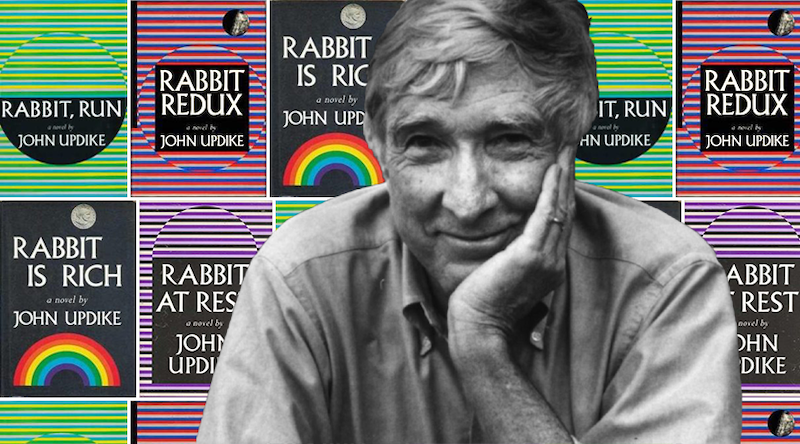

On what would have been the eighty-seventh birthday of John Hoyer Updike—the prolific, double Pulitzer Prize-winning chronicler of the (deep breath) post-war middle class suburban American male psyche—we look back at what the critics first wrote about each of his Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom novels.

Over the course of what is probably the most famous tetralogy in contemporary fiction, Updike’s alter ego goes from being a disaffected 26-year-old former high school basketball star turned salesman in a loveless marriage, to a depressed and overweight grandfather with a drug-addicted son and a bad heart. Along the way there are affairs, flights, births and deaths, health scares, alcoholism, embezzlement, and plenty of extramarital sex.

Angstrom is Updike’s restless American everyman, reappearing at the close of each decade to recap his most recent trials and tribulations against the backdrop of America’s woes. Indeed, taken together, these novels give us not just a portrait of a life, but of the nation as Updike saw it.

*

Rabbit, Run (1960)

You do things and do things and nobody really has a clue.

“This is the stuff of shabby domestic tragedy—and Mr. Updike spares the reader none of the spiritual poverty of the milieu. The old people are listless and defeated, the young noisily empty, the young noisily empty. The novel, nevertheless, is a notable triumph of intelligence and compassion; it has none of the glib condescension that spoils so many books of this type. The characters have an imposing complexity.

…

“The author’s style is particularly impressive; artful and supple, its brilliance is belied by its relaxed rhythms. Mr. Updike has a knack of tilting his observations just a little, so that even a commonplace phrase catches the light. The prose is that rarest of achievements—perfectly pitched voice for the subject.

The treatment of sex commands our attention. For Rabbit, its expression is the final measure of the quality of experience. The author is utterly explicit in his portrayal of Rabbit’s divagations—but the description is as seemly as it is candid, for Mr. Updike is primarily interested in the psychic underside of sexuality. Nevertheless, there are some not-easily-ignored footnotes about the erotic sophistication of the post-war generation that will shock the prudish.

Rabbit, Run is a tender and discerning study of the desperate and the hungering in our midst. A modest work, it points to a talent of large dimensions—already prove in the author’s New Yorker stories and his first novel, The Poorhouse Fair, John Updike, still only 28 years old, is a man to watch.”

–David Boroff, The New York Times, November 6, 1960

Rabbit, Redux (1971)

That’s the trouble with caring about anybody, you begin to feel overprotective. Then you begin to feel crowded.

“There is a great deal in Rabbit Redux, but only because John Updike has put it there. There is more activity than purposefulness: an intricate scheme of parallelisms with the moon shot; a rich (but in the end funked or slighted) sense of possible parallels between oral sex and verbalism or certain verbal habits; likewise a sense of parallels between the job of linotyping and the job of writing. The book is cleverer than a barrel full of monkeys, and about as odd in its relation of form to content. It never decides just what the artistic reasons (sales and nostalgia are another matter) were for bringing back Rabbit instead of starting anew; its existence is likely to do retrospective damage to that better book Rabbit, Run.

…

“Kind at heart, and at head, Updike has qualms about punishment. The only way in which retribution, even when self-inflicted, can be made tolerable to him—especially since he is so implicated with Rabbit, his first great success and always in danger of becoming to his, Updike’s, career what Rabbit’s early success was to Rabbit—is when it is recycled as paying a price. Rabbit, Run never did have to show Rabbit paying a price; he was always allowed to pay with the Monopoly money (he monopolized Updike) of childishness and self-pity. He was always let off at the last minute, and at the very last minute he was allowed to bolt. The rabbit ran; perhaps his desires and his guilts, like fell and cruel hounds, pursued him, but Updike made us avert our eyes and minds in the only thoroughgoing way a writer can: he ended without letting on. It was a great way of letting off. Rabbit Redux ends, weirdly similar, with the sleep of Rabbit and Janice, and proffers this moment out of time and punishment as manifesting some real gain, some new health, some assurance of unflamboyant decency. Rabbit senses her ‘fat’s inward curve’: ‘He finds this inward curve and slips along it, sleeps. He. She. Sleeps. O.K.?’ As an ending it is ingenious and precisely pitched; that rueful sleepy ‘O.K.?’—not for Rabbit to end with ‘Yes I said yes I will Yes’—is to fend off the contrasting sentimentalities of a sigh of relief or of a grimace of dismay.

Nevertheless in so far as we are meant to be at all cheered up by the ending, it cheers me down. Just because Updike has said that behind Rabbit there is Peter Rabbit, that’s no reason for the rest of us to become Flopsy Bunnies. The point is not that no husbands and wives come together with pained hope after lacerating goings-on and adroit cruelties, but that almost the only reason why much hope is on the cards for Rabbit is that Updike very much wants his favored son to have another break. We are to give a more than even break to this particular sucker and suckee.”

–Christopher Ricks, The New York Review of Books, December 16, 1971

Rabbit is Rich (1981)

How can you respect the world when you see it’s being run by a bunch of kids turned old?

“Rabbit Is Rich traces with appalled affection the contours of Rabbit’s maturity: it is about middle-aged spread, physical, mental and (above all) material.

Rabbit has never looked a less likely hero for an American epic. Equipped with a troublesome family and a prosperous car showroom, he is meant to seem provincial and vulgar even by the unexacting standards of suburban Pennsylvania. Rabbit’s reading consists of Consumer Reports and the odd newspaper. His mind is a jabbering mess of possessions, prejudice and pornography. But then Rabbit is an extreme middle-American, a voluble and foul-mouthed representative of the silent majority.

…

“If Rabbit Is Rich has a central theme it has to do with the one-directional nature of life: life, always waiting to be death. Rabbit swans on down the long slide, clumsy, lax and brutish, but vaguely trying.

The technical problem posed by Rabbit is a familiar and fascinating one. How to see the world through the eyes of the occluded, the myopic, the wilfully blind? At its best the narrative is a rollicking comedy of ironic omission, as author and reader collude in their enjoyment of Rabbit’s pitiable constriction. Conversely, the empty corners and hollow spaces of the story fill with pathos, the more poignant for being unremarked.

Being a boor and a goon, Rabbit is on the whole a healthy influence on Updike’s style; but Updike’s style remains a difficulty. In every sense it constitutes an embarrassment of riches—alert, funny and sensuous, yet also garrulous, mawkish and crank. Like Saul Bellow, Updike often seems wantonly, uncontrollably fertile. Here is a writer who can do more or less as he likes.

Furnished with such gifts, a novelist’s main challenge is one of self-contraception. A talent like Updike’s will always tend towards the encyclopaedic. Rabbit Is Rich is a big novel and it would be churlish to wish it any thinner. But it is frequently frustrating. You feel that a better-proportioned book is basking and snoozing deep beneath its covers.”

–Martin Amis, The Observer, January 17, 1982

Rabbit at Rest (1990)

We are each of us like our little blue planet, hung in black space,

upheld by nothing but our mutual reassurances, our loving lies.

“With this elegiac volume, John Updike’s much-acclaimed and, in retrospect, hugely ambitious Rabbit quartet comes to an end. The final word of so many thousands is Rabbit’s, and it is, singularly, ‘Enough.’ This is, in its context, in an intensive cardiac care unit in a Florida hospital, a judgment both blunt and touchingly modest, valedictory and yet enigmatic. As Rabbit’s doctor has informed his wife, ‘Sometimes it’s time.’ But in the nightmare efficiency of late 20th-century medical technology, in which mere vegetative existence may be defined as life, we are no longer granted such certainty.

Rabbit at Rest is certainly the most brooding, the most demanding, the most concentrated of John Updike’s longer novels. Its courageous theme—the blossoming and fruition of the seed of death we all carry inside us—is struck in the first sentence … This early note, so emphatically struck, reverberates through the length of the novel and invests its domestic-crisis story with an unusual pathos. For where in previous novels, most famously in Couples (1968), John Updike explored the human body as Eros, he now explores the body, in yet more detail, as Thanatos. One begins virtually to share, with the doomed Harry Angstrom, a panicky sense of the body’s terrible finitude, and of its place in a world of other, competing bodies: ‘You fill a slot for a time and then move out; that’s the decent thing to do: make room.’

…

“John Updike’s choice of Rabbit Angstrom, in Rabbit, Run, was inspired, one of those happy, instinctive accidents that so often shape a literary career. For Rabbit, though a contemporary of the young writer—born, like him, in the early 1930’s, and a product, so to speak, of the same world (the area around Reading, Pa.)—was a ‘beautiful brainless guy’ whose career (as a high school basketball star in a provincial setting) peaked at age 18; in his own wife’s view, he was, before their early, hasty marriage, ‘already drifting downhill.’ Needless to say, poor Rabbit is the very antithesis of the enormously promising president of the class of 1950 at Shillington High School, the young man who went to Harvard on a scholarship, moved away from his hometown forever and became a world-renowned writer. This combination of cousinly propinquity and temperamental diamagnetism has allowed John Updike a magisterial distance in both dramatizing Rabbit’s life and dissecting him in the process. One thinks of Flaubert and his doomed fantasist Emma Bovary, for John Updike with his precisian’s prose and his intimately attentive yet cold eye is a master, like Flaubert, of mesmerizing us with his narrative voice even as he might repel us with the vanities of human desire his scalpel exposes.

…

“…behind the frenetic activity of the novels, as behind stage busyness, the ‘real’ background of Rabbit’s fictional Mt. Judge and Brewer, Pa., remains. One comes to think that this background is the novel’s soul, its human actors but puppets or shadows caught up in the vanity of their lusts. So primary is homesickness as a motive for writing fiction, so powerful the yearning to memorialize what we’ve lived, inhabited, been hurt by and loved, that the impulse often goes unacknowledged. The being that most illuminates the Rabbit quartet is not finally Harry Angstrom himself but the world through which he moves in his slow downward slide, meticulously recorded by one of our most gifted American realists.”

–Joyce Carol Oates, The New York Times, September 30, 1990

And finally…

“Rabbit Remembered” from Licks of Love (2000)

What’s to say? He was narcissistically impaired, would be my diagnosis. Intuitive, but not very empathic. He never grew up.

“The centerpiece of the book—and the one compelling reason to read it—is a novella-length piece called ‘Rabbit Remembered,’ a sad-funny postscript to Mr. Updike’s quartet of Rabbit novels, which takes up the story of Harry (Rabbit) Angstrom’s family and friends as they try to come to terms with his death and chart the remainder of their own lives.

As in his last Rabbit novel, Mr. Updike writes with fluent access to Harry Angstrom’s world, chronicling the developments in his hero’s small Pennsylvania hometown with the casual ease of a longtime intimate. With compassion and bemused affection, he traces the many large and small ways in which Harry’s actions continue to reverberate through the lives of his widow, Janice, and their son, Nelson, and the equally myriad ways in which their decisions are influenced, consciously or unconsciously, by their memories of him.

…

“As earlier Rabbit installments suggested, Nelson shares many of his father’s traits—a quiet rebel’s defiance, a susceptibility to existential dread and a reluctance to assume the responsibilities of adulthood—and he has also come to repeat many of his father’s mistakes. He, too, has made a hasty, early marriage despite his father’s warnings, and he, too, has stumbled on the unhappy shoals of marital discord.

…

“While these last two stories are touching in their way, Mr. Updike has mined this territory before with considerably more ambition and depth. Indeed these tales only serve to point up the fact that ‘Rabbit Remembered’ is the one piece in this collection that not only reconnoiters old ground but in doing so also manages to transform it into something stirring and new.”

–Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times, November 7, 2000