“What did God do before he created the universe?”

*

“Stephen Hawking opens his new book with a marvelous old anecdote. A famous astronomer, after a lecture, was told by an elderly lady, who was perhaps under the influence of Hinduism, that his cosmology was all wrong. The world, she said, rests on the back of a giant tortoise. When the astronomer asked what the tortoise stands on, she replied: ‘You’re very clever, young man, very clever. But it’s turtles all the way down.’

Most people, Hawking writes, would find this cosmology ridiculous, but if we take the turtles as symbols of more and more fundamental laws, the tower is not so absurd. There are two ways to view it. Either a single turtle is at the bottom, standing on nothing, or it’s turtles all the way down. Both views are held by leading physicists.

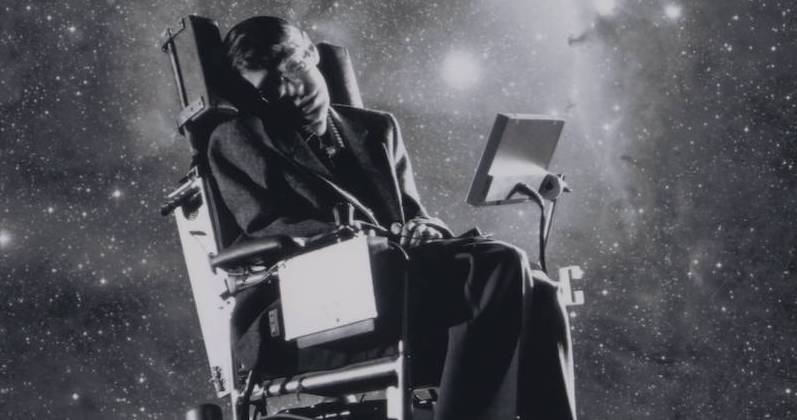

“Hawking, age forty-four, is the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge University, a chair held by Isaac Newton and Paul Dirac. Few living physicists could occupy this chair more deservedly, even though, as many by now know, Hawking has for two decades been confined to a wheelchair. He is already a legend, not just because of his brilliant contributions to theoretical physics, but also for his courage, optimism, and humor in the face of a crippling illness. Lou Gehrig’s disease may be gnawing away at his body, but it has left his mind intact. Hawking actually sees himself as fortunate. He has chosen a profession in which he can work entirely inside his head, and his disability has freed him from numerous academic chores.

A tracheostomy made necessary by a pneumonia attack in 1985 has silenced his voice. He speaks by way of a computer and speech synthesizer attached to his wheelchair. Because the synthesizer was made in California, he apologizes to strangers for his American accent. He has a devoted wife and three children. He has visited the United States some thirty times, Moscow seven times, and flown around the world. At a Chicago discotheque he once wheeled onto the floor and spun his chair in time to the music.

A Brief History of Time is Hawking’s first popularly written book. Warned that every equation would cut sales in half, he has left out all formulas except Einstein’s famous E = mc2, which he hopes will not frighten half his readers. Hawking’s prose is as informal and clear as his topics are profound.

“Before describing his new model of the universe, Hawking provides an artfully condensed overview of relativity theory and quantum mechanics. In Newton’s cosmology, motion is ‘absolute’ in the sense that it can be measured relative to a fixed, motionless space that nineteenth-century physicists called the ‘stagnant ether.’ Newton’s time is also absolute in the sense that one unvarying time pervades the universe. Einstein abandoned both notions. Space and time were fused into a single structure. Light became the only nonrelative motion, its velocity impossible to exceed, and never changing regardless of an observer’s motion. Gravity and inertia became a single phenomenon, not a ‘force’ but merely the tendency of objects to take the simplest possible paths through a space-time distorted by the presence of large masses of matter such as stars and planets.

…

“Hawking devotes two chapters to black holes. Although there is yet no decisive evidence that black holes exist, most cosmologists now are convinced that they do. (The best candidate for a black hole is the invisible part of a binary star system in the constellation of Cygnus, the swan.) Hawking’s major contribution to black hole theory was showing that as a star’s matter falls into a black hole, quantum interactions must occur and particles escape in what is known as “Hawking radiation.” As the title of a chapter indicates, ‘black holes ain’t so black.’ Mini–black holes are tiny structures that may have formed in great numbers after the big bang. Hawking showed that if they exist, radiation will cause them to evaporate and ultimately explode.

“It is not clear whether Hawking is a determinist who thinks history has to be the way it is, or whether chance and free will intervene, although early in his book he raises a curious paradox. If determinism reigns it would impose the outcome of our search for universal laws, but ‘why should it determine that we come to the right conclusions from the evidence? Might it not equally well determine that we draw the wrong conclusions? Or no conclusion at all?’ Because the search has so far proved increasingly successful, Hawking sees no reason to abandon Einstein’s faith that the Old One may be subtle, but not malicious.

…

“As Carl Sagan recognizes in his perceptive introduction, Hawking’s book is almost as much about God as it is about time and the universe,

…or perhaps about the absence of God. The word God fills these pages. Hawking embarks on a quest to answer Einstein’s famous question about whether God had any choice in creating the universe. Hawking is attempting, as he explicitly states, to understand the mind of God. And this makes all the more unexpected the conclusion of the effort, at least so far: a universe with no edge in space, no beginning or end in time, and nothing for a Creator to do.”

–Martin Gardner, The New York Review of Books, June 16, 1988