I long for the days of disorder.

I want them back, the days when I was alive on the earth,

rippling in the quick of my skin, heedless and real.

*

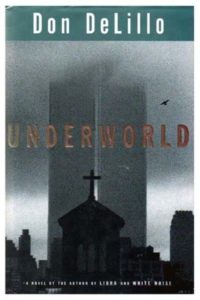

“Expect a lot from the next sentence. Among its other virtues, the title of Don DeLillo’s heavily brilliant new book gives a convenient answer to the Big Question about the American novel: Where has the mainstream been hiding? The grand old men, the universal voices of the late-middle century (predominantly the great Jews, and John Updike), are getting older and grander, but the land they preside over looked to be shrinking. Furthermore, it seemed that their numbers were not being replenished by writers of comparable centrality. Was this an epochal change, a major extinction? No. It was a strategic lull.

Something atomized the mainstream. The next wave of genius was there, but not visibly, not publicly. Inasmuch as the mainstream was an institution, these writers could not work within it. They went underground, they sought an underworld of codes and shadows: incognito, incommunicado, and quietly dissident, their literary reputations largely cult-borne. But now the condition that caused the great discontinuity in American letters has come to an end. The novelists are climbing out of the bunker. Don DeLillo’s exact contemporaries, Robert Stone and Thomas Pynchon, seem poised for a fuller expansion. DeLillo himself, however, suddenly fills the sky. Underworld may or may not be a great novel, but there is no doubt that it renders DeLillo a great novelist.

“The new novel is Don DeLillo’s wake for the cold war. According to its argument, the discontinuity in American cultural life had a primary cause: nuclear weapons. The hiatus was inaugurated on the day that Truman loosed the force from which the sun draws its powers against those who brought war to the Far East, and was institutionalized four years later when the Soviet Union started to attain rough parity. Cosmic might was now being wielded by mortal hands, and by the State, which made the appropriate adjustments. The State was your enemy’s enemy; but nuclear logic decreed that the State was no longer your friend. In one of the novel’s childhood scenes, the schoolteacher (a nun) issues her class dog tags:

‘The tags were designed to help rescue workers identify children who were lost, missing, injured, maimed, mutilated, unconscious or dead in the hours following the onset of atomic war. . . . Now that they had the tags, their names inscribed on wispy tin, the drill was not a remote exercise but was all about them, and so was atomic war.’

Nuclear war never happened, but this was the nuclear experience, unknowable to anyone born too soon or too late. In order to know what it was, you have to have been a schoolchild, crouched under your desk, hoping it would protect you from the end of the world. How people rearranged their lives around this moral void, with its exorbitant terror and absurdity, is DeLillo’s subject. Perhaps it always has been. The new novel, at any rate, is an 827-page damage-check.

“Underworld surges with magisterial confidence through time (the last half century) and through space (Harlem, Phoenix, Vietnam, Kazakstan, Texas, the Bronx), mingling fictional characters with various heroes of cultural history (Sinatra, Hoover, Lenny Bruce). But its true loci are ‘the white spaces on the map,’ the test sites, and its main actors are psychological ‘downwinders,’ victims of the fallout from all the blasts—blasts actual and imagined. DeLillo, the poet of paranoia and the ‘world hum,’ pursues his theme unstridently; he is tenacious without being tendentious. Yet even his portraits of bland, hopeful, pre-postmodern American life—his Americana—glow with the sick light of betrayal, of innocence traduced or abused. The ‘great thrown shadow’ has now receded and terror has returned to the merely local. MAD (Mutual Assured Destruction) was exploded; and the bombs did not detonate. Still, the press-ganged children who wore the dog tags must live with a discontinuity in their minds and hearts. DeLillo’s prologue is called ‘The Triumph of Death,’ after the Breughel painting. In the end, death didn’t triumph. It just ruled, for 50 years. I take DeLillo to be saying that all our better feelings took a beating during those decades. An ambient mortal fear constrained us. Love, even parental love, got harder to do.

The protagonist, Nick Shay, works for a company called Waste Containment. And Underworld is among other things a witty and dramatic meditation on excreta, voidance, leavings, garbage, junk, slag, dreck … In White Noise the famous ‘airborne toxic event’ was the result of a military-industrial accident. But it was also DeLillo’s metaphor for television—for the virulent ubiquity of the media spore. Explaining a recent inanity of his daughter, Shay’s co-worker ‘made a TV screen with his hands, thumbs horizontal, index fingers upright, and he looked out at me from inside the frame, eyes crossed, tongue lolling in his head.’ DeLillo’s way with dialogue is not only inimitably comic; it also mounts an attack on the distortions, the jumbled sound bites, of our square-eyed age.

“It should be said in conclusion that those who stay with this book will experience an entirely unexpected reward. Underworld is sprawling rather than monumental, and it is diffuse in a way that a long novel needn’t necessarily be. There is an interval, approaching halfway, when the performance goes awful quiet. But then it rebuilds, regathering all its mass. As I noticed the surprising number of approximations DeLillo settles for, my feelings about the author began to change. Reading his corpus, sensing the rigor of his language, the near-inhuman discipline of his perceptions and the peeled eyeball of his gaze, you often feared for the man’s equilibrium. Yet who was the man? DeLillo is normally quite absent from his fiction—a spectral intelligence. Underworld is his most demanding novel but it is also his most transparent. It has an undertow of personal pain, having to do with fateful irreversibilities in a young life—a register that DeLillo has never touched before. This isn’t Meet the Author. It is the earned but privileged intimacy that comes when you see a writer whole. The critic F. R. Leavis called it the ‘sense of pregnant arrest.’

‘But the bombs were not released. . . . The missiles remained in the rotary launchers. The men came back and the cities were not destroyed.’ Just so. Now that the cold war is gone, the planet becomes less ‘interesting’ in the Chinese sense (ancient animadversion: May you live in interesting times). But it isn’t every day, or even every decade, that one sees the ascension of a great writer. This means that from now on we will all be living in more interesting times. Which is my whole juxt.”

–Martin Amis, The New York Times Book Review, October 5, 1997