Welcome to Shhh…Secrets of the Librarians, a new series (inspired by our long-running Secrets of the Book Critics) in which bibliothecaries (yes, it’s a real word) from around the country share their inspirations, most-recommended titles, thoughts on the role of the library in contemporary society, favorite fictional librarians, and more. Each week we’ll spotlight a librarian—be they Academic, Public, School, or Special—and bring you into their wonderful world.

This week, we spoke to University at Buffalo Poetry Collection Curator, Alison Fraser.

*

Book Marks: What made you decide to become a librarian?

Alison Fraser: My first visit to the Poetry Collection at the University at Buffalo was as a visiting undergraduate researcher. I had no idea how to conduct archival research—I had never visited a special collections library before—but my thesis advisor recommended that I travel to Buffalo because the papers of the poet I was studying, Clark Coolidge, are located here. Despite my lack of experience or degrees, the Poetry Collection allowed me to request whatever I needed for my research, and I spent three happy days in Buffalo in January (which is not something you hear often!). On my last day, then-Curator Michael Basinski appeared from the stacks holding a manila envelope, sent to the Poetry Collection from Coolidge but not yet opened. He laid it on my table and announced, “Here you go, young researcher!” That was the moment I decided I wanted to become one of the curators of the Poetry Collection, which is the library of record for twentieth- and twenty-first-century poetry in English. A few years later, I returned to Buffalo to do a PhD in Poetics and worked for several years as a student assistant in the collection, and now, eleven years after my first visit, I hold a curatorial position in the Poetry Collection. I feel lucky to work with one of the largest modern poetry libraries in the world and share its holdings with students, faculty, and the public.

The excitement and thrill I had when looking through the envelope of newly arrived materials from the poet I was studying is repeated every day as I work with our print and archival materials, which include the world’s largest and most comprehensive James Joyce Collection, and major collections of Dylan Thomas, William Carlos Williams, Wyndham Lewis, Robert Duncan, and the Jargon Society, along with less well known but equally exciting collections like those of Hand and Flower Press, Jean Starr Untermeyer, and Helen Luster. Sharing our cultural heritage with students, faculty, and the community (local and international) is the most rewarding aspect of my job.

BM: What book do you find yourself recommending the most and why?

AF: I love recommending books from our Poetry Objects section because they are books you are unlikely to see anywhere else. Favorites include Tyrone Williams’s Trump L’oeil (Hostile Books, 2017), which is a crushed tissue box containing poems written in response to the 2016 presidential election; M. NorbeSe Philip’s The Book of Un with Undex (Container Press, 2018), which is made from a Rolodex transformed by materials found in Philip’s kitchen; and Karen Randall and Cole Swensen’s The Leyden Jar Project (Propolis Press, 2018), which is an acrylic box that holds twelve glass jars wrapped in copper and attached to a microprocessor: the book can only be read with the reader’s touch. Uniquely, The Leyden Jar Project comes with a wall plug-in cord and a solar panel to recharge the microprocessor. These book objects challenge the idea that the book can only be a codex, insist on new dimensions to physical books, and highlight the status of books as physical objects.

BM: Tell us something about being a librarian that most people don’t know?

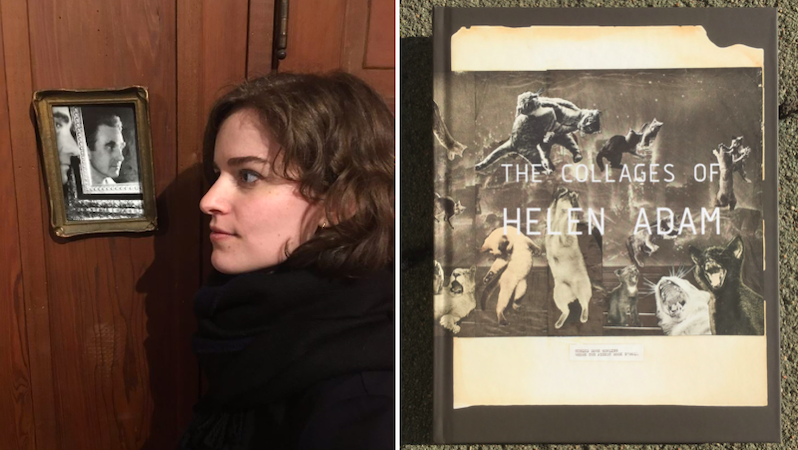

AF: Most people, even those who work in academia, don’t realize that librarians at colleges and universities can be faculty. This means that in addition to their duties within their library, they are also engaged in research. For me, research neatly dovetails with my curatorial role and my goals for the profession. My research is committed to feminist scholarship and reconsidering established narratives of the development of avant-garde poetry in the twentieth century—narratives that are often formed around the contributions of male poets. My edited book, The Collages of Helen Adam (Further Other Book Works/Cuneiform Press, 2017), is one intervention, and is based on previously unpublished materials found in the Poetry Collection, where Adam’s papers are held. This work establishes Helen Adam (1909-1993), a Scottish-American poet loosely affiliated with the Beat Generation and a member of the San Francisco Poetry Renaissance, as a visual artist and an important player in the experimental arts scene, and in so doing firmly positions her within experimental poetics in the mid-twentieth-century.

BM: What is the weirdest/most memorable question you’ve ever gotten from a library patron?

AF: Our patrons have endlessly fascinating questions about the collection, but one of my favorites came from a poet who requested occult materials in the Robert Duncan Collection. Between this collection and the collections of Helen Adam, Helen Luster, and Robert Graves (who wrote The White Goddess), the Poetry Collection holds a wealth of occult materials. This poet spent a good part of his visit with Duncan’s notebooks on the occult, and some time with Duncan’s Tarot decks. I was at the reading room reference desk when he asked if I would like him to give a reading for the Poetry Collection (the only answer is yes!). He pulled the Knight of Wands from one of Duncan’s decks, a card of energy, passion, and momentum. Later, he told me he had spoken to each of the five decks and had determined their provenance: which deck was the first Duncan had acquired, which Helen Adam had given him, which he had picked up in Paris. This poet’s engagement with the materials was a reminder that there are other dimensions outside of academic research to the archives and our work as librarians: creative inspiration, general curiosity, and affective response are as valuable as scholarship.

BM: What role does the library play in contemporary society?

AF: In a time when research libraries aim to provide the same access to digital materials, the physical, unique materials found in special collections libraries make a university’s collections distinctive. At the Poetry Collection, our mandate has always been to collect contemporary poetry, whether its future value is clear or not. Charles Abbott, who founded the Poetry Collection in the mid-1930s, explained that “We wanted to be in a position to provide [scholars] of the future with the kind of evidence that nobody had thought of saving.” It is humbling to work in the twenty-first-century world of which Abbott dreamed. At the same time, the role of the special collections library is expanding from exclusively supporting scholarly activity to integrating special collections in college classrooms and inviting the public in to experience these collections in tours, exhibits, and museums.

BM: Who is your favorite fictional librarian?

AF: I am a poetry curator, so I will respond first with some of my favorite poet-librarians: Marianne Moore, Audre Lorde, BpNichol, and Mary Barnard, who was the first curator of the Poetry Collection. But my favorite librarian is Sylvia Beach, whose library/bookshop Shakespeare and Company was a major hub for the expatriate community in Paris, and who was memorialized in Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast. The Poetry Collection’s James Joyce Collection would not be what it is without Beach, who published Joyce’s Ulysses under the imprint of Shakespeare and Company. In fact she was an archivist of her own collection, and had the prescient ability to know what materials the future scholar and Joycean would want to see—before the modern literary archives as we know them were conceived. Consequently, she saved materials that otherwise would have been trashed, such as the subscription order forms for Ulysses, which are a “who’s who” of the modernist literary world, and production materials and correspondence with the printer. She also added careful annotations to everything she received from Joyce, noting the day and occasion on which he had gifted her anything, from an early notebook of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, written in his sister Mabel’s schoolbook, to his old wristwatch band, which he discarded after Beach gave him a new one. Her memoir Shakespeare and Company is essential reading.

*

Alison Fraser, PhD, is Assistant Curator of the Poetry Collection and Interim Coordinator of the Rare & Special Books Collection at the University at Buffalo, and the editor of The Collages of Helen Adam.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·