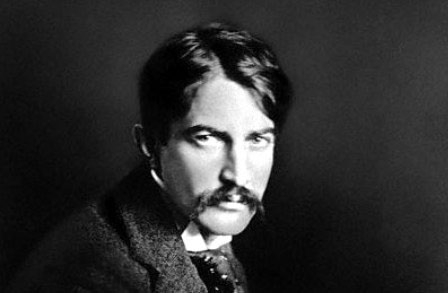

Today is the 115th anniversary of Stephen Crane’s tragic early death from tuberculosis. Jynne Dilling Martin looks back at his verse, and discovers it reads as if written yesterday. The following are selections from The Black Riders by Stephen Crane (1871-1900).

III

In the desert

I saw a creature, naked, bestial,

who, squatting upon the ground,

Held his heart in his hands,

And ate of it.

I said, “Is it good, friend?”

“It is bitter – bitter,” he answered;

“But I like it

Because it is bitter,

And because it is my heart.”

XXIV

I saw a man pursuing the horizon;

Round and round they sped.

I was disturbed at this;

I accosted the man.

“It is futile,” I said,

“You can never –”

“You lie,” he cried,

And ran on.

XLII

I walked in a desert.

And I cried,

“Ah, God, take me from this place!”

A voice said, “It is no desert.”

I cried, “Well, but –

The sand, the heat, the vacant horizon.”

A voice said, “It is no desert.”

These radically modern excerpts are taken from The Black Riders, a book-length poem by Stephen Crane, who abhorred the stuffy verse of his day. Crane preferred his own work to be called “lines” rather than “poems,” protesting to a friend that “the word ‘poet’ continually reminds me of long-hair and seems to me a most detestable form of insult.” Perhaps his insistence on not being called a poet contributed to his current neglect in the poetic canon; perhaps his larger body of fiction (Red Badge of Courage, Maggie, etcetera) outweighed this one slender volume; perhaps, even, Stephen Crane became eclipsed by his more-famous surname holder, American poetry titan Hart (no relation).

Whatever the reason, despite not being remembered as a poet, the entirety of Crane’s Black Riders is as startling and black-humored as the excerpts above, and worth reading in full. A review in The Nation called Crane “a condensed Whitman or an amplified Dickinson,” and while he may share Whitman’s penchant for conversation and Dickinson’s talent for concision and image, Crane’s originality lies in his unorthodox voice and nihilistic sensibility. Walt and Emily dwelled in belief systems of their own making, finding comfort and hope in the thought of their soul’s immortality. Crane, though, expresses the cynicism of a century he never lived to experience, when tuberculosis took his life in 1900 at a mere 28 years of age. To Crane, death is the inevitable, isolating end to a life lived in futile struggle against nature’s indifferent and overpowering forces. No special self is sung of here.

This sounds bleak, but notice how Crane honors man’s dignity even in the face of this stark knowledge: “I like it because it is bitter, and because it is my heart.” These poems are Biblical parables for a secular age: instructions for how to press through what we may feel is a lonely, barren desert of a life with clear eyes, dignity and a sense of humor.