When I see an actual flesh-and-blood worker in conflict with his natural enemy, the policeman, I do not have to ask myself which side I am on

*

“The George Orwell who went to Spain in late 1936 was a man who could analyze his feelings when he shot for the first time a human being and yet take careful aim, who could calmly examine the risks he was running without pretending not to be afraid, who could set down his exact emotions on receiving what seemed to be a mortal wound. He had a sharp eye for human weaknesses, his own as well as other people’s. When, for example, he returned from the front to Barcelona in the spring of 1937, he deplored the growing extravagance, adding: ‘But God forbid that I should pretend to any personal superiority. I admit to having wallowed in every luxury that I had money to buy.’ He loved the Spanish people and was constantly exasperated with them. ‘In theory,’ he wrote, ‘I rather admire the Spaniards for not sharing our time neurosis; but unfortunately I share it myself.’

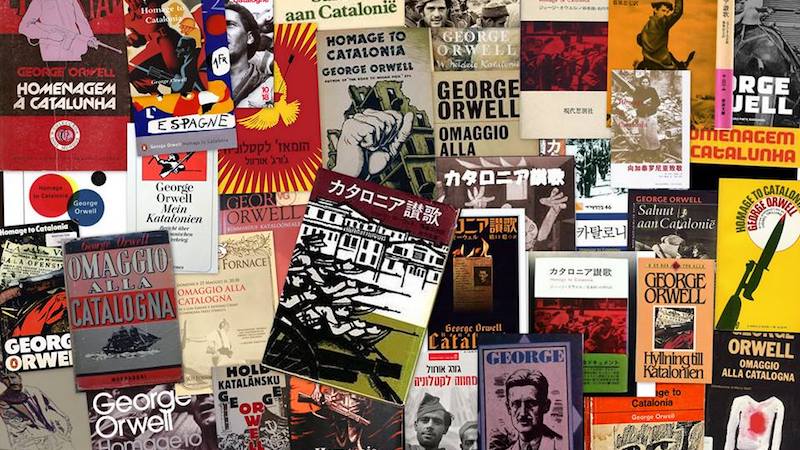

Because of what Orwell was, Homage to Catalonia, his account of his experiences in the Spanish civil war, is worth reading today, fifteen years after it was written. It was published in England in 1938. Now, two years after the author’s death, it has been published over here, and it is alive, whereas most of the books about Spain that were published in this country in the late Thirties and were read are dead.

That Orwell should have gone to Spain was in no wise remarkable. Writers were streaming into Loyalist Spain from all over Europe and America—Malraux and Koestler and Hemingway and Dos Passos and countless others—and many of those who didn’t go felt frustrated and guilty. Some went to fight and some to write, but they were all partisans, all certain that the issue was clear-cut—the people vs. tyranny.

“Orwell was a partisan, too. He was not a Communist, as were Malraux and Koestler, but he was a revolutionary Socialist, affiliated with the Independent Labor party. He went to Spain, he said, to write some newspaper articles, but he probably knew all the time that he would get into the war if it seemed to be his kind of fight. It did: he promptly enlisted, ‘because at that time and in that place it seemed the only conceivable thing to do.’

In Barcelona, he felt, all men were equal, and there was hope in the air. ‘There was much in it that I did not understand,’ he wrote; ‘in some ways I did not even like it, but I recognized it immediately as a state of affairs worth fighting for.’

There were several political parties on the Loyalist side in Spain, and to begin with each of them had its own militia. The militia Orwell joined, more or less by accident, had been organized by P.O.U.M., the Partido Obrero de Unificacion Marxista, a rather small group of anti-Stalinist revolutionaries. After some weeks of great hardship and little action of the Zaragoza front he was hospitalized for ten days with a poisoned hand. He returned to the front, so plenty of action for a time and then, toward the end of April, went on to leave to Barcelona, where his wife was waiting for him.

“Thus he happened to be in Barcelona at the time of what became known as the P.O.U.M. uprising. On May 3 a struggle began between the syndicalist unions and the Catalonian police force. The issue seemed perfectly clear to Orwell: ‘I have no particular love for the idealized “worker” as he appears in the bourgeois Communist’s mind, but when I see an actual flesh-and-blood worker in conflict with his natural enemy, the policeman, I do not have to ask myself which side I am on.’ What he did was to spend three nights on the roof of a moving-picture house, watching over P.O.U.M. headquarters. Then troops came from Valencia, and the street fighting stopped.

Orwell went back to the front and ten days later got a bullet through his neck that just missed the carotid artery. When he came out of the hospital his right hand was paralyzed and he had lost his voice—permanently, the doctor said, though that turned out not to be true. As he was going through the process of getting a medical discharge he was suddenly warned by friends that the P.O.U.M. had been suppressed and many of its members jailed. Sleeping in ruins and vacant lots, he managed to avoid the police for a few days, and then he and his wife, with a good deal of luck, escaped into France. He began immediately to write this book.

“That he could have written so objective a book so soon after his almost fatal involvement in the war itself and in the partisan conflict seems miraculous. For that matter, it is remarkable that he wrote the book at all. Orwell was not the only man to be disillusioned with communism in Spain. Koestler’s disillusionment began there, and he let it find expression in his first novel, The Gladiators, but he did not talk then about what he had seen in Spain. Dos Passos, already far on the path of disenchantment, was deeply troubled by what he saw and heard, but he was cautious in voicing his doubts. There were others, too, but almost all of them were silenced by the fear that they would damage the Loyalist cause. Orwell recognized no times and seasons for telling the truth; he spoke out.

He spoke out, but he spoke without bitterness. Homage to Catalonia, it must be observed, will provide little nourishment for those who are seeking sensational revelations of Soviet iniquity. Orwell’s original quarrel with the Communists in Spain concerned revolutionary strategy. The Communists, he discovered, were less interested in carrying through a revolution than they were in strengthening Soviet foreign policy. As he put it, with characteristic moderation, ‘The whole of Comintern policy is now subordinated (excusably, considering the world situation) to the defense of U.S.S.R.’

The suppression of the P.O.U.M., therefore, did not altogether shock him, but he was shocked by the false account of the incident that was given to the world. He was a tough-minded person, and he could see that the Communists might feel obliged to eliminate people, including himself, whose ideas about the conduct of the war differed from theirs. What he resented was their saying that he was not a different brand of revolutionary but an agent of Franco.

We know now that the Communist betrayal in Spain was far more heinous than Orwell suspected. To take one example: El Campesino, the peasant general, states in his recent autobiography that the Russians sacrificed Teruel in order to discredit Prieto, the Socialist Minister of Defense. Russian intervention, it is not obvious, has as little to do with idealism as German intervention or Italian. What the Communist would like to have made of Spain is shown by what they have made of the satellite countries since the war. How little they cared for Spanish revolutionaries as revolutionaries is revealed in El Campesino’s grim account of Spanish refugees in Russia.

“But Orwell could not see all this in 1937 and 1938 and, unlike most people who were writing about Spain in those days, he was careful to put down only what he know from firsthand experience. And, as a matter of fact, what he had seen was enough for him. Orwell was a revolutionary, and he knew that revolutions could not be made without bloodshed and misery, but he also knew that no good could come of revolution if truth was one of the victims. It became clear to him in 1937 that the damage the Communists did to men’s bodies was unimportant compared to the damage to their minds. Marveling at the objectivity of Homage to Catalonia, one realizes that there were two Orwells in Spain, the fighter and the thinker, and that somehow they never got in another’s way. All his life he was a man who acted on his convictions without ceasing to subject them to critical scrutiny. That is why V.S. Pritchett, writing in the Book Review when Orwell died, called him ‘the conscience of his generation.’ As Mr. Trilling puts it in his introduction, ‘He was a virtuous man.’

He was honest and courageous and, astonishingly enough, hopeful. He had what sociologist David Riesman has called ‘the nerve of failure.’ In an essay on Arthur Koestler, he wrote: ‘Perhaps some degree of suffering is ineradicable from human life, perhaps the choice of evils, perhaps even the aim of socialism is not to make the world perfect but to make it better. All revolutions are failures, but they are not all the same failure.’ He could look at the worst while he fought for the best. Even the nightmare of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-four is a call to action, not a cry of despair.

Homage to Catalonia begins with a little picture of an Italian volunteer, a man whom Orwell saw only once but who remained in his mind a symbol of the revolutionary spirit. But there is nothing abstract in Orwell’s picture of this man; he is an individual human being, a flesh-and-blood comrade. Not only his companions in the trenches were individuals for Orwell. ‘Curiously enough,’ he wrote at the end of the book, ‘the whole experience has left me with not less belief but more belief in the decency of human beings.’ This was a man, remember, who had nearly lost his life for a cause he had adopted and had been regarded by having his liberty, if not his life, placed in jeopardy. He might well speak of his belief as curious, but we know it was genuine, for he lived by it as long as his life lasted.”

–Granville Hicks, The New York Times, May 18, 1952

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.