I too am not a bit tamed—I too am untranslatable.

I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world.

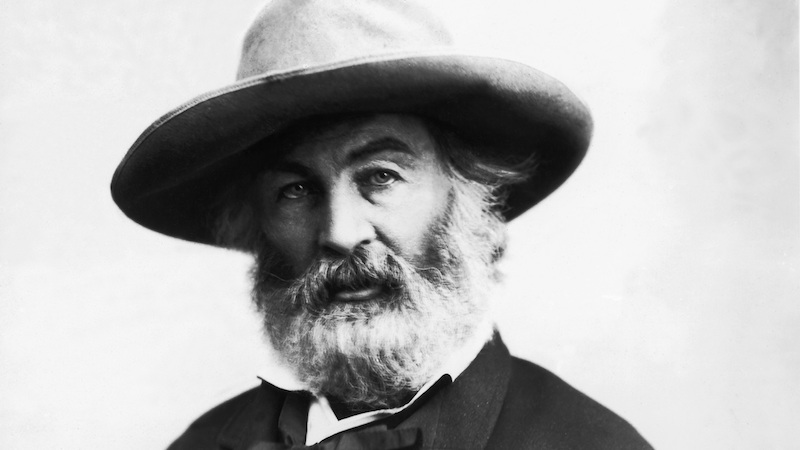

“We had ceased, we imagined, to be surprised at anything that America could produce. We had become stoically indifferent to her Woolly Horses, her Mermaids, her Sea Serpents, her Barnums, and her Fanny Ferns; but the last monstrous importation from Brooklyn, New York, has scattered our indifference to the winds. Here is a thin quarto volume without an author’s name on the title-page; but to atone for which we have a portrait engraved on steel of the notorious individual who is the poet presumptive. This portrait expresses all the features of the hard democrat, and none of the flexile delicacy of the civilised poet. The damaged hat, the rough beard, the naked throat, the shirt exposed to the waist, are each and all presented to show that the man to whom those articles belong scorns the delicate arts of civilisation. The man is the true impersonation of his book—rough, uncouth, vulgar. It was by the merest accident that we discovered the name of this erratic and newest wonder; but at page 29 we find that he is—

Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs, a Kosmos,

Disorderly, fleshly, and sensual.

The words ‘an American’ are a surplusage, ‘one of the roughs’ too painfully apparent; but what is intended to be conveyed by ‘a Kosmos’ we cannot tell, unless it means a man who thinks that the fine essence of poetry consists in writing a book which an American reviewer is compelled to declare is ‘not to be read aloud to a mixed audience.’ We should have passed over this book, Leaves of Grass, with indignant contempt, had not some few Transatlantic critics attempted to ‘fix’ this Walt Whitman as the poet who shall give a new and independent literature to America—who shall form a race of poets as Banquo’s issue formed a line of kings. Is it possible that the most prudish nation in the world will adopt a poet whose indecencies stink in the nostrils? We hope not; and yet there is a probability, and we will show why, that this Walt Whitman will not meet with the stern rebuke which he so richly deserves. America has felt, oftener perhaps than we have declared, that she has no national poet—that each one of her children of song has relied too much on European inspiration, and clung too fervently to the old conventionalities. It is therefore not unlikely that she may believe in the dawn of a thoroughly original literature, now there has arisen a man who scorns the Hellenic deities, who has no belief in, perhaps because he has no knowledge of, Homer and Shakspere; who relies on his own rugged nature, and trusts to his own rugged language, being himself what he shows in his poems.

“Once transfix him as the genesis of a new era, and the manner of the man may be forgiven or forgotten. But what claim has this Walt Whitman to be thus considered, or to be considered a poet at all? We grant freely enough that he has a strong relish for nature and freedom, just as an animal has; nay, further, that his crude mind is capable of appreciating some of nature’s beauties; but it by no means follows that, because nature is excellent, therefore art is contemptible. Walt Whitman is as unacquainted with art as a hog is with mathematics. His poems—we must call them so for convenience—twelve in number, are innocent of rhythm, and resemble nothing so much as the war-cry of the Red Indians. Indeed, Walt Whitman has had near and ample opportunities of studying the vociferations of a few amiable savages. Or rather perhaps, this Walt Whitman reminds us of Caliban flinging down his logs, and setting himself to write a poem. In fact Caliban, and not Walt Whitman, might have written this:

I too am not a bit tamed—I too am untranslatable.

I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world.

Is this man with the ‘barbaric yawp’ to push Longfellow into the shade, and he meanwhile to stand and ‘make mouths’ at the sun? The chance of this might be formidable were it not ridiculous. That object or that act which most develops the ridiculous element carries in its bosom the seeds of decay, and is wholly powerless to trample out of God’s universe one spark of the beautiful. We do not, then, fear this Walt Whitman, who gives us slang in the place of melody, and rowdyism in the place of regularity. The depth of his indecencies will be the grave of his fame, or ought to be if all proper feeling is not extinct. The very nature of this man’s compositions excludes us from proving by extracts the truth of our remarks; but we, who are not prudish, emphatically declare that the man who wrote page 79 of the Leaves of Grass deserves nothing so richly as the public executioner’s whip. Walt Whitman libels the highest type of humanity, and calls his free speech the true utterance of a man: we, who may have been misdirected by civilisation, call it the expression of a beast.”

“We will neither weary nor insult our readers with more extracts from this notable book. Emerson has praised it, and called it the ‘most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom America has yet contributed.’ Because Emerson has grasped substantial fame, he can afford to be generous; but Emerson’s generosity must not be mistaken for justice. If this work is really a work of genius—if the principles of those poems, their free language, their amazing and audacious egotism, their animal vigour, be real poetry and the divinest evidence of the true poet—then our studies have been in vain, and vainer still the homage which we have paid the monarchs of Saxon intellect, Shakspere, and Milton, and Byron. This Walt Whitman holds that his claim to be a poet lies in his robust and rude health. He is, in fact, as he declares, ‘the poet of the body.’ Adopt this theory, and Walt Whitman is a Titan; Shelley and Keats the merest pigmies. If we had commenced a notice of Leaves of Grass in anger, we could not but dismiss it in grief, for its author, we have just discovered, is conscious of his affliction. He says, at page 33,

I am given up by traitors;

I talk wildly, I am mad.

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.