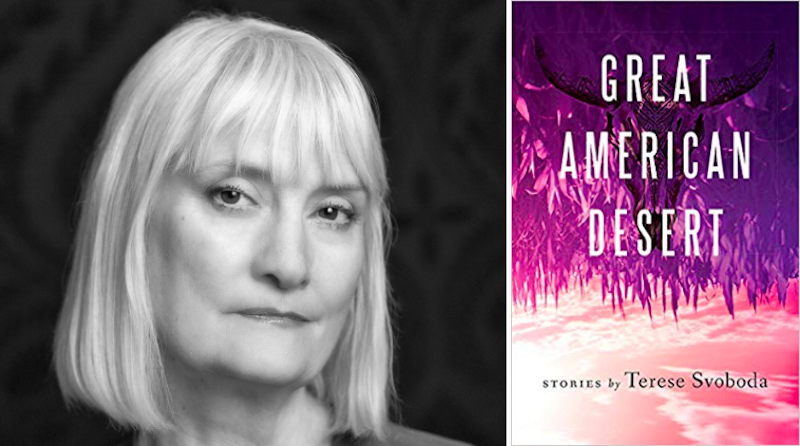

Terese Svoboda’s short story collection Great American Desert is published today. She shares five books about the Prairies with Jane Ciabattari.

But first she defines the West. “I’m from Nebraska, the state that’s smack in the middle, but I grew up on its western side, where the West begins, according to Front Street, the saloon in town that defines us. My dad was both a farmer and a rancher so I’m both Midwestern and Western. Sorting a bibliography for that, I was astounded how few books about the region exist. Sure, there’s Ladette Randolph’s A Sandhills Ballad, Tim Schaffert’s The Phantom Limbs of the Rollow Sisters, Debra Magpie Earling’s Perma Red and David Anthony Durham’s Gabriel’s Story about black cowboys, but not a lot more. Writers from there tend to write about elsewhere. I’ve done my share of that, with novels about the South Pacific and Africa, but I’ve also written Bohemian Girl and Trailer Girl, Tin God, and my memoir about my uncle, Black Glasses Like Clark Kent. These five are the books about the region that most influenced me.”

In the Heart of the Heart of the Country by William H. Gass

“This Midwest. A dissonance of parts and people, we are a consonance of Towns.” Gass’ novella in the book, “The Pederson Kid,” is a touchstone of mystery and violence, the laconic Midwestern predecessor to Brian Evenson. It was written “to entertain a toothache.”

Jane Ciabattari: It’s fascinating how Gass parallels the vast scope of the prairie with the inner lives of his characters. As a fifth-generation Kansan, descended from an abolitionist who served as a chaplain for a black regiment in the Union Army and settled in Kansas to maintain its status as a free state, I’m always aware of the battles fought and the blood shed upon these prairies. And the flatness. The storms. The snow. In the title story to this collection, Gass notes of the weather, “In the Midwest, around the lower Lakes, the sky in the winter is heavy and close, and it is a rare day, a day to remark on, when the sky lifts and allows the heart up. I am keeping count, and as I write this page, it is eleven days since I have seen the sun.” And in the same story, he writes of Billy Holsclaw, who lives alone: “…there’s simply no way of knowing how lonely and empty he is or whether he’s as vacant and barren and loveless as the rest of us are—here in the heart of the country.” How would you explain how he creates that mirroring effect of inner moods and the external landscape?

Terese Svoboda: It’s clifi, climate fiction, the genre in which climate is the character that manipulates all the others. “The Pederson Kid,” the lead novella in In the Heart of the Heart of the Country, never lets you forget the weather is freezing, not even during its wildest stream of consciousness, from the observations of the frozen boy tossed down on the pastry table “like a ham” to the hallucinations of the narrator struggling in the snow, his barely functioning counterpart. Some locales—like the prairie—are more susceptible to climate-as-character. There’s just more weather to hold sway. In the South Sudan the Nuer called themselves “the ants of God.” They live on a vast flat emptiness with an enormous sky pressing down—so like our prairie with its serious horizons. Gordon Lish, one of my teachers, piled praise on William Gass, and I found I admired Gass’ steadfast refusal to tame his vision both syntactically, and in the mirror. Ornery, like Barry Hannah, he didn’t pretty up his voice or anyone else’s.

My Ántonia by Willa Cather

Cather hovers like a raptor over Nebraska waiting to pick off aspiring writers who don’t measure up to her Park Avenue dinner-for-twenty lifestyle as a writer of national bestsellers. (Full disclosure: I wrote the afterword for the Signet Classics edition of My Antonia.) For a very long time, nobody saw irony in the immigrant woman’s story being told from the point of view of a woman impersonating a man. It’s hard without irony these days to appreciate it. Cather invented white American nostalgia, making canning a cause for celebration, rather than a nightmare of sticky boiling water.

JC: I can see what you mean by white American nostalgia. For example, Cather’s description of the prairie through her narrator Jim’s eyes—the “red of the grass made all the great prairie the color of wine-stains,” and this romantic passage:

“…light air about me told me that the world ended here: only the ground and sun and sky were left, and if one went a little farther, there would be only sun and sky, and one would float off into them, like the tawny hawks which sailed over our heads, making slow shadows on the grass.”

Why do you think My Antonia endures?

TS: Like Amy Tan’s Joy Luck Club, her book arrived at the right time to the perfect audience—in Cather’s case, when readers, bored by Henry James’s trials-of-the-rich and just a generation away from the fields, hungered to hear about the trials of the previous generation. There are still plenty of second-generation city-dwellers who would like their histories romanticized. But Cather knew it was a trap. “The trouble with you, Jim, is that you’re romantic,” says Frances in My Antonia. Cather overcame what Edmund Wilson called Ladies Home Journal writing with My Antonia’s inclusion of the suicide of Antonia’s father, a dead dog, a dead tramp, and Antonia’s toothlessness, not to mention a murder-suicide. Okay, so nobody fucks. You better not forget that the homesteaders had no choice about tearing up the virgin earth, it was plow or die. Really the book is a combination of irony, bitter sweetness, suppressed rage, and mawkishness. As a contemporary writer, I am very twisted about my response to Cather’s work but I had to face her. That’s how my novel Bohemian Girl came about.

Old Jules by Mari Sandoz

My Antonia shares the same timeframe, and is based on real people and events just as Old Jules is, but Old Jules, with recreated dialogue and scenes, and the author in third person, is billed as a biography. The first and most realistic True Grit, Sandoz tries to justify her cultured father’s cruelty as necessary to parenting on the frontier. (Full disclosure: I wrote the introduction to her Capital City reissue.)

JC: This one goes back to 1935. Sandoz describes being a girl, listening to “the accounts of the hunts, of the fights with the cattlemen and the sheepmen, of the tragic scarcity of women, when a man had to ‘marry anything that got off the train,’ of the droughts, the storms, the wind and isolation.” You’re from a much more recent generation. I’m wondering if you had similar moments of overhearing the troubles among adults in your life, and if that that inspired any of the stories in Great American Desert.

TS: I’ve had land (or “ground” as it is now known) in the region for the last twenty years, so I also had the privilege of some hearing on my own. When a thousand trucks dumped contaminated waste from the Black Hills Army Depot over the Ogallala Aquifer, I attended the presentations put on by the regional authorities (“Ogallala Aquifer” and “Bomb Jockey”). I sat next to a cowboy eating his steam table dinner, pea by pea, who smelled of burnt cowhide after branding, going on about the women descending on Winslow, Nebraska (“Endangered Species”). I watched my organic corn go blue with drought, shrivel up and disappear right back into the earth (“Dirty Thirties”). I accompanied my father as district judge when he heard the complaint about a dog set on fire (“Africa”). I withstood tornado family turmoil similar to A Thousand Acres (“Hot Rain”). I am happy to live in New York.

The Cadence of Grass by Thomas McGuane

So delightfully bitter, and better than any book I know about the modern Western family, with its wit and incisive observation executed on the grassy bits of land people in Montana fight over, as opposed to New Jersey’s. “A combine made its way while holding up homebound suburban traffic, exasperation in every direction, the guilt of the farmer evident in his slouch and his avoidance of all eye contact, his deafness to horns and abrupt passings.” No saccharine bits about the fabulous sunsets.

JC: McGuane’s Montana is indeed well-drawn. What other passages strike you as being particularly acute?

TS: With Nothing But Blue Skies, Tom McGuane was the first to capture the way my father and uncle shouted to each other about the cattle business over the phone. Yes, Maile Meloy did it too in her Half in Love but that was decades later. In The Cadence of Grass McGuane expanded that world to include concerns like “wood product debentures.” Not all Westerners are dirt farmers or sit on horses all day. He also shovelled the shit away from his reputation as a chauvinist writer. Although cowboys are the epitome of a chauvinist—just a man singing to his horse—Evelyn, the book’s female protagonist, has her own horse and a burly cross-dressing friend who helps her deal with the ex-con her father forces her to re-marry. Stand back, My Antonia.

Dust by Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor

You didn’t say what prairie, did you? A brilliant explosion of a novel, nearly science fiction to those who don’t know much about arid Kenya.

JC: Owuor’s siblings, Odidi and his sister Ajany, “were chance offspring of northern Kenya’s drylands,” Owuor writes. Growing up they had been “hemmed in by arid land geographies and essences;” they had “….painted their existence on a massive canvas of glowing, rocky, heated earth, upon which anything could and did happen.” As he is dying from a bullet wound in the streets of Nairobi, Odidi is carried back. “I want to go home.” As she carries us into this postcolonial story, which spans several decades in Kenyan history, I’m struck by the ways she shifts from life to death, creating an eerie point of view. How do you think she does that?

TS: For all the book’s pyrotechnics, it’s structured traditionally like a detective novel: dead body at the opening and the rest of the novel tells why, but that why includes the whole history of oppression and betrayal that make up the MauMau uprising and the disappointment of revolution, very Holocaust in its darkness and body count and torture. Land is being fought over, as lawlessly as the colonial cowboys in our West. More so, since Her Majesty desperately needed the majesty of Kenya (they still own vast tracts of it) to bolster her disappearing empire. Life and death shimmer on the vast horizon of Dust, one transforming the other. Sometimes Hugh Bolton, the colonial, is busy lusting after Akai, Odidi’s mother, sometimes he’s the cadaver left in the red rock cave. Petrus, the police chief, hears Odidi’s last words, holding him in a Pieta of corruption and innocence that makes sense only at the end. Ajany, the dead man’s sister, refuses to accept his death, and often addresses him as if he’s not. Indeed his pregnant girlfriend seems more adjusted to his dying than she is. Many of the other characters don’t know he’s dead and behave accordingly. Shamans can call him back to life. His coffin lies out in the hot sun unburied for a very long time in a sort of Waiting for Godot moment, with characters arriving to comment on it. I’m thinking Odidi is Kenya, about to resurrect. Owuor has a new book out this month,The Dragonfly Sea. Perhaps it’s clifi.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·