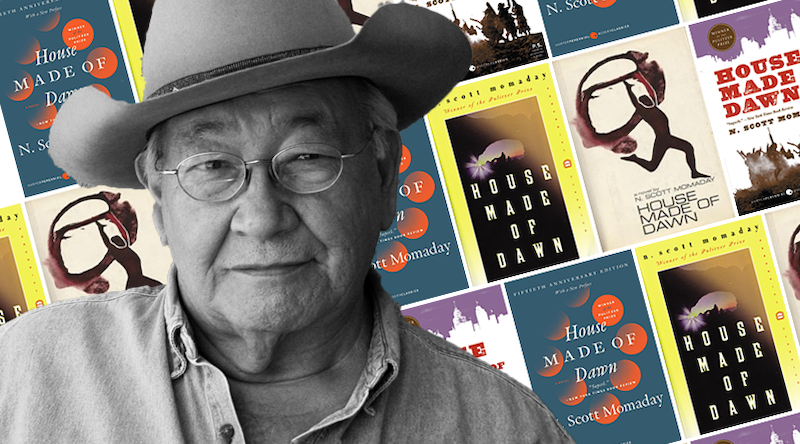

We should all be talking about N. Scott Momaday right now.

Why right now, you ask? Well, for one thing, the pioneering Kiowa writer just turned eighty-five years old. For another, Words From a Bear—a documentary examining his life, writings, and enigmatic mind—just premiered at Sundance. Perhaps most importantly though, 2019 marks fifty years since House Made of Dawn, Momaday’s spellbinding debut novel, won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. The win made Momaday the first Native American recipient of a Pulitzer, in any category, in the then-fifty-two-year history of the award, and helped launch what became known as the “Native American Renaissance”—a nationwide emergence (as well as a rediscovery and wider recognition) of Native art and literature in a wide variety of forms. (Other writers typically associated with this movement include Leslie Marmon Silko, Joy Harjo, Simon J. Ortiz, and Louise Erdrich, to list just a few.)

Momaday—a novelist, short story writer, essayist, poet, and academic—has devoted his life to preserving the Native American oral and cultural traditions, in part by educating students and the wider public about sacred places and practices. He was named a UNESCO Artist for Peace and an Oklahoma poet laureate; given the first ever Lifetime Achievement Award from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas; honored with the 2007 National Medal of Arts for “introducing millions worldwide to the essence of Native American culture”; and will, on May 1 of this year, receive the Ken Burns American Heritage Prize at a ceremony in the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

As for House Made of Dawn itself, the book began as a series of poems and eventually morphed into a lyrical novel about a young man named Abel who returns to his New Mexico reservation after fighting in WWII and tries to reconnect with the values and traditions instilled in him by his grandfather, but finds himself emotionally severed from this previous life, caught between two different worlds. It’s an incredibly powerful, moving tale, which has been widely praised for its humane characterization, intricate construction, and evocative detailing of Indian life.

Below, to mark the anniversary, we take a look back at two reviews—one classic, one contemporary—of this iconic novel.

*

And the single deep voice of the singers lay upon the dance, lay even upon the valley and the earth, whole and inscrutable, everlasting.

“This first novel, as subtly wrought as a piece of Navajo silverware, is the work of a young Kiowa Indian who teaches English and writes poetry at the University of California in Santa Barbara … It is the old story of the problem of mixing Indians and Anglos. But there is a quality of revelation here as the author presents the heartbreaking effort of his hero to live in two worlds … Young Abel comes back to San Isidro to resume the ancient ways of his beloved long-haired grandfather, Francisco. Abel is full of fears that he has relaxed his hold on these ways, after living like an Anglo in the Army. He is our tortured guide as we see his Indian world of pollen and rain, of houses made of dawn, of feasts and rituals to placate the gods, of orchards and patches of melons and grapes and squash, of beautiful colors and marvelous foods such as pike, pose, loaves of sotobalau, roasted mutton and fried bread. It is a winless ‘world of wonder and exhilarating vastness.’

…

“Abel’s troubles begin at once. He has a brief and lyrical love affair with a white woman from California seeking some sort of truth at San Isidro. Then he runs afoul of Anglo jurisprudence, which has no laws covering Pueblo ethics. He is paroled to a Los Angeles relocation center and copes for a time with that society, night Anglo nor Indian. He attends peyote sessions; he tries to emulate his Navajo roommate, who almost accepts the glaring lights and treadmill jobs, the ugliness of the city and the Anglo yearning to own a Cadillac. Abel cannot ‘almost’ cope. Because of his contempt, a sadistic cop beats him nearly to death. But he gets home in time to carry on the tradition of his dying grandfather. There is plenty of haze in the telling of this tale—but that is one reason why it rings so true. The mysteries of cultures different from our own cannot be explained a short novel, even by an artist as talented as Mr. Momaday.”

–Marshall Sprague, The New York Times, June 9, 1968

“Momaday maintains an economy of language throughout the novel, from the first chapter of only 307 words until the final, 185th page. He weaves together stories, details, and experiences from the Bahkyush, Kiowa, and Navajo traditions, with references to Roman Catholic and white American culture. Many of the novel’s characters were inspired by real or historical figures. Much of Abel’s pain comes from feeling like an outsider, what the author himself called ‘psychic dislocation’: the pain of being a Native American man in Los Angeles, far from his grandfather and from the life-giving, world-sustaining traditions of his home at Jemez Pueblo in New Mexico. Abel has survived the front lines of World War II, and, after his return to the United States, he struggles with depression and alcoholism. He spends time in prison. He attempts to heal. While others have pointed out that Momaday, with his short, terse sentences and journalistic style, echoes Ernest Hemingway, perhaps that is simply another way of comparing the unfamiliar to the already familiar, of bestowing value without questioning our values themselves. Abel’s story is radically transformed by his identity as a man of Native American heritage, and by the author’s poetic sensibility, a style that manifests as physical lyricism and that owes its success to the oral storytelling so important to Native American writers in general and to Momaday in particular, himself a member of the Kiowan Tribe.

…

“Used properly, categories in literature can illuminate a work instead of mystifying it—if we use them like filters on spotlights, layered colors and hues, combinations of light and shadow, we can examine a book from many different angles, holding various versions of it in our minds, without losing sight of the work itself. House Made of Dawn is both a masterpiece about the universal human condition and a masterpiece of Native American literature … House Made of Dawn is both a beautiful artistic object, a book everyone should read for the joy and emotion of the language it contains, and an important milestone in the publishing industry’s recognition of Native American voices. Making whole what’s been divided creates peace. That’s true for people, and it’s true for books.”

–Ben Pfeiffer, The Paris Review, November 22, 2017