Jess Row’s White Flights is published today. He shares three books and two films about white flight.

Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides

Middlesex is (among its many other excellent qualities) probably the closest to an epic of white flight American literature will ever have, as it follows one Greek immigrant family along the entire trajectory of assimilation into whiteness—from their first arrival in an unfamiliar city (Detroit), their slow accumulation of capital and status, their departure from the city in the midst of the 1968 uprising, their fraught, unhappy absorption into suburban white prosperity in Grosse Pointe, and the bitter departure of the alienated second generation—who turns homeward and creates the narrative.

Jane Ciabattari: It’s intriguing to examine Middlesex from that perspective. At what point in the novel (or in its historic moments) do you think Eugenides best captures the complicated relationships across racial lines in this culture?

Jess Row: The scenes that capture the 1968 uprising from a child’s point of view (I write about them in White Flights) are indelible, and my favorite part of the novel—they’re a perfect example of what the Russian critic Viktor Shklovsky called “defamiliarization”or “estrangement.” For example: the moment when Callie, the child protagonist, sees an army tank rolling slowly through her idyllic neighborhood, and then grabs her bike to ride and take a closer look. But I also love the moments when Callie is being absorbed into the suburban culture of Grosse Pointe, when she makes friends who live in vast houses where no one ever seems to be home.

The Turner House by Angela Flournoy

The Turner House would be a perfect book to pair with Middlesex, as it deals with the city that the characters in Middlesex left behind—the Detroit African Americans struggled to improve, and survive, in the decades after 1968. Like Middlesex, The Turner House is a family epic stretching across generations, centered around the haunting of a house that (like many houses in Detroit) becomes derelict and almost valueless, no matter how much the younger members of the family still cherish it.

JC: The sections of the novel set in 1944 are such an effective contrast to the twenty-first century narrative. Do you have a favorite character?

JR: I have to admit I didn’t have a favorite character; I enjoyed absorbing the family epic as a whole, and the ways the characters so richly depend on one another. In a way, my favorite “presence” (not precisely a character) was the haint, the ghost, who keeps appearing and reappearing when we think the realist narrative has progressed beyond it.

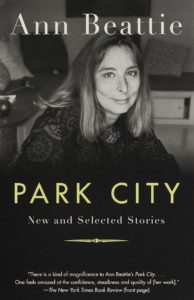

Park City: New and Selected Stories by Ann Beattie

Although I didn’t have the chance to write about Beattie in White Flights, her work is an evocative example of how a certain subset of the American white literary imagination—which once would have been called “urbane”—migrated out of cities in the 1980s and 1990s, first to the New York suburbs (witness a story like “The Cinderella Waltz”) and then to idealized retreats and idylls: Maine, Key West, Park City. Beattie is one of those writers who see real estate as a subject of continuous fascination (as in one of her most famous stories, “Janus”) and as a vector for desire and frustration, and the restlessness of her characters (like those of another key writer in this tradition, Richard Ford) can easily be read as a kind of postmodern settler psychology, a repetition of Manifest Destiny as farce.

JC: Intriguing that Andy Solomon, in his 1998 Washington Post review, compared this collection to “a boxed set of Miles Davis CDs…both superb in itself and an essential piece of history.” Although the locations of her stories shift, her characters are still mostly New Yorkers (or natives of other cities). How do you see the title story, fitting into your theme?

JR: Exactly! This is what I meant about her work’s quote-unquote “urbane” sensibility; her characters always refer back to New York, or other big cities, as a template for how they understand life and culture and the past, but they find themselves in these places that are (for them, not for everyone) escapes. I went back and reread the title story to answer your question, since I hadn’t looked at it in many years, and it contains a line that’s almost too perfect for my purposes. A worldly 14-year-old girl from Los Angeles is cooped up in a somewhat shady condo in Park City, waiting for her mother to finish a screenwriting seminar, and she looks around (having reviewed the entertainment option, including whitewater rafting and mini golf) and says, “If this is what the Wild West has become, fuck it.” There you have Manifest Destiny-as-farce in a nutshell.

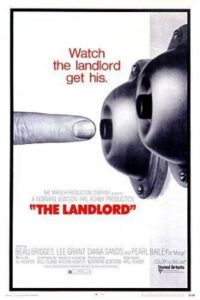

The Landlord (1970), Dir. by Hal Ashby [film]

The Landlord is probably the greatest American film ever made about gentrification—the other dimension, or direction, of white flight. Beau Bridges plays Elgar Enders, the daffy heir to a WASP family fortune, who decides on a whim to buy a brownstone in Park Slope—at that time considered a slum—and transform it into an eccentric work of art, conveniently forgetting the black families who already live there. Enders’s transformation is as jarring, troubling, and bleakly funny in 2019 as it was nearly fifty years ago.

JC: The Landlord is based on Philadelphia-born writer Kristin Hunter’s 1966 novel, although shifted to Park Slope and changed in tone. “The point of the novel is that an immature white boy, by being pushed into contact with this bunch, is forced to grow up, to be responsible, to see reality,” she explained in 1984. “White men are allowed to remain boys until great ages, because they’re protected.” In the film, Enders ends up being educated by his tenants, including a former jazz singer played by the inimitable Pearl Bailey. What, for you, is the pivotal moment in his transformation?

JR: I wouldn’t exactly say “educated” by his tenants, although it’s true that the film is full of the problematic trope of black people doing the emotional labor of pointing out of the obvious to white people; I think The Landlord really gets interesting when Enders decides he’s not going to run away, but rather live with his tenants and share their lives, in awkward (and funny) ways. That’s what’s so great about Hal Ashby’s directing style—he lets the camera linger on the cringe-worthy moments for as long as possible. For me the pivotal dramatic moment is when Enders falls in love with a black woman (and then another—but that’s as much as I’ll say to avoid spoiling the plot). The Landlord is very much a film about the possibility of, and fear of, interracial love, which is something I write about at length in White Flights. Can an interracial relationship survive, when it’s weighed down with so much metaphorical and symbolic significance? Ashby finds a way of turning even this question into a kind of hideous comedy.

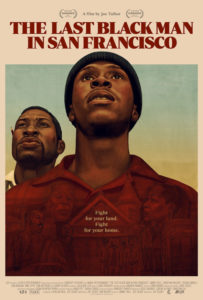

The Last Black Man in San Francisco (2019), dir. by Joe Talbot

An astonishingly beautiful film, just released this summer, that tells the story of one young black man’s attempt to reclaim his grandfather’s house in San Francisco as an imaginative, fantastic, artistic act. Anyone who has ever had a family house—one occupied by multiple generations, still filled with artifacts and memories of a distant era—will recognize the devastating asymmetry between our feelings and the brutal market forces that have hollowed out American cities in the last half century. It’s a film that evokes wonder and anger in equal measure.

JC: It’s a film that shows San Francisco’s historic black communities—Hunter’s Point, the Fillmore—as gentrification grows, and the complicated emotions that brings to a young man who grew up in the Fillmore. (I love the visual artistry throughout, not to mention the skateboarding scenes.) There’s a scene in which he talks to a couple of newbies on a bus and tells them, “You can’t hate [this city] unless you love it.” How do you think this ambivalence works to make this film so powerful?

JR: That question points to a very basic social ambivalence about cities in American life that has terrible repercussions. In the 20th century, urban planners assumed that a city needed housing for low- and middle-income residents, and in many cases, built that housing or encouraged private developers to build it. That’s the origin of public housing, and also massive public-private developments like Stuyvesant Town and Co-op City in New York. In the 1980s and 1990s, the real estate industry and its investors convinced cities and states to change course fundamentally and deregulate the housing market, loosening many of the restrictions that protected those tenants. What this led to, in psychological terms, is a widespread belief that no one has “the right” to a home in the city, even if they’ve lived there for generations.

What we see in that scene in the movie is an illustration of this paradox: people who have lived in San Francisco for generations, who are true residents of the city (and, it should be said, have paid taxes, voted, and participated in civic life in every way) are displaced, and people who have no particular stake in any city, and who think of themselves as cosmopolitans (without knowing at all what the term actually means) move in, because they have the transportable capital—not just money but the education, connections, and social capital to be able to work and live nearly anywhere.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·