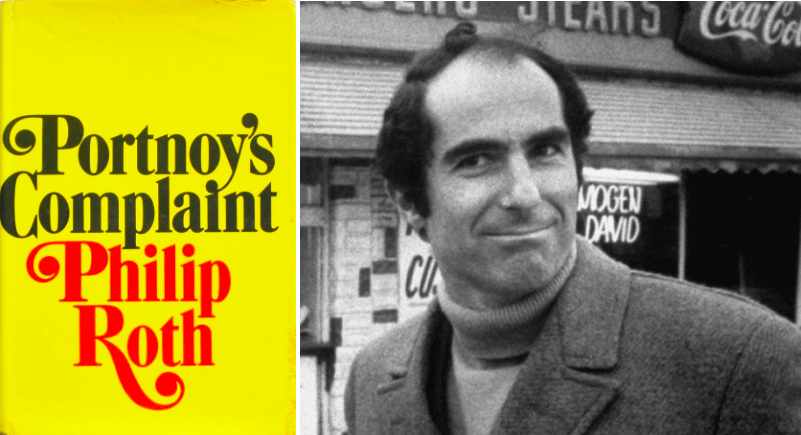

Upon its release in 1969, Portnoy’s Complaint—Philip Roth’s notorious novel of “a lust-ridden, mother-addicted young Jewish bachelor” confessing his sexual desires and frustrations to a silent psychoanalyst—caused a firestorm of controversy and catapulted its young author to literary celebrity. Some critics deemed it obscene and anti-Semitic, others lauded it as a a moving and uproarious tour-de-force. Either way, the book certainly got people talking and its renown has now endured for over half a century.

In honor of the its 52nd publication anniversary, we thought we’d take a look back through the archives at some of the first responses to the novel the New Yorker greeted as “one of the dirtiest books ever published.”

*

“I am marked like a road map from head to toe with my repressions. You can travel the length and breadth of my body over superhighways of shame and inhibition and fear.”

*

“Guilt-edged insecurity is far more important when it comes to the making—and unmaking—of an American Jew than, say, chicken soup or chopped liver. For guilt is as traditionally American as Thanksgiving Day pumpkin pie and, at the same time, on native grounds as far as Jews are concerned: it was the Jews who originated that mother lode of guilt, the theological concept of original sin; it was a Jew who developed psychoanalysis, that clinical faith based on a belief in the transferability and negotiability of long-term debts and credits in guilt.

So, not surprisingly, a special blend of guilt-power usually fuels the American-Jewish character in fiction, sends him soaring to his manic highs and plummeting to his abject lows. Whether it is Salinger’s Seymour or Bellow’s Herzog or Malamud’s Assistant (who, in fact, becomes a Jew just because of his guilt), almost formula-like the American-Jewish hero goes forth to confront the twisted root-causes of his guilt—only to flood his engine with the paralyzing second thoughts of the self-tormenting neurotic, the fringe-level psychotic. For unable to live with his guilt, he is also unable to conceive of living without it.

But while the American-Jewish novelist has thus had a subject, though he has been searching diligently, questing imaginatively, he has lacked an ideal form. Now, with Portnoy’s Complaint, Philip Roth (Goodbye Columbus, Letting Go, When She Was Good) has finally come up with the existentially quintessential form for any American-Jewish tale bearing—or baring—guilt. He has done so by simply but brilliantly casting his American Jewish hero—so obviously long in need of therapy—upon a psychoanalysts’s couch (the current American-Jewish equivalent of the confessional box) and allowed him to rant and rave and rend himself there. The result is not only one of those bullseye hits in the ever-darkening field of humor, a novel that is playfully and painfully moving, but also a work that is certainly catholic in appeal, potentially monumental in effect—and, perhaps more important, a deliciously funny book, absurd and exuberant, wild and uproarious.

…

if by this definitive outpouring into a definitive vessel of a recurring theme, thus guilt (screaming, strident, hysterical, hyperbolic, hyperthyroid) has been successfully expatiated, and future American-Jewish novels will be all the quieter, subtler, more reflective and reasoned because of it, then this novel can truly be judged a milestone. For guilt in esthetic terms is every bit as debilitating and destructive and time-consuming a hang-up as in behavioral terms. And it is only by moving out beyond guilt, to the problems and turf implicit in adult independence and sovereignty, that any literature—or genre—can hope to begin to approach maturity.

But meanwhile, whether a dead-end auto-da-fé or open-end bar mitzvah peroration (and not just ‘Today I am a penis’) on the road to cultural manhood—read Portnoy’s Complaint. And don’t feel the least bit guilty about enjoying it thoroughly: I know not since Catcher in the Rye have I read an American novel with such pleasure.”

–Josh Greenfeld, The New York Times, February 23, 1969

*

“…his book is farce with a thesis. The burden of Portnoy’s fiercely funny self-revelation is that all his sexual difficulties derive from the guilt imposed on him in his upbringing. It is guilt that made Portnoy the athletic and ingenious masturbator that Mr. Roth shows him to have been in his boyhood, and it is guilt that makes him impotent with all except Gentile girls when he comes to manhood—after various amorous misadventures among the Wasps, his author leads Portnoy to ritual slaughter in Israel. The prime purveyor of this guilt is, we see, his Jewish mother, who has ladled out injunction and precept, sometimes at the point of a knife, with every mouthful of nourishment she inflicts on her defenseless child—Portnoy’s father is indictable chiefly as an example of male capitulation to the Jewish female principle. The clue to Portnoy’s rage at the pass to which he has been brought lies in the word ‘imposed.’ Just as we have no choice in the selection of our parents, just so, according to Mr. Roth, we have no choice but to receive the guiltiness they inculcate in us. Portnoy has no responsibility for being the person he is. He has simply, inevitably, incorporated all the inhibiting lessons taught him in his early years. How, as the product of this death-dealing instruction, Mr. Roth’s protagonist has achieved his sexual freedom at least with Gentile girls—and it is considerable: there are Gentile readers who might envy him—Mr. Roth doesn’t tell us. He also doesn’t explain where, other than from his training in guilt, Portnoy learned the contempt for his own sexual behavior which makes the basis for his condemnation of his parents.

…

“In the view of Mr. Roth, guilt is only and always an alien substance in the human composition, introduced for the destruction of our joy and the perpetuation of old sorrows. And because guilt intervenes so grossly between us and our full individual humanity, it necessarily incapacitates us in our relations with other people, especially the relation between the sexes. And this is of course why the Jewish condition, so supremely guilt-laden, is now thought to offer literature its best material for describing the whole modern human condition—the alienated Jew is our most cogent instance of alienated modern man.”

–Diana Trilling, Harper’s, 1969

*

“The cruelest thing anyone can do with Portnoy’s Complaint is to read it twice. An assemblage of gags strung onto the outcry of an analytic patient, the book thrives best on casual responses; it demands little more from the reader than a nightclub performer demands: a rapid exchange of laugh for punch-line, a breath or two of rest, some variations on the first response, and a quick exit. Such might be the most generous way of discussing Portnoy’s Complaint were it not for the solemn ecstasies the book has elicited, in line with Roth’s own feeling that it constitutes a liberating act for himself, his generation, and maybe the whole culture.

…

“The controlling tone of the book is a shriek of excess, the jokester’s manic wail, although, because it must slide from skit to skit with some pretense of continuity, this tone declines now and again into a whine of self-exculpation or sententiousness. And the controlling sensibility of the book derives from a well-grounded tradition of feeling within immigrant Jewish life: the coarse provincial ‘worldliness’ flourishing in corner candy-stores and garment centers, at cafeterias and pinochle games, a sort of hard, cynical mockery of ideal claims and pretensions, all that remains to people scraped raw by the struggle for success.

…

“Portnoy’s Complaint is not, as enraged critics have charged, an anti-Semitic book, though it contains plenty of contempt for Jewish life. Nor does Roth write out of traditional Jewish self-hatred, for the true agent of such self-hatred is always indissolubly linked with Jewish past and present, quite as closely as those who find in Jewishness moral or transcendent sanctions. What the book speaks for is a yearning to undo the fate of birth; there is no wish to do the Jews any harm (a little nastiness is something else), nor any desire to engage with them as a fevered antagonist; Portnoy is simply crying out to be left alone, to be released from the claims of distinctiveness and the burdens of the past, so that, out of his own nothingness, he may create himself as a ‘human being.’ Who, born a Jew in the 20th century, has been so lofty in spirit never to have shared this fantasy? But who, born a Jew in the 20th century, has been so foolish in mind as to dally with it for more than a moment?”

–Irving Howe, Commentary Magazine, December 1, 1972

*

“In Portnoy’s Complaint, Philip Roth has made the Grave Admission that he does care, that the tender emotions of small Jewish boys are not protected from the psychic inconvenience of being different. That Moses and Abraham are really not all that effective at the job of protection they’re supposed to be doing. Too bad, Moe and Abe, but Henry Aldrich didn’t talk to me today and somehow I don’t feel like hanging around waiting for YOU, either. Too bad.

When you come to think about it, this admission of Roth’s is not so startling, the admission that one can be slightly unstrung by the simple condition of ‘not fitting in,’ the simple condition of belonging to a family or people which has been given this condition—the condition of not quite fitting in—to carry around like a cross or something. In fact…this is an admission? Couldn’t anybody have figured it out by themselves?

Somehow not. Somehow nobody has both figured it out and laid it out, naked and tragic-comic, as Philip Roth has in this book about Alexander Portnoy, the ostensibly successful Jewish lawyer from Newark. Portnoy, in the book, is dredging up his childhood and youth, from the fearsome discovery of his mother’s persona to his obsessive discovery of sex—and beyond to the life (and sex life) of the man.

…

“The ‘obscenity’—clinical descriptions of masturbation and more social forms of sex—is something that will astonish readers in direct proportion to their unfamiliarity with the other terrain. In other words, it’s quite a mountain if you can’t make out the rest of the range. With Portnoy, plenty of people will miss the context.

And maybe that is one of the most interesting things about Portnoy—the division between those who get it, for any number of reasons, and those who don’t, for reasons just as numerous and diverting.”

-Mort Persky, The Detroit Free Press, April 13, 1969

*

“There are two voices in Portnoy’s Complaint, Philip Roth’s quasi-autobiographical tour de force, though both voices are the voices of the hero. The truer one is best represented by the remarkable section called ‘Jewish Blues.’ Here the theme is adolescent rage, middle class New Jersey misery, and filial ambivalence (‘a Jewish man with parents alive is a 15-year-old boy, and will remain a 15-year-old boy till they die!’). The tone is at once nostalgic and embittered, rollicking and sad, and the juxtaposition of domestic conventions with the wild masturbatory fantasies of young Alex Portnoy, achingly accurate in every respect, including the highly colored one of the ‘castrating’ Jewish mama, often equals the pathetic brilliance of some of the short stories of Gogol and Babel, besides being, in its rather idiosyncratic way, a closer look at the ‘generation gap’ than anything that has yet appeared in print. The other voice, while rarely losing its original verve, (this is, without doubt, the most ‘inspired’ of Roth’s performances), is much less authentic or agreeable … Masterful in parts, phony in others, but obviously a ‘hot’ best-seller.”

–Kirkus Reviews, February 1, 1968