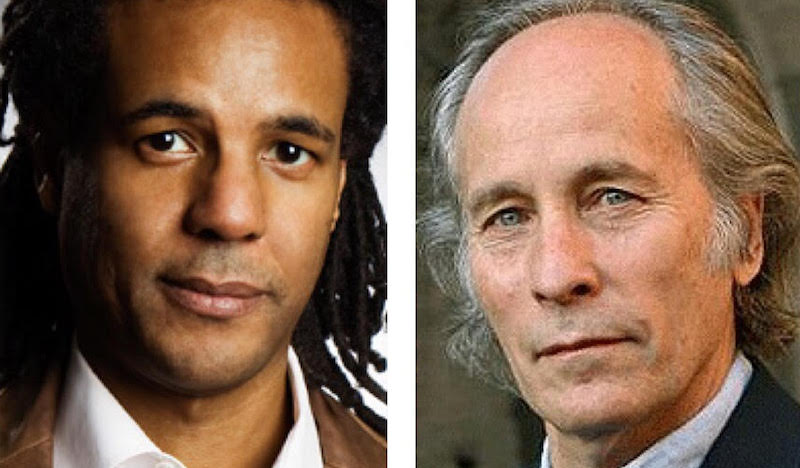

“I would like to warn the many other people who panned the book that they might want to get a rain poncho, in case of inclement Ford.”

-Colson Whitehead, in response to being spat on by Pulitzer Prize-winner Richard Ford in 2002

*

Yesterday, an article by Guardian and Observer Books Editor Claire Armistead rekindled our interest in one of the literary world’s most notorious feuds. In her detailing of Richard Ford’s run-in’s down through the years with those authors who, in the pages of the New York Times, have been less-than-complimentary about his books, Armistead considered Ford’s behavior in the age of social media.

In light of this, we at Book Marks thought we’d take you back to the beginning of Ford and Whitehead’s falling-out, and give you a taste of the review in question.

*

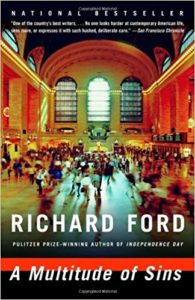

“First things first: there is hardly a multitude of sins in Richard Ford’s latest volume of short stories. There is certainly a plenitude of lust, a brand of lukewarm lust that seems to have less to do with deep urges than with a need for a warm body you are not married to. There are a multitude of personality deficits on display, but they rarely approach the level of sin. If self-absorption, vague yearnings and a nagging sense of incompleteness are sins, then surely I will burn for all eternity, and I will save you a seat.

Almost every story deals with adultery, invariably in one of two stages: in the final dog days of an affair, or in the aftermath of an affair. The characters are nearly indistinguishable. If I were an epidemiologist, I’d say that some sort of spiritual epidemic had overtaken a segment of our nation’s white middle-class professionals, and has started to afflict white upper-middle-class professionals. These characters could use some good advice, and if they had friends, they might be able to ask for it, but they don’t have friends. Sometimes the men are named Roger or Tom, sometimes the women are named Nancy or Frances. If they have children, we rarely see them. Some of them meet in fancy hotel rooms, others prefer out-of-the-way motels. Whatever the specifics, adulterous or not, they bide their time for opportunities to offer portentous declarations about their predicaments like: ”Other people affect you. It’s really no more complicated than that’ and ‘I am sure now that all of this had to do with my impending failures.’ These declarations will strike you as plain-spoken and hard-earned wisdom, or easy banalities, depending on your mood or level of generosity.

“It is the end of an affair. An affair has just ended. A Muted Epiphany caps off each story, causing you to believe that perhaps, maybe, the protagonist might have learned an indefinable ‘something’ (one of Richard Ford’s favorite words), but it is hard to remain convinced. There is always another sinner and another sinned-against treading water. Just turn the page.

These folks are plain mushy. They share a number of traits with Frank Bascombe, the protagonist of Ford’s novels The Sportswriter and Independence Day, but in those novels Frank earns our goodwill, and a great deal more. Bascombe is adrift, leading ‘the normal applauseless life of us all,’ but over the course of hundreds of pages manages to engage, despite, and perhaps because of, his inarticulate articulateness. ‘For some reason I have a feeling I won’t see her for a long time,’ Bascombe says of his wife early in The Sportswriter, ‘that something is over and something begun, though I cannot tell you for the life of me what those somethings might be.’ In A Multitude of Sins, the characters’ sense of befuddlement comes to infect, but never to enlighten, the reader.

“Nothing is extraneous. Since everything is there for a reason, and thus imbued with a purpose—why else would it be there?—each rhetorical prop radiates in neon, one of Chekhov’s guns on the wall waiting to go off in the third act. Will the man in the wheelchair, glimpsed by Nancy in ‘Charity,’ reappear before story’s end? Yes, and he will be flying a kite. And the kite will soar … A man in a wheelchair cannot just be a man in a wheelchair; he must be a vehicle to help a lame metaphor get around. Such is the method of the Well-Crafted Short Story. These stories, placed back to back, start to show their strings, although puppet master is perhaps not the way Ford would describe himself. When asked last year by The Kenyon Review what kind of relationship he has with his characters, Ford replied: ‘Master to slave. Sometimes I hear them at night singing over in their cabins.’ Singing. So that’s what that was. It sounded like whining.”

–Colson Whitehead, The New York Times, March 3, 2002

***

Editor’s note: A previous incarnation of this post included a passage from the above mentioned Guardian article which quoted two authors’ social media posts on this subject. It has been brought to our attention that said quotes were obtained without permission from either of them. In support of these authors we have removed the passage in question.

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.