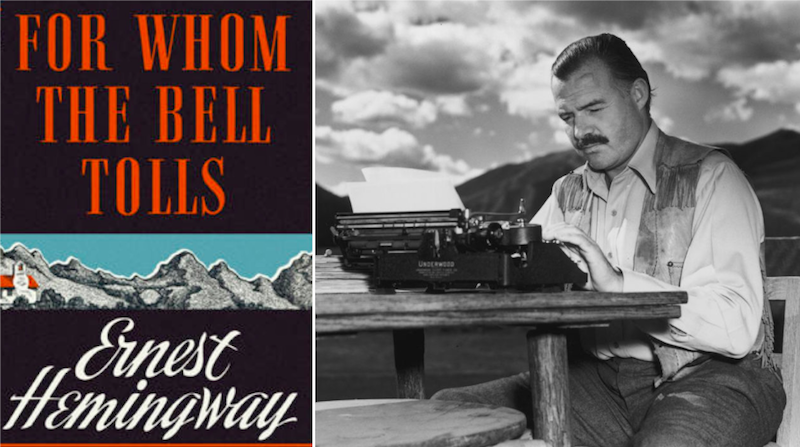

Today marks the 80th publication anniversary of Ernest Hemingway’s Spanish Civil War epic, For Whom the Bell Tolls. The story a young American volunteer fighting with a Republican guerrilla unit against Franco’s fascist forces, the novel—which drew on the author’s own experiences as a reporter for the North American Newspaper Alliance during the war—was a huge critical and commercial triumph for Hemingway, selling half a million copies in its first few months.

For Whom the Bell Tolls was also a finalist for the 1941 Pulitzer Prize, allegedly chosen as the winner by both the jury and the board, before being vetoed by Columbia president (and ex-officio chairman of the board) Nicholas Murray Butler because he found the book offensive.

In 1943, less than two years after the book was first published, Paramount Pictures released a wildly successful movie adaptation of the book staring Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman, both of whom, somewhat incredibly, were handpicked for their roles by Hemingway himself.

To mark this Oak Anniversary, we’re talking a look back at one of the earliest reviews of “the first major novel of WWII.”

“The world is a fine place and worth fighting for and I hate very much to leave it.”

*

“All that need be said here about the new Hemingway novel can be said in relatively few words. For Whom the Bell Tolls is a tremendous piece of work. It is the most moving document to date on the Spanish Civil War, and the first major novel of the Second World War.

As a story, it is superb, packed with the matter of picaresque romance: blood, lust, adventure, vulgarity, comedy, tragedy. For Robert Jordan, the young American from Montana, the lust and adventure are quickly drowned in blood. The comedy, as in other Hemingway fiction, is practically indistinguishable from the vulgarity, which in this case is a rich and indigenous peasant brand. The tragedy is present and only too plain; the bell that began tolling in Madrid four years ago is audible everywhere today.

“Robert Jordan is a partizan attached to the Loyalist forces. He is neither a professing Communist nor a professional soldier, but a college instructor who happened to be in Spain on sabbatical leave. During the three or four days covered by the story, he hides out in Franco-controlled territory, into which he has been sent by headquarters to dynamite a strategic mountain bridge.

He doesn’t hide out alone; as prearranged, he has made contact with a certain guerrilla band operating from a cave high in the Sierra de Guadarrama. He meets two women there, one middle-aged and as tough and blasphemous as any man, the other young and frightened, her hair still short because the Falangists shaved it off after they shot her parents and rampaged through her native town.

“He meets the saturnine Pablo, who sits in the cave half drunk and mumbles, ‘Thou wilt blow no bridge here.’ He meets old Anselmo, who helps him blow it in the end, and Primitivo, Fernando, Augustin and several more. Once he meets El Sordo, who lives with his band on another ridge some miles way. ‘Listen to me,’ El Sordo explains, ‘we exist here by a miracle. By a miracle of laziness and stupidity of the Fascists which they will remedy in time. Of course we are very careful and we make no disturbance in these hills.’

But Robert Jordan has come to make a disturbance. He must make it if the Loyalist drive out of Madrid toward Segovia is to have a chance to succeed.

“Mr. Hemingway has always been the writer, but he has never been the master that he is in For Whom the Bell Tolls. The dialogue, handled as though in translation from the Spanish, is incomparable. The characters are modeled in high relief. A few of the scenes are perfect, notably the last sequence and an earlier one when Jordan awakes to the sound of a horse thumping along through the snow. Others are intense and terrifying, still others gentle and almost pastoral, if here and there a trifle sweet.

It is fourteen years since The Sun Also Rises and eleven since A Farewell to Arms. More than three hundred years ago John Donne said, ‘No man is an Iland, intire of it selfe; every man is a peece of the Continent, a part of the maine. And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.’ Mr. Hemingway has taken this text and, out of his experiences, convictions and great gifts, built on it his finest novel.”

–Ralph Thompson, The New York Times, October 21, 1940

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.