at me are simply extraordinary. I genuinely hope that you will find yourself on the receiving end of such a daft review some time very soon – so that you can grow up and start to take some responsibility for your work as a reviewer. You have now killed my book in the United States, nothing short of that. So that’s two years of work down the drain in one miserable 900 word review. You present yourself as ‘nice’ in this blog (so much talk about your boyfriend, the dog etc). It’s only fair for your readers (nice people like Joe Linker and trusting souls like PAB) to get a whiff that the truth may be more complex. I will hate you till the day I die and wish you nothing but ill will in every career move you make. I will be watching with interest and schadenfreude.”

*

The Book: The Story Sisters by Alice Hoffman

The Review: Roberta Silman (The Boston Globe), June 28, 2009

“…this new novel lacks the spark of the earlier work. Its vision, characters, and even the prose seem tired. Too much of it is told rather than shown, and the story itself is a strange combination of a coming-of-age novel set on Long Island and a brutal story of the consequences of a childhood trauma that leads into a fateful descent into drugs for the main character, Elv, the eldest sister … Neither Hoffman nor her characters seem able to acknowledge the havoc they have created. Only Claire is given a chance to grow, and although Elv does bear a child and reform, she never really matures. Nor do we feel a sense of intimacy with her, the kind of relationship between a main character and a reader that marks a really fine novel.”

The Response: A series of angry Twitter posts which included Silman’s phone number, email address, and an invitation for fans to “Tell her what u think of snarky critics.”

“Roberta Silman in The Boston Globe is a moron … How do some people get to review books? And give the plot away.”