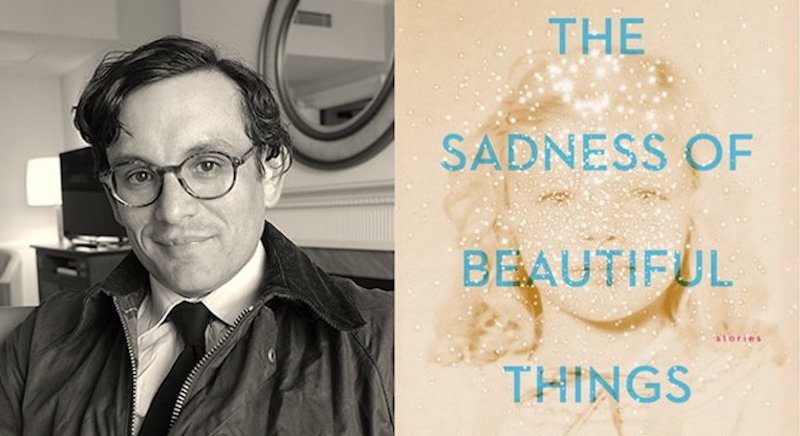

Simon Van Booy’s The Sadness of Beautiful Things is published this month. He shares five books on the sadness of love with Jane Ciabattari.

Fugitive Pieces by Anne Michaels

The first book I really connected with in terms of style and voice. Everything else on the shelf around it felt like small talk.

Jane Ciabattari: “Time is a blind guide” is an exquisite way to open a novel that mimics the way memory reacts after trauma, with flashbacks and imagined scenes. Michael’s first narrator is Jakab, a poet who at seven in Poland hides as his parents and sister are taken away by Nazis, and is rescued by a Greek archaeologist. The second narrator, Ben, is the child of Holocaust survivors who meets Jakab and becomes obsessed with tracking down his memoir. Were you most impressed with the structure, with its intersections, or the poetic language?

Simon Van Booy: Most certainly the language. For me it unearthed beauty and seriousness in everyday things and experiences. There was also deep pleasure for me in abstract sound; the words beyond their use as symbols. An unintentional music. That’s what I look (or listen) for most in books. Story is not as important for me as the feeling I have while rolling through the sentences. Reading this book also made me realize I could never, ever be bored by anything. That beneath one’s experience and immediate perception of the world, there are deep currents which are immediately accessible to those willing.

Four Quartets by T. S. Eliot

The sound and the metaphor of these poems are at the heart of why I love writing. Eliot gives the reader just enough to cast off on a long journey inward.

JC: Once again you’ve chosen literature in which time is a central pivot. Which section is your favorite?

SVB: It changes based on what is taking place in my life. That’s why I consider it a great work of art. It also mirrors the classic text by Lao Tzu in how it intentionally helps the reader unlearn certain obstructive ideas. This poem is series of keys. Each unlocks some new journey to enlightenment, by dispelling preconceived ideas rooted in place by fear, or perhaps custom.

Dubliners by James Joyce

It’s the endings of these stories I like the most, especially “The Dead” and “A Painful Case.” Emotion is carried by the sound rather than the meaning of words.

JC: I revisit “The Dead” nearly every year, and passages return to me at unexpected moments. Such a beautiful story. “A Painful Case” gives us a man whose orderliness and judgmental nature keep him mostly isolated; two years after giving up an innocent companionship with a married woman, he reads in the newspaper of her death after being hit by a train. “Now that she was gone he understood how lonely her life must have been, sitting night after night alone in that room. His life would be lonely too until he, too, died, ceased to exist, became a memory—if anyone remembered him.” Which passages strike you as most powerful in the endings of these stories?

SVB: It’s not so much the passages themselves, but the structured silence between them. They have to be read very carefully as though they are steps in a dark passage. I’m sure Joyce was aware of the hypnotic music in his work, and made decisions to increase or decrease this sensuality for the reader, depending on his instinct of what should go where and when. I certainly try to create this in my own work, which is why sometimes I choose certain unorthodox syntax which baffles copy editors. I never think of myself as telling a story, but rather enabling transformation in the characters, that can then be experienced by the reader. The story is merely a vehicle, scaffolding if you will. It’s in the nuances of sound and language—breathing controlled by punctuation where for me, the preciousness of life is cultivated. Reading not as a means to an end, but as an end in itself.

The Complete Stories of Flannery O’Connor

Original descriptions, metaphors, and syntax, along with characters brought to life with a genius Dickens would have admired.

JC: Thirty-one stories, and indeed she was a genius. I am fascinated by the way this collection circles from her first published story, “The Geranium,” written in 1946 when she was at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop (and filled with lines that dazzle, like this: “New York was swishing and jamming one minute and dirty and dead the next”) to end with “Judgment Day,” written shortly before her death at 39, and serving as a reinterpretation of the first story, with added complexity and depth. Have you ever revisited a short story, rewritten it, with new twists, as she did? (And if not, might you speculate as to why she did this?)

SVB: I often abandon stories because no matter what I do, they don’t work. It’s rather like one of those Rubik’s Cubes. You can make one small move, but the entire story has shifted on its axis and is ready to collapse. Many stories I want to tell, I simply don’t have the skill to create the experience I envision for the reader. Stories from the past were written by a different Simon. They are relics—letters with no return address. They were created by someone who doesn’t exist anymore. I have a shelf of books written by strangers with my name.

The Tao Te Ching by Lao Tzu (Stephen Mitchell translation)

Some writers unwind with a single malt, but I prefer this. It says everything there is to say with only a few words.

JC: Indeed there’s a world of wisdom in these lines. How does Lao Tzu deal with the sadness of love? Do you have a method for pulling out lines to read to unwind? I just gathered this one, for instance, in a random fashion:

When nothing is done,

nothing is left undone.

SVB: This is the perfect choice, really. The key to this work is realizing that the words themselves are simultaneously limited and limitless in their meaning. In order to go farther, the reader must make a leap of faith. But isn’t that what Voltaire suggested at the end of Candide? Genius points the way, but so often we see only the finger.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·