Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, in which books journalists from around the US and beyond share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recent gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

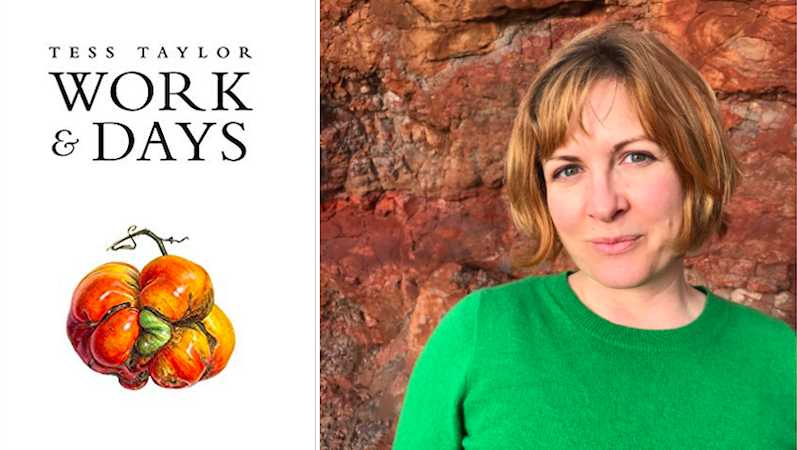

This week we spoke to poet, critic, and NBCC Poetry Chair, Tess Taylor.

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

Tess Taylor: Frankenstein. I mean, I could basically call Frankenstein one of my favorite books each year, every year. It keeps feeling relevant and hauntingly timely, but it also creates this alternate world into which you can escape. I love that the nested structure is borrowed from Ovid. I love its layering of fractured stories upon stories. I love that at its center is the figure of the monster as reader or the reader as monster. I love the figure of scientific exploration pushing us to the dangerous verge. Right now, as I answer this question, I am sitting in the eerie half light of the apocalyptic smoke storm that’s been enveloping California as a result of the fires. A glaucous sour haze. Apparently Frankenstein was conceived during a rainy and glum summer, one overshadowed by volcanic ash that was the fallout from a major eruption of a volcano in Indonesia in 1815. At the edge of Frankenstein is a volcano. At the edge of Frankenstein is environmental collapse. I’m also in awe of that, somehow.

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

TT: Oh goodness, there are so many. I believe so much that we must make and praise art amidst this devastating season, and I also see that my newscaster and editor friends are fried, harried, frazzled: it is hard to get their attention and say WE MUST DISCUSS POETRY DESPITE ALL. It’s been a tricky year that way. I was happy to get in a shout-out to Emily Wilson’s new translation of The Odyssey, which is tremendous, and to celebrate Ada Limon’s The Carrying. But there are so many more I love: Marcelo Hernandez Castillo’s haunting Cenzontle, which crosses borders real and imagined in remarkable and haunting verse; Geoffrey G. O Brien’s Experience in Groups, which uses dazzling syntax to explore possibilities for engaged political action; and Emily Jungmin Yoon’s A Cruelty Special to Our Species, a haunting revisitation of Korean comfort women and the sexual devastations of war. This was a tremendous year for poetry. I could probably go on.

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

TT: People associate critic with “critique,” and they think our job is to whinge on about things we don’t like. I rarely write about what I don’t like—I remember reading early on that Auden said the best thing to do about a poem you don’t like is to be silent about it. I’m not an endless fawning praise machine either, but I can’t write about a book unless I’m pleasantly confused by it, unless it makes my heart beat faster but I can’t yet say why. I know when I’m engrossed and perhaps even falling in love but I haven’t fully figured out why and I’m using my writing to lead me towards my explorations of that pleasure. Frost said the poem begins in delight and ends in wisdom. I guess I write criticism the same way.

I really am a hugely omnivorous reader. I honestly can never say in advance what I will like. I know I must have some tastes and act out of them—we all do!—but I really try to be a passionate and open spirit. Read, read, read. I want to be open to that pleasure, to that feeling of being caught breathlessly off guard.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

TT: A lot, and in mostly good ways. It’s so wonderful how anyone with a sense of voice and a fluency can share their thoughts through twitter. I love the public book club quality of it. And I love all the praise of books you see on Instagram: I mean, the criticism of “my current desk” or “this came in the mail” photos. It’s terrific the way that book lovers are generating excitement for books! And I love the praise culture of circulating poems that we love (“hey did you see Gabrielle Calvocoressi in the New Yorker?!”) We share instant delight. I love that. I love, for instance, how reading feels more social: Victoria Chang live tweets her readings of books, quote by quote. It’s lovely! It reminds me of reading about how, in the 18th century, as more books began to be printed, reading became a more social and less monastic activity; people would annotate their books and hand them on to others who would annotate them back. People would literally begin to fall in love with people who had annotated other books cleverly and seek to track them down. Annotation was a form of conversation and even courtship, or at least this began to be used as a plot device in 18th century novels. I mean, wow! I think that we’re having a similarly beautiful explosion of writerly and readerly sociability that is itself an extension of critical discourse.

I also love and value the social commentary that emerges over twitter about issues of race, class, gender, and inclusion. It’s wonderful to have a vivid room full of brilliant peers, fully ready to discuss aesthetics! Politics! The relation of art to life! When I was coming up, even 20 years ago, that wasn’t there and I am sort of envious of my colleagues who are 10 years younger; there’s this democratic air about it all that feels so refreshing. I love what Kaveh Akbar and Chen Chen are doing!

Nevertheless, sometimes the culture of soundbite and brouhaha and takedown is a bit overwhelming. I mean, I want readerliness to make me feel more human, not less human, and to draw me into empathy, not soundbite. To the end of cultivating the soul: I love sociability a lot but also adore solitude and have a true inner extrovert who needs feeding. I like sometimes to cultivate my private wonder. There are days when I want to turn totally inwards, and be alone, and when I read, I want to range over big, untweetable thoughts.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

TT: Oh goodness. Um…. so many! Please don’t make me pick one. I can’t. I’ll say that this year, Zadie Smith’s Feel Free, which is a book of wide-ranging cultural criticism, had a bigness of heart and of mind and spirit that made me want to be more daring as a writer, in what I do, in what I challenge myself to do. There’s this message at the core of it about intellectual pursuits being a form of freedom, a way to plot our biggest liberations. In an era that seems to want to snipe and cut away at all of us and make us feel smaller, in which it is sort of impossible not to feel smaller, I loved the way this book, in its ranginess of mind, made my mind and spirit feel bigger too. There are more books of course, a lot of them, but I think I’ll give that particular one a shout-out from my heart.

*

Tess Taylor‘s chapbook, The Misremembered World, was selected by Eavan Boland for the Poetry Society of America’s inaugural chapbook fellowship. The San Francisco Chronicle called her first book, The Forage House, “stunning” and it was a finalist for the Believer Poetry Award. Her second book, Work & Days, was called “our moment’s Georgic” by critic Stephanie Burt and was named one of the 10 best books of poetry of 2016 by The New York Times. Her work has appeared in The Atlantic,The Kenyon Review, Poetry, Tin House, The Times Literary Supplement, and other places. Taylor has received awards and fellowships from MacDowell, Headlands Center for the Arts, and The International Center for Jefferson Studies. Taylor currently chairs the poetry committee of the National Book Critics Circle and is the on-air poetry reviewer for NPR’s All Things Considered. She was a Distinguished Fulbright US Scholar at the Seamus Heaney Centre in Queen’s University in Belfast, Northern Ireland, and was most recently Anne Spencer Writer in Residence at Randolph College.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.