Tell her that you love her hair, that you love her skin, her lips, because, in truth, you love them more than you love your own

*

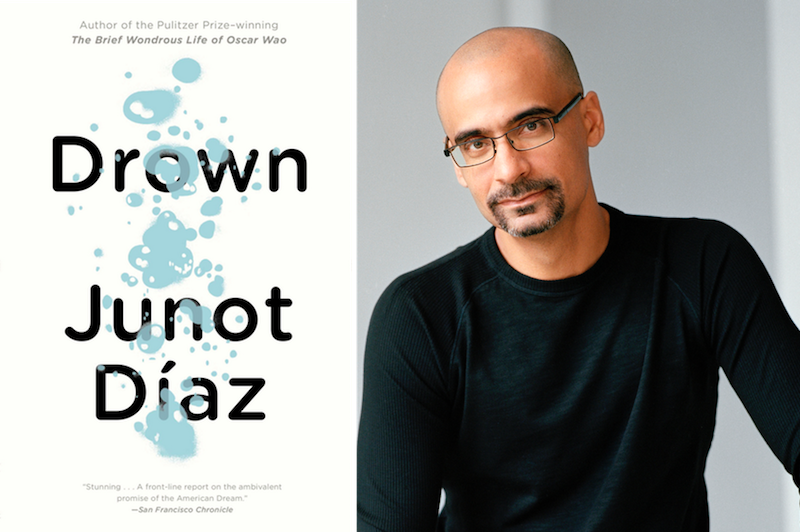

“The young Dominican-American writer Junot Diaz begins his first collection of stories with an epigraph from the Cuban poet Gustavo Perez Firmat to the effect that writing in English ‘already falsifies what I / wanted to tell you.’ For readers with a taste for paradox, it makes an enticing invitation. But in retrospect you wonder what Mr. Diaz is worried about; as a writer, he’s been dealt an ace. Mainstream American literature from William Bradford to Toni Morrison has always been obsessed with outsiders; its Hucks and Holdens are forever duking it out with the King’s English, and writers as different as Ezra Pound, Zora Neale Hurston and Donald Barthelme have delighted in defiling the pure well with highbrow imports, nonstandard vernacular and Rube Goldberg coinages. Despite his professed discomfort, Mr. Diaz is smart enough to play his hand for all it’s worth.

In five of these ten stories, his narrator is young Ramon de las Casas, called Yunior, whose father abandons his wife and children for years before returning to the Dominican Republic and bringing them back with him to New Jersey. In other stories, the nameless tellers may or may not be Yunior, but they’re all young Latino men with the same well-defended sensitivity, uneasy relations with women and obsessive watchfulness.

All these narrators — indeed, all Mr. Diaz’s major characters — feel at a remove from whatever their surroundings may be … And the voice Mr. Diaz has devised for Yunior, an unstable compound of demotic Spanish, white teen-speak and black street talk, is exactly right for a kid uncomfortably feeling his way among his several worlds.

Like Raymond Carver, one of his apparent influences, Mr. Diaz transfigures disorder and disorientation with a rigorous sense of form. He whips story after story into shape by setting up parallel scenes.

…

“Occasionally these stories suffer from an excess of artifice: the gimmick of writing a how-to story in the imperative mood should have been retired after Pam Houston used it (to better effect) in her 1989 story ‘How to Talk to a Hunter.’ And sometimes Mr. Diaz’s figurative language goes over the top, as when he shows us ‘the sun sliding out of the sky like spit off a wall.’ But there’s no such showing off in the steady-handed ‘Negocios,’ a portrait of Yunior’s father — hard-working and neglectful, weak-willed and tyrannical — filtered through the son’s feelings of love, longing and anger.

“The poem Mr. Diaz uses for his epigraph concludes, ‘I / don’t belong to English / though I belong nowhere else.’ That’s as good a history of American literature as you’re apt to find in 10 words, and if Junot Diaz thinks he doesn’t quite belong in this tradition, that suggests he’s smack-dab in the middle.”

–David Gates, The New York Times, September 29, 1996