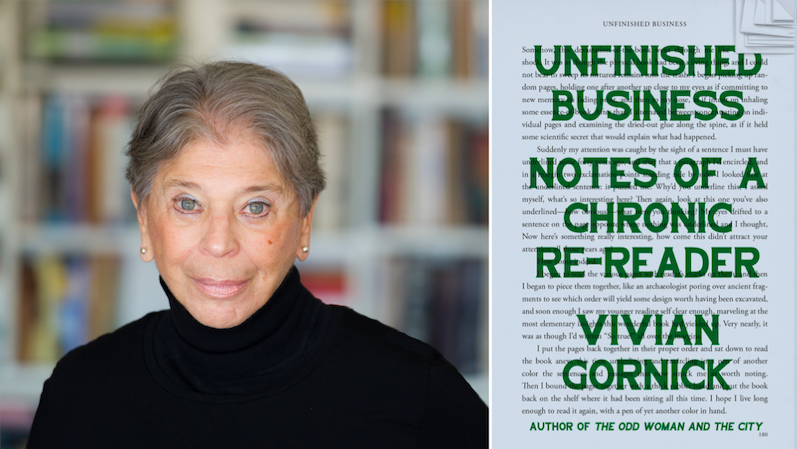

Vivian Gornick’s Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Rereader, is published this month. She shares five books that made a difference in her writing life.

Little Virtues by Natalia Ginzburg

The first book taught me how to write a personal essay.

Jane Ciabattari: In Unfinished Business you write of reading Ginzburg’s essay “My Vocation”: “Bit by bit it comes clear that the essay itself, the one Ginzburg has written and we are reading, is a miniature bildungsroman where in the author is teaching herself how to grow up and take her place in the world as a human being who is a writer; that is the story.” Can you mention early essays you wrote after reading Ginzburg?

Vivian Gornick: Most of the essays in my collection Approaching Eye Level were written in the wake of Ginzburg’s eye-opening “My Vocation.” With each piece in that book I knew consciously that I was struggling to make some large sense of the subject in hand. That is, I knew by then that the personal essay, as well as making use of a particular piece of experience, must dive deep enough to achieve metaphorical meaning. That is what Ginzburg’s essays taught me—and to this day go on teaching me. In Approaching Eye Level, the piece that gave me the most trouble was the reminiscence of my time working as a waitress in the Catskill Mountains. Whatever it was that I was trying to get at in that piece, it refused to come clear—it still feels unclear. I knew, all the time I was working on it, that it needed a Ginzburg rather than a Gornick to bring it to some satisfying point of arrival. If I read it today, it still feels like I’m touching a sore spot..

Father and Son by Edmund Gosse

The second book taught me the meaning of “being alone with yourself.”

JC: Gosse’s memoir describes his temperamental differences from his father—and his shift from following his father’s devout fundamentalism to his own choice to move to London and grow “older and more independent in mind” and take “a human being’s privilege to fashion his inner life for himself.” Did you experience similar differences of temperament with your parent(s)?

VG: Of course. Gosse’s memoir is one of the most brilliant illustrations of how a person takes seriously the task of coming to conscious understanding of who and what one is going to be. I first read the book in early adulthood, and instantly, it made me realize the meaning of every struggle of my own to separate the value I attached to my actual experience as opposed to the value I attached to the second-hand experience I was receiving from my parents (mostly my mother). It took a fair amount of living to realize that my mother’s insistence that “love is the most important thing in a woman’s life” was not going to be the guiding influence in mine. And every time I re-read Father and Son I understood better that it was my obligation to pay attention to the difference between Mama and me on this score.

The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton

The third book showed me how to make use of the divided self in literature.

JC: Wharton’s Lily Bart is a character who both follows her inner drive and behaves in ways that reinforce the social mores against which she wishes to rebel. She is riddled with mixed messages, conflicts, ambivalence. In “The End of the Novel of Love,” you write, “Lily Bart…is a woman divided against herself in a world of social rigidities that are not negotiable. Lily can neither face the decision to marry a bourgeois nor can she bear excommunication from the only world she knows. She…sabotage[s] herself time after time until, finally, all that is left to her is a compromised marriage to an upstart Jew or suicide. She chooses suicide.” Does Lily reflect the limits of her times, with resistance her most courageous option?

VG: Yes, Lily is certainly a product of her time (one in which the social constraints on a woman who does not marry are incredibly severe)….but Wharton’s acute intelligence makes use of those constraints to let the reader feel that famous shock of recognition: the one in which we realize that whatever the time or circumstance, whoever the protagonist, our fear of knowing ourselves is greater than the need to live an integrated life….and this fear is at the heart of most serious literary concerns. That is certainly how I read The House of Mirth.

The Odd Women by George Gissing

The fourth book showed me how to make a metaphor out of feminist politics.

JC: This novel spoke to you, it’s clear. You took the title of Gissing’s novel, about a “woman who just can’t make her peace with being in the world as the world is,” for your 2015 memoir The Odd Woman and the City. And in a 2015 essay in Dissent you wrote of The Odd Women, “In this novel—published in 1893—I could see and hear the characters as if they were women and men of my own acquaintance. I knew intimately what was tearing these people apart. What’s more, I recognized myself as one of the ‘odd’ women. Every fifty years from the time of the French Revolution, feminists had been described as ‘new’ women, ‘free’ women, ‘liberated’ women—but Gissing had gotten it just right. We were the ‘odd’ women.” What makes Gissing’s novel strike you as so authentic?

VG: This, for me, is one of the great feminist novels of the 19th century (nearly all of which, painful paradox, were written by men). In The Odd Women the major protagonists—two who think of themselves as the New Woman and the New Man— spar intellectually, and fall in love through the marvelously extended exchange Gissing provides for them. Then the psychologically astute author of their being deepens the situation by making the gap between practice and theory kick in: the fear of social transgression proves stronger than the yearning to live freely and honestly, as both have declared they wish to live, without benefit of marriage. The failure destroys them. It was that gap between practice and theory that Gissing understood so perfectly, that compelled me, made me see myself and most of my generation in his novel rather than in many others, written by people with greater literary gifts (Wharton, James, Meredith) but not greater acuity.

Portrait of Zelide by Geoffrey Scott

The fifth book showed me how to find an organizing principle for a short biography.

JC: And what was that organizing principle?

VG: Isabelle Van Tuyll (known as Zelide), a Dutch noblewoman of the 18th century, was a woman of wealth and intelligence, a worldly spirit, and literary giftedness. Throughout her youth she was a figure on the European social scene, presented repeatedly at court in hopes of gaining a husband. But no one would do. She wanted to be in love and to be in love with an equal, but this proved impossible. Either she was not attracted to the current suitor or he was not attracted to her Most often, it was she who was doing the refusing. Her superior intelligence was a drawback. Years passed, and she grew gravely silent. She stopped traveling. In the goodness of time—by now she’s no longer young—she married her brother’s mathematics tutor, a man of dry temperament and limited expressiveness, and went to live in a remote castle in Switzerland where she pined away for the rest of her long days—nonetheless, conducting a vast correspondence with many intellectually accomplished men. It was these letters that made Geoffrey Scott determine on writing about Zelide. Taking Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians as his model, Scott decided to achieve a take on Zelide that would provide him with an angle of vision that would serve as an organizing principle. He sat down to read her as none before had read her and what flashed on him was not her “situation” but the neurotic restlessness with which she rejected suitor after suitor when any number of them would have done. He saw, then, the princess on the pea in her—and felt a great sympathy for her. That sympathy “organized” him. This was a book that I read at the right time in my working life: it gave me the meaning of an organizing principle that has stood me in great stead ever since.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·