The trouble was, I had been inadequate all along, I simply hadn’t thought about it.

*

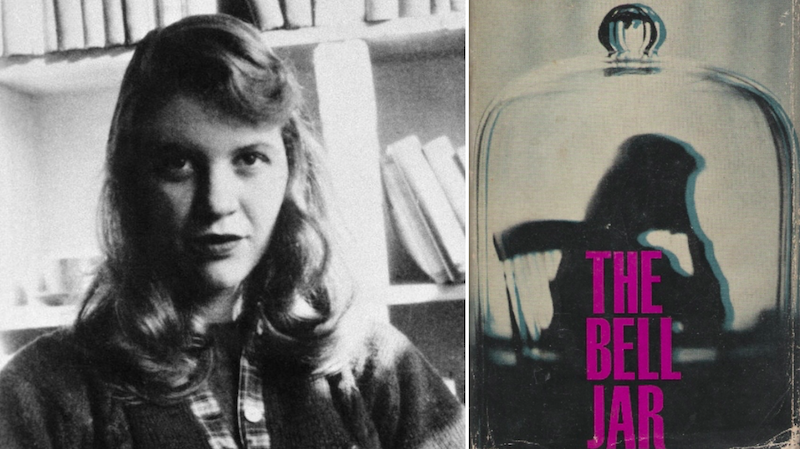

“The Bell Jar is a novel about the events of Sylvia Plath’s 20th year: about how she tried to die, and how they stuck her together with glue. It is a fine novel, as bitter and remorseless as her last poems—the kind of book Salinger’s Franny might have written about herself 10 years later, if she had spent those 10 years in Hell. It is very much a story of the fifties, but written in the early sixties, and now, after being effectively suppressed in this country for eight years, published in the seventies.

F. Scott Fitzgerald used to claim that he wrote with ‘the authority of failure,’ and he did. It was a source of power in his later work. But the authority of failure is but a pale shadow of the authority of suicide, as we feel it in Ariel and in The Bell Jar. This is not so much because Sylvia Plath, in taking her own life, gave her readers a certain ghoulish interest they could not bring to most poems and novels, though this is no doubt partly true. It is because she knew that she was ‘Lady Lazarus.’ Her works do not only come to us posthumously. They were written posthumously. Between suicides. She wrote her novel and her Ariel poems feverishly, like a person ‘stuck together with glue’ and aware that the glue was melting. Should we be grateful for such things? Can we accept the price she paid for what she has given us? Is dying really an art?

There are no easy answers for such questions, maybe no answers at all. We are all dying, of course, banker and bum alike, spending our limited allotment of days, hours and minutes at the same rate. But we don’t like to think about it. And those men and women who take the matter into their own hands, and spend all at once with prodigal disdain, seem frighteningly different from you and me. Sylvia Plath is one of those others, and to them our gratitude and our dismay are equally impertinent. When an oracle speaks it is not for us to say thanks but to attend to the message.

“…this personal life is delicately related to larger events—especially the execution of the Rosenbergs, whose impending death by electrocution is introduced in the stunning first paragraph of the book. Ironically, that same electrical power which destroys the Rosenbergs, restores Esther to life. It is shock therapy which finally lifts the bell jar and enables Esther to breathe freely once again. Passing through death she is reborn. This novel is not political or historical in any narrow sense, but in looking at the madness of the world and the world of madness it forces us to consider the great question posed by all truly realistic fiction: What is reality and how can it be confronted?

In The Bell Jar, Sylvia Plath has used superbly the most important technical device of realism–what the Russian critic Shklovsky called ‘defamiliarization.’ True realism defamiliarizes our world so that it emerges from the dust of habitual acceptance and becomes visible once again. This is quite the opposite of that comforting false realism that presents the world in terms of clichès that we are all too ready to accept.

“Esther Greenwood’s account of her year in the bell jar is as clear and readable as it is witty and disturbing. It makes for a novel such as Dorothy Parker might have written if she had not belonged to a generation infected with the relentless frivolity of the college- humor magazine. The brittle humor of that early generation is reincarnated in The Bell Jar, but raised to a more serious level because it is recognized as a resource of hysteria. Why, then, has this extraordinary work not appeared in the United States until eight years after its appearance in England?”

–Robert Scholes, The New York Times, April 11, 1971