Sometimes we have the absolute certainty there’s something inside us that’s so hideous and monstrous that if we ever search it out we won’t be able to stand looking at it.

*

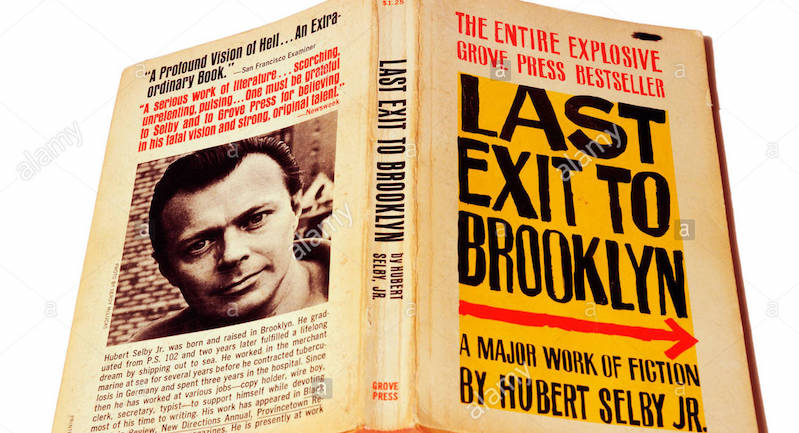

“It is inconceivable that anyone will read Hubert Selby Jr.’s Last Exit to Brooklyn twice over. Readers who don’t have copperlined stomachs will have trouble getting through it even once. It is rude, powerful gut-writing. There may be protest in the background, even a buried point of view, but it is submerged between waves of shockingly bestial detail. Most of the narrative elements in the stories cannot be mentioned in what one still thinks of as decent company; and as for consecutive thought and critical perspective, they are as much out of place as they would be in the presence of a skunk. The book’s major effort is clearly to nauseate—and I am not saying this to attack it. On the contrary, it is a terribly effective book, not simply because its details are thickly packed, admirably selected, and arranged with stark power to achieve its chosen effect, but also because it denies one all perspective of the apish world it presents. It is written to be held close to the nose, and read over a rising gorge.

“When people are beaten up, they are not only kicked to a foaming, puking, bloody pulp, but the only reaction in evidence is someone’s gloating satisfaction. When a prostitute is literally abused to death, children gather round to watch, to add their own quota of broomsticks and filth, and finally to wander away, bored. Of course, merely by the act of being a book, and appealing to that small percentage of the public that reads books, the stories can count on a reaction of protest from their readers. Or can they? A good deal of prurient fantasy seems to pass in print, these days, under the mask of rigorous honesty. Those completely frank, scientific discussions of sexual technique which draw full-page ads in The New York Times and somehow manage to sell for twice as much as any other book of equivalent size are a case in point. Are they read by or sold to scientists or potential scientists? Somehow it seems doubtful.

“I have no reason to doubt that the author of Last Exit to Brooklyn is, as the dust-jacket assures me, a fierce moralist; so was Swift, who also wrote some fairly revolting pornography. (Somehow it seems comfortable to have it both ways: free indulgence in filth, salved with the reflection that it shows what a clean-minded fellow one is.) But public morals, if any, aren’t the issue, simply this book’s tendency to undermine an old and deteriorating concept of a book. In the old days, we had a distinction between pornography (kinetic in effect, either emetic or aphrodisiac) and literature (static in effect, aiming at esthetic distance). As that distinction goes under (and already it seems nineteenth-century), some other is going to be needed between, let us call it, impact-writing and writing for reflection. Grant that it won’t be clear-cut that many books will make both appeals, yet it will point up a difference in mode and perhaps in standards of judgment, as well as a trend whose term it is impossible to foresee.

“No categorical judgment is intended between the two species, though one can hardly help seeing shock as a limited response to a book. Just for that reason it may be useful to put the shock-books together and perhaps try to develop some shock-experts who will be able to distinguish Mere Shock from Shock for the Sake of Something Larger. For so important an issue, this decision seems often to be grounded on evanescent shadings of evidence (cases of Baudelaire and de Sade); perhaps a second book, if anyone can bear it, will tell us more about Hubert Selby, Jr. At any rate, for the moment, Mr. Selby has written a sickeningly good book, from which I am happy to have escaped.”

–Robert M. Adams, The New York Review of Books, December 3, 1964