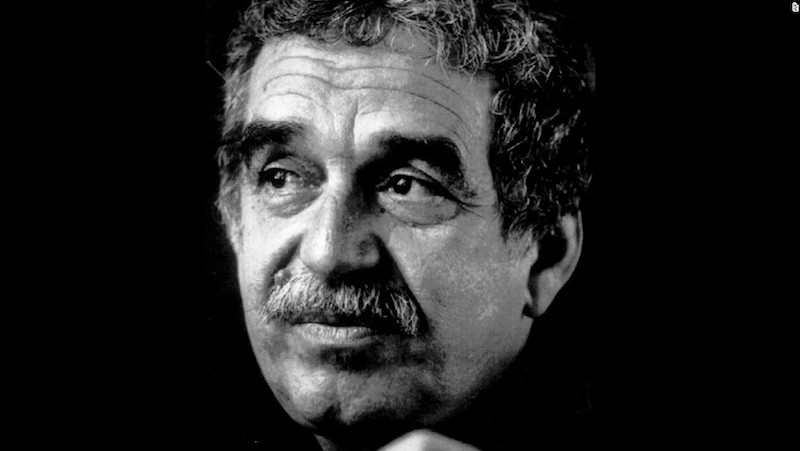

Last week marked four years since the great Colombian magical realist passed away, and the anniversary of his death got us wondering who wrote the first English language reviews of those sweeping, iconic novels. García Márquez was one of the titans of 20th century literature, and by the time his books were translated into English, many of the great authors and critics of the day were queuing up to offer their thoughts on his work. That in mind, we took a look back through the literary criticism archives and found pieces by Thomas Pynchon, Margaret Atwood, Mona Simpson, A.S. Byatt, and more.

*

In Evil Hour (1962)

Shame has poor memory.

“Now in 1979, nearly a quarter of a century after its conception, In Evil Hour appears at last in English, thereby filling in the last significant gap in the García Márquez opus. Given its wit, perception, imaginative richness and easy accessibility, it is astonishing that we have had to wait so long.

Colombia in the mid-1950’s was enmeshed in that seemingly endless epoch of civil wars and bloody repressions known as la Violencia,” which is said to have claimed at least 250,000 lives between 1948 and 1962. The young García Márquez, moving away from the experimental fantasy and lyricism of his early stories toward his own sense of ‘social realism,’ chose to transpose his tale of the lampoons into the contemporary Colombian reality, in this way interlacing a comic craziness with a terrible one.

…

“This air of unfathomable mystery, intensified by García Márquez’s of love of exotic dreams, mad seers’ ghosts and circuses, legends, marvels and comic exaggeration, has caused the Peruvian critic and novelist Mario Vargas Llosa to declare in his History of a Deicide (an exhaustive and seminal but as yet untranslated study of García Márquez’s work) that although ‘the victory of the imaginary. . .is here so subtle, so disguised, that to many critics In Evil Hour seems like the most ‘realistic’ of all García Márquez’s books,’ it is, excluding the earliest stories, ‘the first “fantastic” text that he has written.’

The truth is, though, that the conflict in this book between the ‘realistic’ and the ‘fantastic’ is never adequately worked out. The mysterious, almost magical, lampoons are at the very heart of the plot, yet the final state of affairs, brought on by the clandestine political fliers and the boy’s murder, has almost nothing to do with them. It’s like two stories overlaid on each other but not yet interlaced.”

–Robert Coover, The New York Times, November 11, 1979

“First published in Spain in 1968—so a forebear of One Hundred Years of Solitude, G-M’s benchmark—and set also in a small jungle town, this short friendly novel weaves much less exaggerated fantasy than OHYS, but shares the same calm yet gay prose and morose humor. ‘Lampoons’ have begun springing up on walls around town at night, misspelled gossip sheets that ‘say what everybody knows, which is almost always sure to be the truth.’ Not that anyone ever really sees them; they’re ripped down too fast. But each poor soul is nervously afraid that the next one will be about him or her. Sailing imperturbably through the uproar are the local priest, the local doctor and dentist (a leader of the clandestine opposition to the corrupt regime of the military mayor), and his less-than-excellency himself. Eventually the story sharpens to a political point about corruption, but it’s all done with genial exactitude; ‘Don’t be surprised,’ one character reassures another, ‘all of this is life.’ Not major work but—again gloriously served by a fine Gregory Rabassa translation (‘While the doctor was studying the dial, the curate examined the room with that boobish curiosity that consulting rooms tend to inspire’)—a pleasing glimpse of a fanciful, vivid imagination at its most unforbidding.”

–Kirkus Reviews, October 1, 1979

*

One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967)

Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice…

“This extraordinary novel obliterates the family tree in a prose jungle of overwhelming magnificence … Above all, García Márquez (via his translator) feeds the mind’s eye non-stop, so much so that you soon begin to feel that never has what we superficially call the surface of life had so many corrugations and configurations, so much bewilderingly impacted detail, or men so many grandiose movements and tics, so many bizarre stances and airs.

…

“Let it be said that, although the man’s sentences are immaculately built, the vision they contain is violent and lurid enough to make the works of two better-known Latin Americans, J. L. Borges and Julio Cortázar, look (respectively) mincing and pretty.

…

“It’s a prose that’s always controlled, but it expresses a vision full of lunges, spurts, mild or maniacal hallucinations, preternatural heavings and bulging gargoyles. Tracing the growth of Macondo, García Márquez is rather like an infatuated god watching a planet seethe and bubble, settle and cool, and then develop forms of life that finally annihilate themselves. The town, of course, is made of prose, as is the ever-encroaching jungle; and, such is the prose’s dense physical immediacy, you have the sense of living along with the Buendías (and the rest), in them, through them, and in spite of them, in all their loves, madnesses and wars, their allegiances, compromises, dreams and deaths.

…

“The verbal Mardi Gras which is his mode of narrating invokes a before and an after (birth and death), which no hyperboles, his or ours, can alter. Like the jungle itself, this novel comes back again and again, fecund, savage and irresistible.”

–Paul West, The Washington Post, February 22, 1970

“One has only to read a few pages of Márquez’s novel to understand the response it has occasioned. Immediately, the reader senses in its style a simple audaciousness which alerts him to the premise that he is attending to something more than an ordinary chronicle of fiction, that he is being presented, rather, with a work that presumes nothing, that starts from a beginning both in literary and historical time, as if existence itself had no previous records or memories.

…

“Cien años de soledad may indeed be a depiction of a time and a culture, but Márquez also makes it clear that his tale is more a dream of art than a collection of social and historical truths, and, at the work’s end, when this dream takes on the force of a metaphor for all the cycles of human life that have vanished, one realizes that the excellence of this book lies in its victory over the quaint and anecdotal, in its sustained vision of the vanities and futile passions with which humanity tries to forestall its fate of being, in art and actuality, comically impermanent.

…

“Márquez forces upon us at every page the wonder and extravagance of life, while compassionately mocking its effusions; and when the book ends with its sudden self-knowledge and its intimations of holocaust, we are left with that pleasant exhaustion which only very great novels seem to provide; for they allow us, in a moment of exquisite balance, to hold a vision—to be sure, in some fear, but also with humor—of the beginnings and ends to all the enterprises of living. Márquez, with his tale of Macondo and the Buendías, strikes such a balance and makes us feel as if we had survived his century of articulate dreams only to awaken and discover that they must finally all come true.”

–Jack Richardson, The New York Review of Books, March 26, 1970

*

The Autumn of the Patriarch (1975)

…the bells of glory that announced to the world the good news that the uncountable time of eternity had come to an end…

“He has added to these times of his own life fragments from the long history of dictators—the deaths of Julius Caesar and Mussolini, the durability of Stroessner, the wife-worship of Perón, what seems to be a close study of the times of Trujillo and the United States and English gunboat-puppeteering of so many bestial morons into the dictator’s palace. He has absorbed and re-imagined all this, and more, and emerged with a stunning portrait of the archetype: the pathological fascist tyrant.

…

“The novel is unendingly bizarre and fevered, but ultimately not difficult. Yet it is difficult to enter: a densely rich and fluid pudding that begins at the end and makes Faulknerian leaps forward and backward in time. Sentences at times run on for three pages, with dialogue neither quoted nor paragraphed. García Márquez has compounded the problems by making the novel a puzzle of pronouns, consistently changing narrative points of view in mid-sentence.

The narration is largely within the General’s mind, but García Márquez also enters other minds with brief intensity, often speaks in the collective voice of all people in the blasted nation; and so, through relentless immersion of the reader in these exquisitely detailed perspectives, he illuminates the monster internally and externally and delivers him whole.

…

“A reader grows somewhat weary at times over the excesses, the repetition and predictability of certain sections—that old man walking endlessly through the palace corridors, kicking lepers and beggars in the courtyard, tending the resident cows on the stairs and taking the concubines by surprise, and there is a yearning for some pithy understatement. But García Márquez is as exorbitant as Melville and Dostoyevsky. He believes not only that excess is good for you, but that it is essential, that a book must have an immensity about it in the same way life is enormous—and dense and mysterious and as repetitiously predictable as the General’s vengeance for an affront. How else, his novel implicitly asks, could the story of interminable dictatorship be told?

This novel, of necessity then, has none of the life-celebrating quality that made One Hundred Years of Solitude so universally embraced. There is nothing to celebrate in the General’s long and tortured life. He is given endless opportunity to persuade us that his anguish and grief and bafflement are real. But we are never persuaded. He is not even pitiable. He is a spectacle, the embodiment of egocentric evil unleashed, maniacally violent, cosmically worthless and despite pretentions to eternity, as devoid of meaning as anything else in an absurd world. His main contribution to life, finally, is fear; but fear such as thunder, cancer or madness may provoke, fear based on irrational possibility, on the oblique ravages of a diabolical deity.

The book is a supreme polemic, a spiritual exposé, an attack against any society that encourages or even permits the growth of such a monstrosity.”

–William Kennedy, The New York Times, October 31, 1976

“Garcia Marquez’ patriarch is mythical, having sired 5000 children and grown a third set of teeth at the age of 150. Story follows story of his regime, a “stew of destruction,” and of those closest to him: his favorite, the General, who ended up on a silver tray stuffed with pine nuts and herbs; or his mother mourned until his own dying–that innocent peasant mother who painted bird pictures, orioles; or his only spouse, Leticia, the novice he kidnapped from a convent and imported in a crate marked ‘fragile. . . this side up.’ Leticia educated and refined him and was destroyed, with their son, by killer dogs. The vertigo of images and scenes matches the momentum of those sentences, those ever-ongoing sentences, pages at a clip, which suggest an eternity of days and years. Read it as a magnification of fable, or as violent grand guignol, or as political allegory of a world which defies and stops time, much as the patriarch attempted to; read it as a canticle to the ‘miseries of glory’ and mortality, remembering that ‘the most feared enemy is within oneself’; read it as a dazzling work of imaginative conjure; read it. . . ”

–Kirkus Reviews, November 1, 1976

*

Love in the Time of Cholera (1985)

Florentina Ariza had kept his answer ready for fifty-three years, seven months and eleven days and nights. “Forever,” he said.

“Suppose it were possible, not only to swear love ‘forever,’ but actually to follow through on it—to live a long, full and authentic life based on such a vow, to put one’s alloted stake of precious time where one’s heart is? This is the extraordinary premise of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s new novel Love in the Time of Cholera, one on which he delivers, and triumphantly.

…

“He writes with impassioned control, out of a maniacal serenity: the Garcimarquesian voice we have come to recognize from the other fiction has matured, found and developed new resources, been brought to a level where it can at once be classical and familiar, opalescent and pure, able to praise and curse, laugh and cry, fabulate and sing and when called upon, take off and soar.

…

“…in this novel we have come a meaningful distance from Macondo, the magical village in One Hundred Years of Solitude where folks routinely sail through the air and the dead remain in everyday conversation with the living: we have descended, perhaps in some way down the same river, all the way downstream, into war and pestilence and urban confusions to the edge of a Caribbean haunted less by individual dead than by a history which has brought so appallingly many down, without ever having spoken, or having spoken gone unheard, or having been heard, left unrecorded. As revolutionary as writing well is the duty to redeem these silences, a duty Garcia Marquez has here fulfilled with honor and compassion. It would be presumptuous to speak of moving ‘beyond’ One Hundred Years of Solitude but clearly Garcia Marquez has moved somewhere else.

…

“There is nothing I have read quite like this astonishing final chapter, symphonic, sure in its dynamics and tempo, moving like a riverboat too, its author and pilot, with a lifetime’s experience steering us unerringly among hazards of skepticism and mercy, on this river we all know, without whose navigation there is no love and against whose flow the effort to return is never worth a less honorable name than remembrance -at the very best it results in works that can even return our worn souls to us, among which most certainly belongs Love in the Time of Cholera, this shining and heartbreaking novel.”

–Thomas Pynchon, The New York Times, April 10, 1988

“It is hard now to recover the thrill of underground discovery, the hand-to-hand ardour, the feeling of claim engendered by A Hundred Years of Solitude. But Love in the Time of Cholera, like Autumn of the Patriarch before it, gives us something altogether new. With gorgeous, lucent writing, full of brilliant stops and starts, majestic whirls, thrilling endings, splendour and humor, the magician of our century takes on psychological realism.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez tells his stories with a strange omniscience. He is as capable of seeing the dignity in homeliness and poverty as the hidden jokes and rituals of opulence, as comfortable with science, magic, voodoo, ghosts, as with the riddles of Catholicism. The sources of his omniscience seem to be lodged not in any moral or political system, but rather in time – his voice holds the perspective any sensible person would have, given an easy sliderule to the future. And if Time and History are impartial, or impartial to the fate of individuals, so is Garcia Marquez.

…

“This pace, this level of realism, tends towards metaphor rather than allegory. We never quite lose life, life in our world, the way we could in Macondo. This is, of course, a loss and a gain. The intrusion of reality, however, allows for majestic psychological revelations which would have been completely impossible in Macondo.

…

“In Love in the Time of Cholera, the proportion of Marquesian plot to character has radically changed. He still introduces thousands of plots, traditional and idiosyncratic, from the most predictable to the sublime, but they only hover around the central characters.

…

“Garcia Marquez has written before about poverty and about riches – a brilliant early story, ‘Tuesday Siesta’, about the dignity of the poor in the face of sleepy convention comes to mind – but he has never before taken on the psychology of yearning, the thwarting character of the desire for more. Here he writes, ruefully and comically: ‘In those days, being rich had many advantages, and many disadvantages as well, of course, but half the world longed for it as the most probable way to live for ever.’ In Macondo, people did live for ever. In Love in the Time of Cholera, their wistful collective desire tells us a great deal about the internalised longings born of class inequality.

…

“They are not immune to history. And they are old. Florentino Ariza is bald. The first night of romance, Fermina Daza sends him away, saying: ‘Not now, I smell like an old woman.’ But they are not merely products of personal and public history. ‘Both were lucid enough to realise, at the same fleeting instant, that the hands made of old bones were not the hands they imagined before touching. In the next moment, however, they were.’ Garcia Marquez has brought a new depth to the meaning of the word ‘magic’.”

–Mona Simpson, The London Review of Books, September 1, 1988

*

The General In His Labyrinth (1989)

Freedom is often the first casualty of war

“Had [Simon] Bolivar not existed, Mr. Garcia Marquez would have had to invent him. Seldom has there been a more fitting match between author and subject. Mr. Garcia Marquez wades into his flamboyant, often improbable and ultimately tragic material with enormous gusto, heaping detail upon sensuous detail, alternating grace with horror, perfume with the stench of corruption, the elegant language of public ceremony with the vulgarity of private moments, the rationalistic clarity of Bolivar’s thought with the malarial intensity of his emotions, but tracing always the main compulsion that drives his protagonist: the longing for an independent and unified South America. This, according to Bolivar himself, is the clue to all his contradictions.

Just now, when empires are disintegrating and the political map is being radically redrawn, the subject of The General in His Labyrinth is a most timely one. It is noteworthy that Mr. Garcia Marquez has chosen to depict his hero not in the days of his astonishing triumphs, but in his last months of bitterness and frustration. One feels that, for the author, the tale of Bolivar is exemplary, not just for his own turbulent age but for ours as well. Revolutions have a long history of eating their progenitors.

…

“The structure of the book is itself labyrinthine, turning the narrative back on itself, twisting and confusing the thread of time until not only the general but the reader cannot tell exactly where or when he is. Woven into the present, as memory, reveries, dream or feverish hallucination, are many scenes from the general’s earlier life: near catastrophes in war, splendid triumphs, superhuman feats of endurance, nights of orgiastic celebration, portentous turns of fate and romantic encounters with beautiful women, of which there seem to have been a large number.

…

“In addition to being a fascinating literary tour de force and a moving tribute to an extraordinary man, The General in His Labyrinth is a sad commentary on the ruthlessness of the political process. Bolivar changed history, but not as much as he would have liked. There are statues of ‘The Liberator’ all over Latin America, but in his own eyes he died defeated.”

–Margaret Atwood, The New York Times, September 16, 1990

“…the novel can’t do much more than prowl around Bolivar, hooked as it is on the enigma of his behaviour. It seeks to portray the enigma, not to end it, and thus becomes a picture not so much of a historical figure as of a terminal mood, the bafflement of a man who has become a ghost too soon.

…

“In some respects Garcia Marquez’s Bolivar resembles Colonel Aureliano Buendia in One Hundred Years of Solitude, in other respects the bewildered tyrant of Autumn of the Patriarch. But most of all he resembles a bit-player who crops up again and again in Garcia Marquez’s fiction, the man who gets lost in the rain and in history (or in one story, lost in time). Bolivar is literally seen here as ‘lost in the rain’, perdido en la lluvia. The rain haunts the novel like a signature, becomes ‘eternal’, represents weather which ‘would not clear for the rest of the century’. The drizzle looks like an image of endless doubt, and getting lost is the story which swallows all other stories, the voracious metaphor which won’t let them escape.

Bolivar is not just uncertainty but certainty gone astray, and all the political thought in the novel seems subordinate to this metaphysical lapse…Of course, we shouldn’t expect an argument from Bolivar, but the absence of political interest on Garcia Marquez’s part is striking. He seems too taken with what he calls in a note ‘the horror of this book’.

There is the horror of death and neglect, very well rendered in the novel’s last paragraph: ‘He examined the room with the clairvoyance of his last days, and for the first time he saw the truth: the final borrowed bed, the pitiful dressing-table whose clouded, patient mirror would not reflect his image again, the chipped porcelain washbasin with the water and towel and soap meant for other hands, the heartless speed of the octagonal clock …’ I need to stop the quotation here before it slides into the sentimentality of an ‘ineluctable appointment’ with death. ‘Heartless’ is already reaching for the easy pathos. But the horror is not only the miserable truth, the decrepit destiny. It lies also in the possibility that Bolivar may not have a destiny, that there never was a historical face in the patient mirror, only the mug of a man of talent, courage and a wild, obsessive idea. Garcia Marquez hints at this thought, but even he is not about to explore it.”

–Michael Wood, The London Review of Books, January 24, 1991

*

Of Love and Other Demons (1994)

Do not allow me to forget you.

“Is it to avoid directly engaging his urgent political beliefs that Marquez refuses to set his work in the contemporary world? Today’s politics is for journalism, his career would seem to suggest; in fiction he prefers to speak through the freeing, illusory distance of half a century or more. One Hundred Years begins practically at the dawn of time. The uneven Love In the Time of Cholera takes place near the turn of the century. The General in His Labyrinth, a masterpiece of historical fiction, depicts the liberator Simon Bolivar in the final year of his life, a disillusioned soldier besieged by betrayal, greed, arthritis, and chronic gloom.

Of Love and Other Demons does not depart from this pattern. Set in colonial times in a major Caribbean slave and mineral port reminiscent of Marquez’ own Cartagena, the book manages in its short length to juxtapose the Catholic superstition of devil possession with the Yoruban rituals of West Africa, and with the precepts of European Enlightenment in the guise of a learned Jewish physician.

…

“Despite this intriguing story (attributed, again, to one of his grandmother’s tales) Demons is not nearly as focused as Marquez’ earlier novella Chronicle of a Death Foretold, whose complex construction offered much to admire. At 150 pages, Demons suffers from a somewhat lopsided structure. With its large and diverse cast one can easily see this book running 300 pages, or, conversely, being trimmed of some characters and telescoped into a story half its current size. As it stands, near the end Marquez must resort to a too-rapid shorthand.

…

“But there are many glimmering moments. Historical details are woven superbly into the text, and most of the time the author’s eye is as capable and intelligent as ever. Oddly, the supernatural fancies that are his trademark often feel unnecessary here, perhaps because his imitators have already turned them into clichs. As it happens, those ‘magical’ strokes are not what make Marquez great, but rather his uncanny linguistic prowess, with its empathic and revelatory wisdom.”

…

“Marquez’ fluency and inventiveness are undiminished, despite the occasional wheeze of impatience that has crept into his prose. He’s in a rare stratosphere, one of the finest writers of the second half of our century, and the rewards of his fiction— old and new—are vast.”

–Michael Greenberg, The Boston Review, Summer 1995 Issue

“The world is the familiar Garcia Marquez world, a mixture of phantasmagoria and a realism whose truths seem as incredible and strange as the moments of demonic magic. The tale—spare and swift in the telling—has all the ineluctable, irrational fatality of Chronicle of a Death Foretold, though the love story, also grim and driven, has none of the comic and inconsequential gentleness of Love in the Time of Cholera.

…

“What are the real demons of the title?

They are legion, and include love. The Bishop (a wonderful portrait of a dying, powerful man who is asthmatic and out of his culture) sees rabies as a form that the demon may take to enter an innocent body. The superstitious abbess to whom Sierva Maria is entrusted finds something supernatural and portentous in every ordinary event; the fact that she did not notice the girl’s presence in her courtyard for several hours (Sierva Maria blended in among her natural people, the slaves) meant to her that the girl must have been rendered invisible by witchcraft…Yet it is completely clear, not for the first time in Mr. Garcia Marquez’s fiction, that the real forces of destruction are the beliefs of the Spanish and the Christians.

…

“Sierva Maria’s martyrdom at the hands of ignorant superstition has the ambiguous attributes of sanctity and demonic possession: filth, sores, huge areas of stinking excrement—the physical side of the human being driven out, extruded. Seen in this context, her beautiful cloak of shining hair, shaved for the exorcism only to sprout with fantastic life-in-death in her grave, is a shapeshifter’s pelt, her animal vitality, her sexuality, the life of which her father is so afraid. But hair is dead matter, a form of excrement. Mr. Garcia Marquez’s pointed and resonant epigraph is from St. Thomas Aquinas’s treatise On the Integrity of Resurrected Bodies: ‘For the hair, it seems, is less concerned in the resurrection than other parts of the body.’

What is body and what survives? What is flesh and what is spirit and what is demonic? Mr. Garcia Marquez’s answer is an almost didactic, yet brilliantly moving, tour de force.”

–A.S. Byatt, The New York Times, May 28, 1995