Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, in which books journalists from around the US and beyond share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recent gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

This week we spoke to music critic and author, Tim Riley.

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

Tim Riley: I’m a big fan of all the old classical critics, B.H. Haggin, Virgil Thompson, and especially George Bernard Shaw, whose music stuff I first encountered during a Winter Term course at Oberlin. Few people understand Shaw as our first modern critic. The myth holds that his mother taught singing in their home, and he grew up with a great appreciation and understanding of the vocal mechanism, and before he ever established himself as a theatre maven, he reviewed classical concerts regularly for London papers in the 1880s and 1890s. He championed Mozart, who for some inexplicable reason was not popular at the time. Today you can find three volumes of his collected criticism in a handsome edition from Bodley Head, and he reads like Paul McCartney’s cranky grandfather in A Hard Day’s Night. I think it must have been a kick to read Shaw in the dailies after hearing the same concerts (“Music is the brandy of the damned…,” and “From Mozart I learnt to say important things in a conversational way…”)

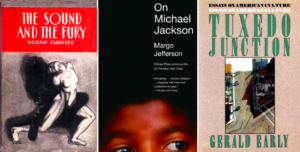

I like to think I would have been hip to Faulkner’s non-linear narrative strategy in The Sound and the Fury, and Absalom, Absalom! when they appeared in the late 1920s and 1930s, but that’s hubris. That those books still stun readers today proves he had something beyond narration. I read those books in college, and listen to them on audio books, and they still instill a sense of awe at the power of story. I particularly like the way Toni Morrison plays with echoes of Faulkner’s ideas without cloying at this style, far too easy to imitate. Then again, I’m a music critic, don’t devote a lot of time to reviewing fiction…but it has influenced me a LOT.

Other favorites: Gerald Early’s Tuxedo Junction had a strong influence on my approach; Margo Jefferson’s On Michael Jackson, which I still use in class; Ellen Willis’ Beginning to See the Light (some of the best stuff on the Velvet Underground, and the Who); Stanley Booth’s Sympathy for the Devil holds up very well, reread that recently. That’s a book that reads very differently in your twenties than in your fifties.

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

TR: I’ve had a long fascination with the Altamont concert in 1969, where Hells Angels murdered a young black man named Meredith Hunter. That this happened at a Rolling Stones concert, and that he came with a white date from Berkeley high school, has always made the event a locus of my Emerson presentations on rock’s racial themes. Bay Area journalist Joel Selvin came out with Altamont last year and provided a fascinating reporter’s log of the event and its aftermath. Just recently, Saul Austerlitz came out with a second treatment (Just a Shot Away), focusing on Hunter as a primary subject, which I’ve always fantasized as the best way to focus this material.

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

TR: That we only do it for free books. They’re not free: you pay in time, and interactions with flacks who deluge you with pitches and schemes no matter how fantastical. Nobody does it for the money or the booty, you have to wake up anxious to get to the next book in your pile, and plow through lots of less-than-great work to find worthwhile non-fiction; I can’t imagine what it’s like for fiction reviewers. Writing your own books keeps you humble: it takes so much effort to simply start, maintain a schedule, and then finish, that I don’t take any pleasure in torching authors. I enjoy a good takedown as much as anybody, and would have loved to have taken on Albert Goldman, for example, who was simply a wrongheaded fool. But for the most part it takes a lot of work and talent to create a mediocre effort.

It’s also a myth, I think, that critics want people to agree with them. I try to use persuasion in my arguments, but mostly it’s the sound of me refining my own responses, and I’m happy when someone else comes along and presents another perfectly reasonable yet apposite point of view on the same material. Don’t read to agree, read to sharpen your own thoughts.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

TR: We had a presentation from a Shakespeare scholar on the whole #1Lear controversy from a couple years ago, where Holger Syme took down One King Lear by Brian Vickers via twitter, and I though that was terrific coming from an academic, an inspired rock’n’roll move. Weird that no rock critic thought of that first, although we did see compressed career summaries from an anonymous critic on twitter (who’s since disappeared) that were pretty fetching. @SPINreviews launched a brief twitter-based review column, but hasn’t kept it alive. Chris Weingarten compiled his full set of @1000timesyes tweet-reviews into a self-published book.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

TR: Margo Jefferson, Gerald Early, Clive Davis, David Thomson, Michelle Goldberg.

*

Tim Riley is a critic and Emerson College associate professor who reviews pop and classical music for NPR’s Here & Now and On Point, and has contributed to the New York Times, Radio Silence, Slate, and Salon. The NYT Book Review hailed his first book, Tell Me Why: A Beatles Commentary, for bringing “new insight to the act we’ve known for all these years.” He has since authored Hard Rain: A Dylan Commentary, Madonna: Illustrated, Fever: How Rock ‘n’ Roll Transformed Gender, and Lennon: Man, Myth, Music. In 2016, he won the LA Press/NAEJA Best Cultural Critic Award for his truthdig reviews.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.