On a map, a border is a thin, black line—a scribble of ink delineating where the jurisdiction of one nation ends and another begins. It is a final thing: negotiated, tweaked, surveyed and marked. Blood was spilled along every international boundary in the world. When the fighting finished, more died trying to get to the other side.

Academics call either side of a new boundary a “borderland,” where the line is vague and populations on both sides are still interconnected. As the border becomes more defined and enforced, it evolves into “bordered lands”—where movement and commerce are restricted. What was once a singular region becomes two, and both sides develop individual identities, economies, and cultures.

America’s borders exist somewhere between these two. In the north and south, they are a place of commerce, a smuggler’s haven, a barrier that divides families and communities. U.S. borders become political pawns to politicians looking to control their constituency, bargaining chips in international trade deals, the object of threats to neighboring countries that do not bend to the desires of a leader.

Collected here are seven books that discuss two things often left out of border discussions: land and people. The land could not care less what lines are drawn across it. It will always retain its own geological, climactic, and ecological borders (that outlast anything drawn by man). As for the people, many were living along the line before it was ever considered—some for thousands of years before newcomers arrived and divvied it up.

The books below tell these stories. They are real narratives about the way things really are along the boundary, not what they look like on a map.

*

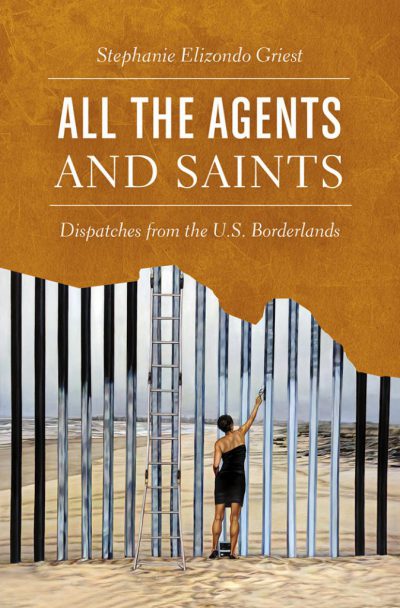

All the Agents and Saints: Dispatches from the U.S. Borderlands by Stephanie Elizondo Griest

Travel Writer Stephanie Elizondo, a native South Texan, researched Mexican revolutionaries, Spanish conquistadors, ranchers, Texas Rangers, and entrepreneurs in her portrait of the Rio Grande Valley. Then she compared it with another ethnic group displaced by a border: the Mohawks of the Awkwesasne Nation on the U.S.-Canada border. The story of the two vastly different regions and communities shows some striking similarities—like the way that ill-conceived treaties stole their land, how children were forced into English-only schools, and how entrepreneurs led the charge to take over their land. The result is a disturbing examination of how much of the U.S. came to be and how the original residents of this borderland continue to be oppressed.

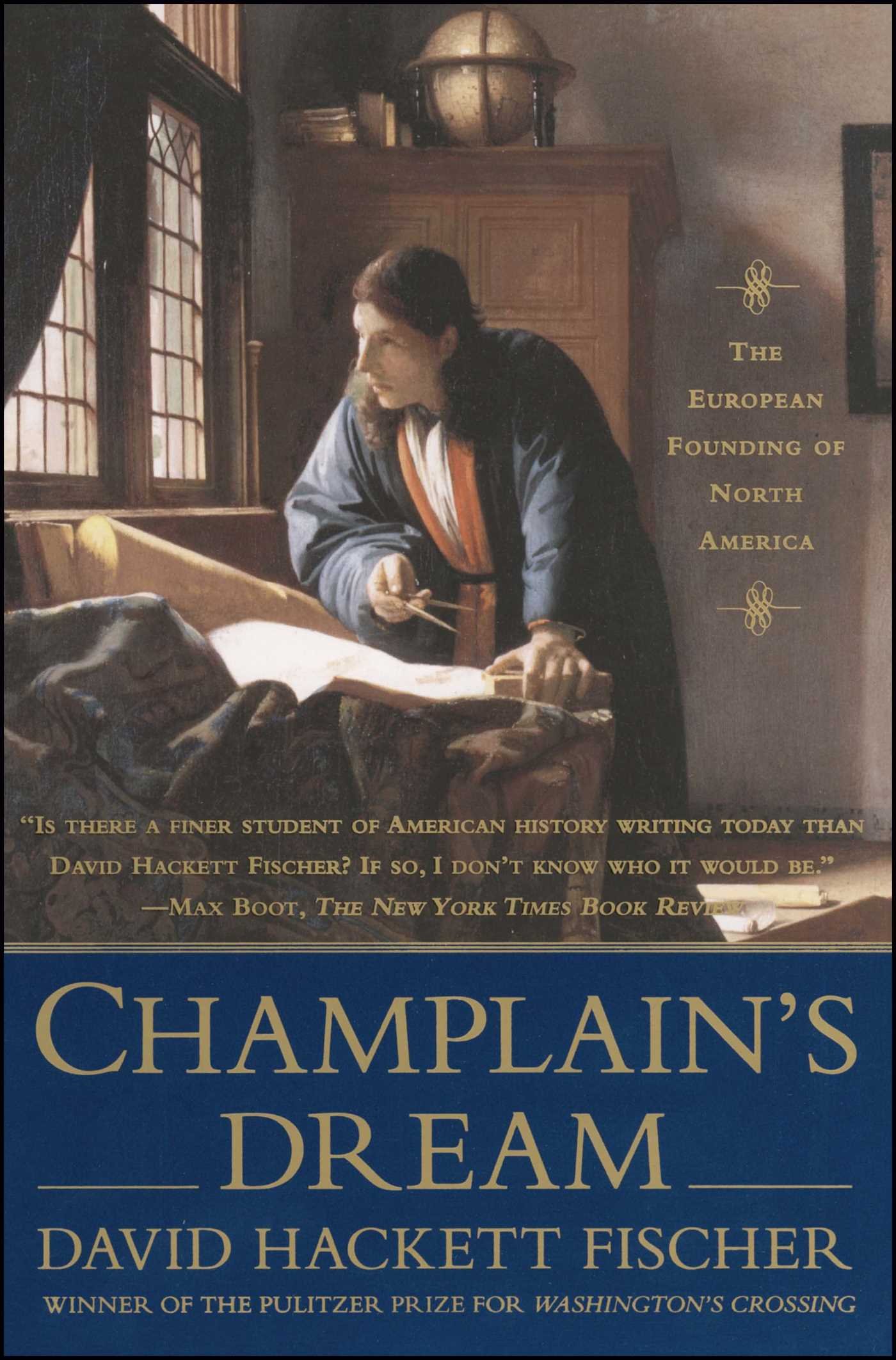

Champlain’s Dream by David Hackett Fischer

To see what life was like in North America before borders, read David Hackett Fischer’s masterpiece. Fischer travels in Champlain’s footsteps from Brittany to Nova Scotia, recounting the great, somewhat unknown explorer who inadvertently drew the first thousand miles of the U.S.-Canada Border. Champlain’s meticulous journal is the basis for much of the story and follows the Frenchman into battle against Mohawk armies, down death-defying whitewater on the Saint Lawrence River, and on foot farther inland than any white man had before. Champlain’s ease and lasting friendship with Native American chiefs throughout speaks to his humanist faith and fortitude. Following him into the wilds of interior America—all the way to the Great Lakes—the reader begins to understand America before it became America.

The Line Becomes a River: Dispatches from the Border by Francisco Cantú

Francisco Cantú once worked for the U.S. Border Patrol. His mother was a park ranger and also the daughter of a Mexican immigrant. While on duty, he was stationed in remote regions of the southwest border to watch for smugglers and illegal immigrants. Some died trying to cross; others were taken into custody. The job haunted Cantú and after an immigrant friend disappeared over the border—traveling to Mexico to visit his dying mother—and didn’t return, Cantú realized that he had to write about it. It is clear that the border is in his blood as he describes violence, injustice, and the brutal landscape of America’s southwest boundary. One of the more shocking revelations is how far that violence and injustice reaches into both nations, well beyond the line.

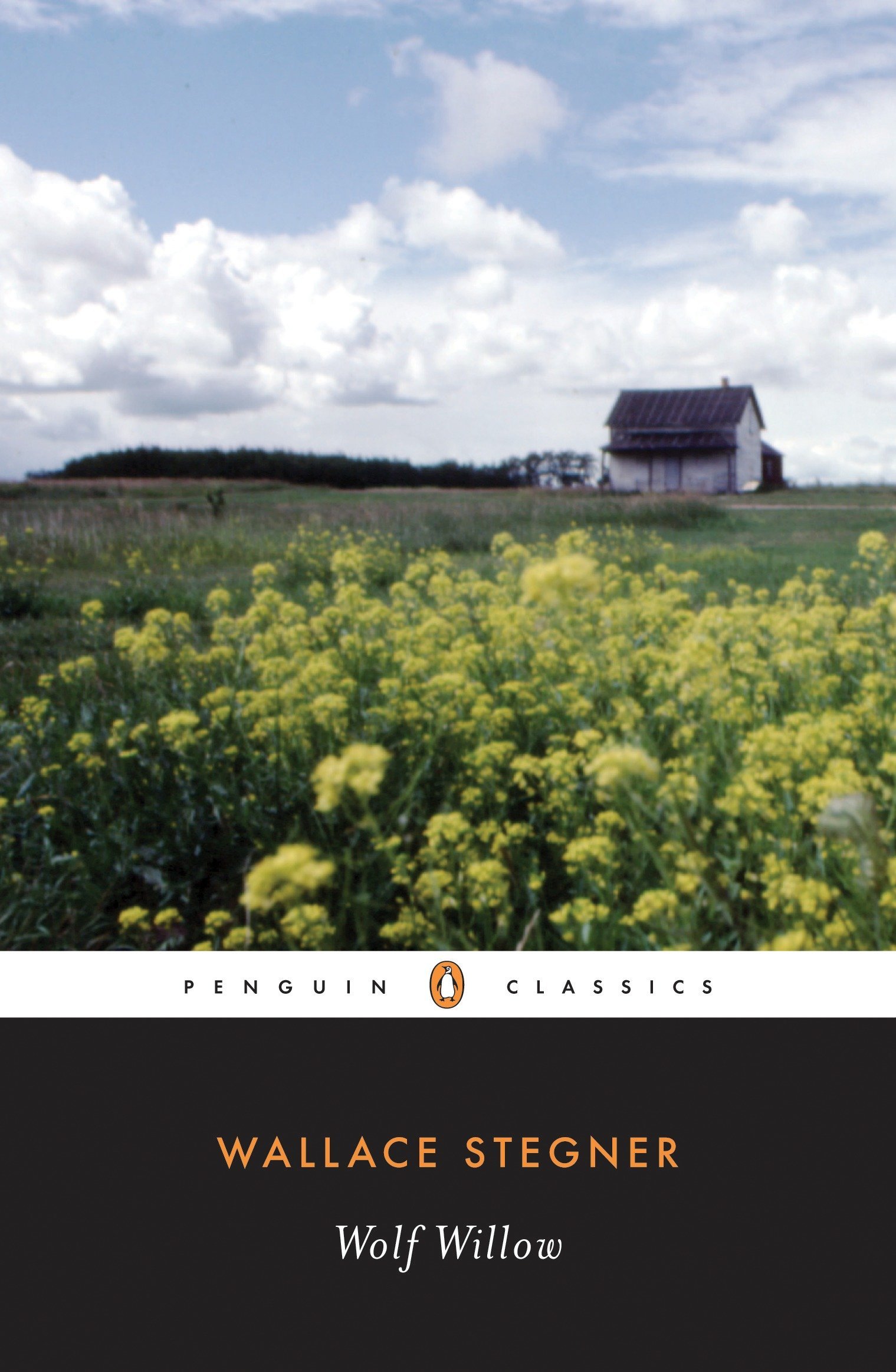

Wolf Willow by Wallace Stegner

Wallace Stegner’s memoir about growing up along the U.S.-Canada border in Montana is a portrait of the borderland, set sometime between when the line was drawn and when people started actually observing it. Stegner lived in an abandoned dining car near the Canadian Pacific Railroad as a child. In the summer, his family moved to a shack right on the boundary to farm wheat on what was then an honest-to-God no man’s land. “The first settlement in the Cypress Hills country was a village of métis winterers,” he writes. “The second was a short-lived Hudson’s Bay Company post on Chimney Coulee, the third was the Mounted Police headquarters at Fort Walsh, the fourth was a Mountie outpost erected on the site of the burned Hudson’s Bay Company buildings to keep an eye on Sitting Bull and other Indians who congregated in that country in alarming numbers after the big troubles of the 1870’s.”

The Crossing by Cormac McCarthy

No border reading list is complete without at least one volume from Cormac McCarthy’s trilogy. His raw and insanely detailed descriptions of the landscape and people on both sides of the border make you nostalgic for the age when the accuracy of your six-shooter determined how far north or south you could range. As the young Billy Parham trots south, with a wounded wolf in tow, McCarthy writes, “[they] crossed sometime near noon the international boundary line into Mexico, State of Sonora, undifferentiated in its terrain from the country they quit, and yet wholly alien and wholly strange.” A teacher I once had put his finger on McCarthy’s descriptions of the borderland: “He knows the names of things.”

Arc of the Medicine Line: Mapping the World’s Longest Undefended Border Across the Western Plains

by Tony Rees

You rarely hear about how borders were drawn. Tony Rees’s meticulously researched Arc of the Medicine Line tracks the British and American surveyors, astronomers, axemen, soldiers, cooks and laborers as they haul sixty-foot Gunter’s chains, theodolite survey telescopes, air levels, sextants, compasses, and synchronized chronometers—top-of-the-line equipment for mid-Victorian field science—more than a thousand miles along the U.S.-Canada border. The Northern Boundary Commission of the mid-1800s, dressed Hudson’s Bay Company hooded greatcoats, moccasins, and sealskin pants, fought off mosquitoes, extreme heat, thunderstorms, and prairie fires while painstakingly making their way across the northern plains. Much of the border ran straight through Sioux territory, making British surveyors, who had never had any problems with the Sioux nation, terrified of being mistaken for American invaders. Sioux scouts were uninterested in the bearded and bespectacled foreigners and three years later the American commission’s 140 horses, 38 wagons, and 270 tons of supplies reached their destination: a limestone pyramid on Montana’s Mount Akamina that marked the end of the known border reaching east from the Pacific.

Border Contraband: A History of Smuggling Across the RioGrande by George T. Díaz

Stories about mobsters running booze over the border tend to focus on the forested northern fringe of the U.S. But there were bootleggers in the south during Prohibition as well. Tequileros delivered tequila from distilleries in Mexico to many southwestern towns and cities. Most of the runners were men, but there were a few women as well. The Texas Rangers infamously targeted (and murdered) hundreds of tequileros before they were taken into custody—a harbinger of the violence that would continue along the southern border. This book offers an interesting perspective into the first days of smuggling across the bushland of the U.S.-Mexico border, along some of the same back trails that smugglers use today.