A man is never such an egotist as at moments of spiritual ecstasy.

At such times it seems to him that there is nothing on earth more splendid and interesting than himself.

*

“It is pleasant to welcome Tolstoy’s The Cossacks and other tales of the Caucasus to the World Classics. ‘The greatest of Russia’s writers,’ say Mr. and Mrs. Maude in their introduction. And when we read or re-read these stories, how can we deny Tolstoy’s right to the title? Of late years both Dostoevsky and Tchekov have become famous in England, so that there has certainly been less discussion, and perhaps less reading of Tolstoy himself. Coming back to him after an interval the shock of his genius seems to us quite surprising; in his own line it is hard to imagine that he can ever be surpassed. For an English reader proud of the fiction of this country there is even something humiliating in the comparison between such a story as The Cossacks, published in 1863, and the novels which were being written at about the same time in England. As the lovable immature work of children compared with the work of grown men they appear to us; and it is still more strange to consider that, while much of Thackeray and Dickens seems to us far away and obsolete, this story of Tolstoy’s reads as if it had been written a month or two ago.

“It is as a matter of fact an early work, written for the most part some years before it was published, and preceding both the great novels. He gathered the materials when he was in the Caucasus for two years as a cadet, and the chief character is the same whom we meet so often in the later books—the unmistakable Tolstoy. As Olenin he is a young man who has run into debt and leaves Moscow with a view to saving a little money and seeing a fresh side of life. In Moscow he has had many experiences, but he has always said to himself both of love and of other things, ‘That’s not it, that’s not it.’ The story—and like most of Tolstoy’s stories it has no intricacy of plot—is the story of the devolopment of this young man’s mind and character in a Cossack village. He lives alone in a hut; observes the beauty of the Cossack girl Maryanka, but scarcely speaks to her, and spends most of his time with Daddy Eroshka in shooting pheasants and talking about sport. At length he comes to know the girl and asks her to marry him, to which she seems inclined to consent; but at that very moment the soldier to whom she is engaged is wounded, and she refuses to have anything more to do with Olenin. He therefore gets himself put upon the staff and leaves the district. When he has said goodbye to them all, he turns to look back. ‘Daddy Eroshka was talking to Maryanka, evidently about his own affairs, and neither the old man nor the girl looked at Olenin.’ Nothing is finished; nothing is tidied up; life merely goes on.

“But what a life ! Perhaps it is the richness of Tolstoy’s genius that strikes us most in this story, short though it is. Nothing seems to escape him. The wonderful eye observes everything; the blue or the red of a child’s frock; the way a horse shifts its tail; the action of a man trying to put his hands into pockets that have been sown up; every gesture seems to be received by him automatically, and at once referred by his brain to some cause which reveals the most carefully hidden secrets of human nature. We feel that we know his characters both by the way they choke and snooze and by the way they feel about love and immortality and the most subtle questions of conduct. In the present selection of stories, all the work of youth and all laid in a wild country far from town civilization, he gives freer play than in the novels to his extraordinary keenness of physical sensation. We seem actually able to see the mountains, the young soldiers, the grapes, the Cossack girls, to feel the firmness of their substance, and to see the bright colours with which the sun and the cold air have painted them. Nowhere perhaps has he written with greater zest of the excitement of sport and of the beauty of fine horses; nowhere has he made us feel more acutely how fiercely desirable the world appears to the senses of a strong young man.

…

“Tolstoy seems able to read the minds of different people as certainly as we count the buttons on their coats; but this feat never satisfies him; the knowledge is always passed through the brain of some Olcuin or Pierre or Levin, who attempts to guess a further and more difficult riddle—the riddle which Tolstoy was still asking himself, we may be sure, when he died. And the fact that Tolstoy is thus seeking, that there is always in the centre of his stories some rather lonely figure to whom the surrounding world is never quite satisfactory, makes even his short stories entirely unlike other short stories. They do not shut with a snap like the stories of Maupassant and Mérimée. They go on indefinitely. It is by their continuous vein of thought that we remember them, rather than by any incident.

…

“And thus we end by thinking again of the unlikeness between ourselves and the Russians; and by envying them that extraordinary union of extreme simplicity combined with the utmost subtlety which seems to mark both the educated Russian and the peasant equally. They do not rival as in the comedy of manners, but after leading Tolstoy we always feel that we could sacrifice our skill in that direction for something of the profound psychology and superb sincerity of the Russian writers.”

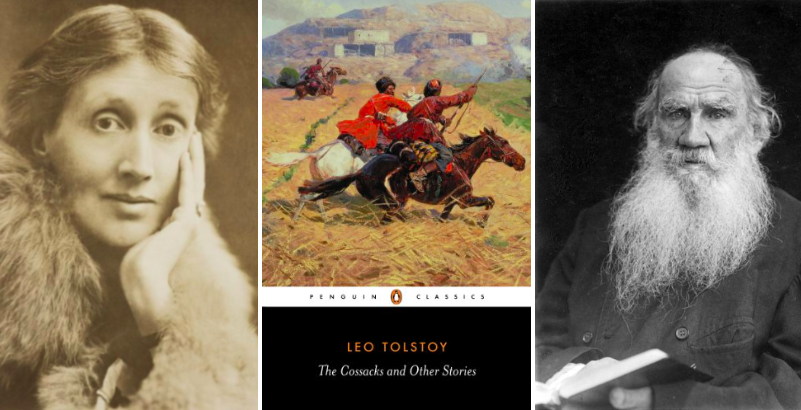

–Virginia Woolf, The Times Literary Supplement, February 1, 1917

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.