“The French have a phrase for it. The bastards have a phrase for everything and they are always right. To say goodbye is to die a little.”

*

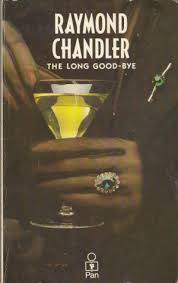

Master of the hard-boiled school of detective fiction and creator of quintessential noir P.I. Phillip Marlowe Raymond Chandler passed away 59 years ago today in La Jolla, California—just a few short, and painful, years after the publication of what many consider to be his finest novel: The Long Goodbye. Written while his wife, whose passing would send the author into a spiral of alcoholism and depression from which he would never recover, was dying, The Long Goodbye is Chandler’s longest and most autobiographical work. In it, through the characters of drunken and depressive genre writer Roger Wade and alcoholic man-out-of-time Terry Lennox, he examines his own flaws and failings—those aspects of his life and career that haunted him to the end.

“Raymond Chandler, generally acknowledged as the foremost creator of hard-boiled detective stories after Dashiell Hammett, has written regrettably little of late. After a large number of first-rate novelettes in the Nineteen Thirties and four distinguished novels, 1939-43, he has produced only two novels in the past eleven years. The first of these, The Little Sister (1949), I found badly disappointing though some critics rated it high among Chandler items: but the newest, The Long Goodbye, (Houghton Mifflin, $3), more than assuages the disappointment and makes one wish that Chandlers were as frequent as Gardners.

This one is rather off the hard-beaten path of Chandler-tana. It’s about private detective Philip Marlowe, of course, as are all Chandler novels, but both Marlowe and his creator seem to have mellowed somewhat in fifteen years. The plot deals relatively little with the professional criminal classes, but rather with the tensions—emotional, psychological and fundamental of the upper middle class.

On the whole, despite occasional outbursts of violence, it’s a moody, brooding book, in which Marlowe is less a detective than a disturbed man of 42 on a quest for some evidence of truth and humanity. The dialogue is as vividly overheated as ever, the plot is clearly constructed and surprisingly resolved, and the book is rich in many sharp glimpses of minor characters and scenes. Perhaps the longest private-eye novel ever written (over 125,000 words!). It is also one of the best—and may well attract readers who normally shun even the leaders in the field.”

–Anthony Boucher, The New York Times, April 25, 1954

*

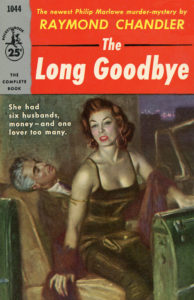

“The difference between this and other Chandler books is that it is longer, so that you get a double helping of everything—nymphomaniacal millionairesses; sad alcoholics; doping doctors; corrupt, sadistic cops; luxury-loving gangsters; beatings up and boppings down. Also Marlow, the honest detective, while retaining his integrity, loses his chastity and accepts the favors of one moderately numphomaniacal, non-homicidal millionaires. He does, however, refuse to share her income and returns to his solitary chess-board in the scruffy bed-sitting-room flat. The plot may not be quite watertight, but who cares about Chandler’s plots so long as his props are all there, and with them, that strange, compulsive, almost edible readability?”

-Maurice Richardson, The Observer, November 29, 1953

*

“A rough, beat ’em up mystery thriller with knives, gun butts, a Mauser 7.65 and loads of sarcasm is The Long Goodbye by Raymond Chandler. Philip Marlow, with his own brand of philosophy once again unravels a mystery that seems to run into dead end, then a new twist brings new facts to life. The events often appear to change the question of ‘Who done it?’ to ‘What happens next?’ And all of a sudden there is a whole new series of unanswered questions.”

–The Daily Times, April 24, 1954

*

“Philip Marlowe’s Ave atque Vale runs to about 500 pages, through the sanguine incidents which attend his casual involvement with Terry Lennox, a rich woman’s kept poodle whom he picks up in a bar. The murder of Sylvia Lennox takes Terry to Mexico, and a confession-suicide (and political influence) closes the case—but not for Marlowe who keeps it alive on a trail of hellcats and hoodlums, a writer with a massive guilt complex and a lovely, loose bitch, to a second murder and its relentless finale…Chandler, a literary roughneck, is probably the most polished exponent of this form of highbrow-lowbrow entertainment and has few equals if many imitators.

–Kirkus Reviews, March 1, 1954

*

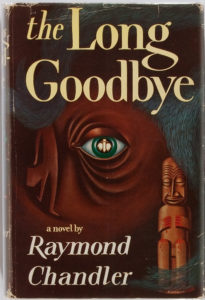

“I shall say that Raymond Chandler seems to me the master of crime fiction, and that The Long Goodbye, if not the best or most technically accomplished of the Marlowe novels, is without question my favourite.

Chandler never wrote with such passionate conviction as he does in this long and darkly tormented work. In the figure of the best-selling but self-hating author Roger Wade, we glimpse an exaggerated version of Chandler himself, who throughout his writing life chafed under the label of ‘mere’ thriller-writer.

He complained repeatedly and with bitterness against highbrow critics, such as Edmund Wilson, who failed to see, Chandler believed, the artistry and stylistic polish of his work. In fact, Chandler was valued and praised, far more than he acknowledged: as a serious drunk, he preferred martyrdom to stardom.

…

“After Lennox has gone from his life, for good, he imagines, Marlowe makes a pilgrimage to Victor’s, the bar where he used to meet his old friend. The image of him sitting alone at the bar as the day wanes is one of the most touching and oddly moving that Chandler ever wrote. As the tough cop Bernie Ohls has it, ‘You live pretty lonely . . .’ Marlowe is supposed to be hard-boiled, but the fact is, inside he’s as soft as the evening light fading in the bar window behind him.”

–Benjamin Black, The Independent, January 21, 2016