These 10 fiction and nonfiction recommendations play in the sandbox of political fantasy and explore the limits of the comic book format—just like Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ influential graphic novel did over thirty years ago.

“Not a movie, not a novel. A comic book.” Alan Moore is nothing if not consistent. In the 14 years since Entertainment Weekly quoted the comic creator’s definitive statement on his most famous work, Watchmen, his cantankerousness toward adaptations or reimaginings of his work has not wavered. He might have even put a curse on Damon Lindelof, the TV showrunner of its shiny new HBO series of the same name. Still, whether or not Moore likes this new Watchmen show (an extrapolation of the universe rather than a straight adaptation), it’s here, and along with it a renewed interest in the book he created with illustrator Dave Gibbons and colorist John Higgins. When you’re done reading the original comic, here’s what else you should pick up.

Transmetropolitan by Warren Ellis and Darick Robertson

While the no-quarter-given superhero book The Authority might feel like the closest Watchmen analogue written by Warren Ellis, Transmetropolitan, which he created with illustrator Darick Robertson, holds up a lot better more than 15 years after the start of the Iraq War. Transmetropolitan‘s hero is Spider Jerusalem, a chain-smoking gonzo reporter in the near future who lives for the truth and rails against the corrupt engines of society surrounding him. His enemies are liars and criminals who are closer to the supervillains we know exist in the real world, and his F-bomb-infused dialogue is pretty spectacular. (“I swear you’d stick it in mud if you thought it’d wriggle.”)

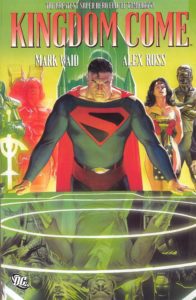

Kingdom Come by Mark Waid and Alex Ross

Though Watchmen is published by DC Comics, it doesn’t feature the likes of Superman, Batman, or Wonder Woman, but Kingdom Come does. In its future, as with Watchmen‘s, superheroes have lost their way and the public has abandoned them in favor of heroes who are fine with killing bad guys. The story by veteran DC writer Mark Waid is informed by decades of superhero mythology, and unlike most comics, Kingdom Come is painted in gouache by illustrator Alex Ross. The result is pages filled with action and symbolic meaning that read like magnificent superheroic frescoes, as if you had tasked a Renaissance artist with the coda to a half-century of DC history. Mercifully, Kingdom Come ends on a more hopeful note.

Planetary by Warren Ellis and John Cassaday

Planetary‘s engrossing plot and infectious characters undoubtedly felt underserved by its inconsistent publishing schedule (the last issue took three years longer than expected to finally hit the shelves), but in the end the wait was worth it. The book bills its heroes as “Archaelogists of the Impossible”—investigators of extranormal phenomena ripped from the pages of genre fiction. Kaiju monsters, Sherlock Holmes, the Fantastic Four, and a lot more cultural touchpoints are parodied or refashioned in its pages, just like how Watchmen refashioned the Charlton Comics characters (and Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen refashioned pulp heroes) to tell its story. Unlike Watchmen, Planetary is a love letter to its influences more than it is a deconstruction of them. That doesn’t make it any less delicious to consume, especially with John Cassaday’s clean lines guiding you through Ellis’s batshit plot.

Black Panther by Christopher Priest and various artists

Before Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther, there was really Christopher Priest’s Black Panther and all the rest. Plenty of talented artists and writers have gone at the character, but none have been as influential in infusing politics into his mythology. Unlike previous writers who thought of him first as a superhero, “[Priest] thought that Black Panther was a king,” fellow Black Panther writer Ta-Nehisi Coates once explained. Throughout the influential 62-issue run between 1998 and 2003, Priest bounced King T’Challa around the world solving crises, looking fly as hell, and squaring off against complex villains like his own brother, always with his political standing as a head of state in mind. Like Watchmen, its questions and answers as to what power means were complicated and a lot of fun to read.

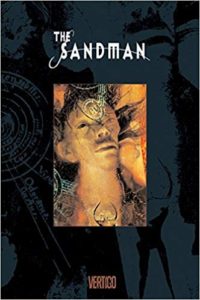

Sandman by Neil Gaiman and various artists

Something a lot of people forget about Neil Gaiman is that he helped Alan Moore out on Watchmen in the ’80s, sending the fellow writer quotes and other material to help him expand the book’s much-footnoted mythology. Gaiman even got an acknowledgement in the front of the collected volume. Sandman‘s world is even bigger, packed with references to heaven, hell, Greek myth, and Shakespeare. Gaiman’s protagonist Morpheus, lord of dreams, anchors the book’s fantastical, unforgettable stories, and Sandman‘s status as a legendary work in its own right has endured since 1991, when the series won a World Fantasy Award—an upset that prompted its organizing body to subsequently change the rules so no comic could win the prize again.

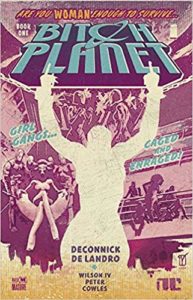

Bitch Planet by Kelly Sue DeConnick and Valentine De Landro

Like Watchmen, this dystopian tale used the trappings of genre—in this case, “women in prison” exploitation films—to offer a mature and often brash commentary on the modern world’s misogyny. Bitch Planet is the feminist story of what so-called “non-compliant” women do when pushed to the brink by the villainous “Council of Fathers.” The gorgeous art from Valentine De Landro and complex satire from DeConnick’s writing make it a must-read, and the issues come with self-referential, fake, in-universe ads, the same way Watchmen used prose written by its characters to enrich its story.

Understanding Comics by Scott McCloud and Making Comics by Lynda Barry

Lynda Barry won a damn MacArthur Fellowship within two months of her book Making Comics‘s release, and Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics has served as the medium’s most important textbook for the past three decades. They’re both terrifically artful instructional manuals for 1) what comics can do that no other medium can’t, and 2) how comic artists can make the best use of that. In the same way that Moore and Gibbons set out to show the world what only comics as a medium could do, so do these books. Understanding, for the most part, is more analytical, outlining in illustrations how sequential art carries readers across the page and why we often identify with simplified figures of faces more than we do with realistic reproductions. Making feels more personal, structured like a composition notebook packed with tips, pencil drawings, sketches, and ideas for creating art. Both are essential.

Marvelman (aka Miracleman) by Alan Moore and Alan Davis

Marvelman today is available in trade paperbacks under the banner Miracleman and credited to “The Original Writer”—who is Alan Moore—due to a series of legal issues too complex to get into, but the ’80s run functioned as a prologue to much of his later work. Marvelman wasn’t shy about putting babies in peril, deconstructing its superhero as the locus of that peril, and using graphically realistic art to convey its grittiness. It was Watchmen before Watchmen, and though Moore took his name off the work, it’s no less compelling to read nowadays.

Watching the Watchmen by Dave Gibbons and Magic Words: The Extraordinary Life of Alan Moore by Lance Parkin

If you want to read the Watchmen‘s creators’ respective takes on the book straight from the horse’s mouths, look no further than this pair of histories. Historian Lance Parkin’s Magic Words, uncontroversially, calls Dave Gibbons’ Watching the Watchmen “the definitive account of the development of the series,” while Alan Moore cover-blurbed Parkin’s biography of him as belonging “on the bookshelf of any halfway decent criminal profiler.” They both get into the creation, rights battles, and many, many differences of opinion around who is owed what for Watchmen, but they also include quotes about its cultural footprint. Here’s one from Moore from 2002, on page 185 of Magic Words: “Get over Watchmen, get over the 1980s. It doesn’t have to be depressing miserable grimness from now until the end of time. It was only a bloody comic.”

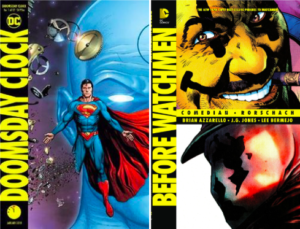

Doomsday Clock and Before Watchmen by various creative teams

Most may see these comics as a cynical corporate cash-in—and, uh, they totally are—but if you love the characters in Watchmen and want to read more of their adventures, there’s really just the original book by Moore and Gibbons… and these. Of the Before Watchmen run, the miniseries produced by the late, great writer/illustrator Darwyn Cooke, Before Watchmen: Minutemen and Before Watchmen: Silk Spectre (co-written by Amanda Conner and illustrated by her too), are probably the best of that set of stories, which serve as prequels to the main series. Doomsday Clock, currently in publication from writer Geoff Johns and penciller Gary Frank, is a sequel to the series that also functions as the climactic chapter in DC Comics’s years-long “Rebirth” effort, and brings together the characters in DC’s mainline chronology like Superman in direct conflict with Watchmen‘s. Neither of these comic runs affect the original series or its events in any meaningful way, but they do telegraph what we expect for this intellectual property in the future: more Watchmen comics, whether Alan Moore wants them or not.