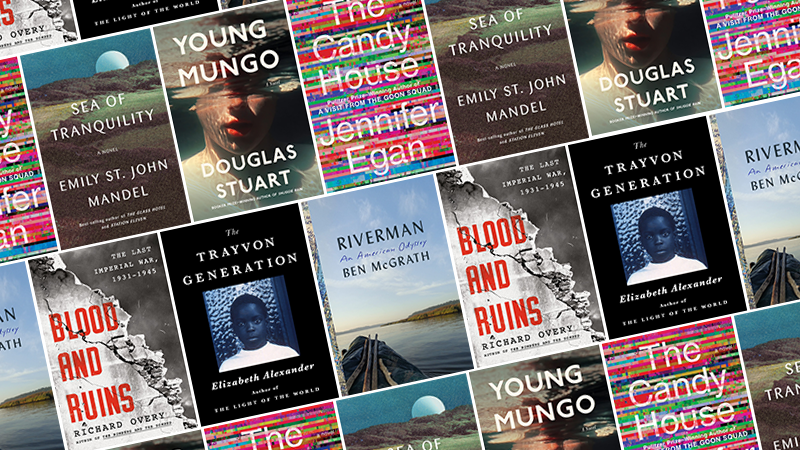

Douglas Stuart’s Young Mungo, Jennifer Egan’s The Candy House, Emily St. John Mandel’s Sea of Tranquility, Richard Overy’s Blood and Ruins, Elizabeth Alexander’s The Trayvon Generation, and Ben McGrath’s Riverman all feature among the best reviewed books of the week.

*

1. Douglas Stuart, Young Mungo

(Grove Press)

16 Rave • 3 Positive • 2 Mixed

“Stuart writes like an angel … masterful … if Stuart has not departed much from the scaffolding of his debut novel, he has managed to produce a story with a very different shape and pace … The raw poetry of Stuart’s prose is perfect to catch the open spirit of this handsome boy, with his strange facial tics … The way Stuart carves out this oasis amid a rising tide of homophobia infuses these scenes with almost unbearable poignancy … Stuart quickly proves himself an extraordinarily effective thriller writer. He’s capable of pulling the strings of suspense excruciatingly tight while still sensitively exploring the confused mind of this gentle adolescent trying to make sense of his sexuality … The result is a novel that moves toward two crises simultaneously: whatever happened with James in Glasgow and whatever might happen to Mungo in the Scottish wilds. The one is a foregone calamity we can only intuit; the other an approaching horror we can only dread. But even as Stuart draws these timelines together like a pair of scissors, he creates a little space for Mungo’s future, a little mercy for this buoyant young man.”

–Ron Charles (The Washington Post)

2. Jennifer Egan, The Candy House

(Scribner)

13 Rave • 5 Positive • 3 Mixed • 2 Pan

“Many of the characters are in difficult, ethically murky lines of tech-adjacent work … It is Egan’s great gift that these stories nevertheless feel deeply human. The absurdist science-fiction elements act as a kind of backdrop for poignant affairs of the heart … Ennui, lost love, a sense of too-lateness, bitterness, jealousy—these make up The Candy House. Technology infuses the themes with new and distinct angles, but they remain fundamental to how Egan sketches her fictional world … At the heart of the novel are questions about collectivity … Some of these same questions animated A Visit from the Goon Squad too … But they become more explicit and fraught in The Candy House, which features a smattering of the same characters and those loosely connected to them … Egan remains a master of the form, that of the interlinked but not always connected stories, which provide glimpses of lives that are both brief and deep. She weaves them together in ways that are not obvious.”

–Sophie Haigney (Air Mail)

3. Emily St. John Mandel, Sea of Tranquility

(Knopf)

10 Rave • 1 Positive • 1 Mixed

“In Sea of Tranquility, Mandel offers one of her finest novels and one of her most satisfying forays into the arena of speculative fiction yet, but it is her ability to convincingly inhabit the ordinary, and her ability to project a sustaining acknowledgment of beauty, that sets the novel apart. As in Ishiguro, this is not born of some cheap, made-for-television, faux-emotional gimmick or mechanism, but of empathy and hard-won understanding, beautifully built into language … It is that aspect of Sea of Tranquility, Mandel’s finely rendered, characteristically understated descriptions of the old-growth forests her characters walk through, the domed moon colonies some of them call home, the robot-tended fields they gaze over or the whooshing airship liftoff sound they hear even in their dreams, that will, for this reader at least, linger longest.”

–Laird Hunt (The New York Times Book Review)

1. Richard Overy, Blood and Ruins

(Viking)

8 Rave • 1 Positive

“…let’s praise Overy’s stupendous achievement. Anybody interested in the why and how of boundless violence in the 20th century should make space for Blood and Ruins on his or her shelf. It will help you to grasp and revisit the carnage of 1931-45 as the largest event in human history. No continent, no ocean was spared, and Overy deftly weaves all the subplots into one planetary tapestry of merciless ideology and industrialized extermination. This book is not Eurocentric, but truly geocentric … Blood and Ruins dissects the sinews of war with the sharpest of scalpels. With myriad facts, it is not for the night stand, where it must compete with Netflix. But it is history at its best, down to the finest points culled from a dozen archives around the world … While watching the talking heads on CNN, keep this masterly work by your side.”

–Josef Joffe (The New York Times Book Review)

2. Elizabeth Alexander, The Trayvon Generation

(Grand Central)

7 Rave

“[In] Elizabeth Alexander’s beautiful, relevant book, The Trayvon Generation, the poet redefines the proximity of Black identity to loss as an opportunity to create new rituals and a new paradigm … Alexander is focused both on memory, recollecting parts of ourselves and psyches, and also on repair and replenishing through a shift in perspective, helped along by the beautiful art from a range of artists including Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson, and Kara Walker throughout. The work of Black artists in these pages elevates the conversation at the heart of the book … Like a prose poem, The Trayvon Generation is deceptively succinct even as it humanizes our needlessly dead, the incarcerated, the many survivors of instantiations of Black inferiority. The book offers wisdom, reflection, and reportage with a crystalline precision infused with a powerful, elegant empathy … This is one dazzling, beautiful aspect of The Trayvon Generation; joy as an act of resistance.”

–Joshunda Sanders (The Boston Globe)

3. Ben McGrath, Riverman

(Knopf)

4 Rave • 3 Positive • 1 Mixed

“If the missing-person element provides the current that sweeps Riverman forward, the book amounts to much more: a portrait of forgotten American byways and the eccentric characters who populate them, a cursory history of river travel in America and, not least, an effort to solve the riddle of Conant himself — not only his whereabouts but also his elusive and irresistible nature. As a chronicle of perseverance and inchoate questing, this quietly profound book belongs on the shelf next to Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild … A second book runs beneath the surface of Riverman like an undercurrent, and hints at the reasons McGrath is so drawn to Conant’s story. In an age when everything is relentlessly online and the real world is increasingly mediated through screens, Conant and his canoe represent something slower and quieter, closer to nature … McGrath sets all of this down in prose that is poised and elegant, almost circumspect … In one sense McGrath never solves the mystery that opens his book: He doesn’t recover the body. But he does something at least as impressive from a journalistic perspective: He recovers the person, and he restores him to life on the page.”

–Gregory Cowles (The New York Times Book Review)

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.