I had only one desire: to dismember it. To see of what it was made, to discover the dearness, to find the beauty, the desirability that had escaped me, but apparently only me.

*

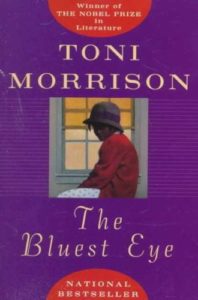

“Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye is an inquiry into the reasons why beauty gets wasted in this country. The beauty in this case is black; the wasting is done by a cultural engine that seems to have been designed specifically to murder possibilities; the ‘bluest eye’ refers to the blue eyes of the blond American myth, by which standard the black-skinned and brown-eyed always measure up as inadequate. Miss Morrison exposes the negative of the Dick-and-Jane-and-Mother-and-Father-and-Dog-and-Cat photograph that appears in our reading primers, and she does it with a prose so precise, so faithful to speech and so charged with pain and wonder that the novel becomes poetry.

“It all takes place in Lorain, Ohio, a sort of black Winesburg. We are told at the outset that Pecola Breedlove, age 11, is impregnated by her own father; Pecola will live and her child will die. ‘There is really nothing more to say,’ writes Miss Morrison, ‘except why. But since why is difficult to handle, one must take refuge in how.’ She proceeds to tell us how, and thus explains why, in a series of portraits of ‘ideal’ domestic servants, high-yellow children, preachers, drunks, whores and those abiding back women who so torment Daniel Moynihans:

Then they were old. Their bodies honed, their odor sour … They had given over the lives of their own children and tendered their grandchildren. With relief they wrapped their heads in rags, and their breasts in flannel; eased their feet into felt. They were through with lust and lactation, beyond tears and terror. They alone could walk the roads of Mississippi, the lanes of Georgia, the fields of Alabama unmolested. They were old enough to be irritable when and where they chose, tired enough to look forward to death, disinterested enough to accept the idea of pain while ignoring the presence of pain. They were, in fact and at last, free. And the lives of these old black women were synthesized in their eyes—a puree of tragedy and humor, wickedness and serenity, truth and fantasy.

“I have said ‘poetry.’ But The Bluest Eye is also history, sociology, folklore, nightmare and music. It is one thing to state that we have institutionalized waste, that children suffocate under mountains of merchandised lies. It is another thing to demonstrate that waste, to re-create those children, to live and die by it. Miss Morrison’s angry sadness overwhelms.”

–John Leonard, The New York Times, November 13, 1970

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.