No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality

*

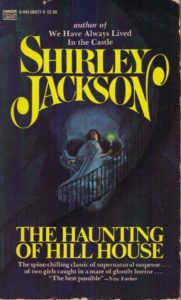

“This review of Shirley Jackson’s new novel properly begins with the confession that I am not sure of anything about it except its almost unflagging interest. The obliqueness, the tangential darlings of Miss Jackson’s uniquely imaginative mind occasionally conflict with the forward movement of her narrative, but they do not undo her spell. In The Haunting of Hill House, she has produced caviar for the connoisseurs of the cryptic, the bizarre, the eerie, guiding us along the frontiers between commonplace reality and some strange ‘absolute reality’ of her own.

“Hill House stands near Hillsdale in a region that smacks of back-country New England. The house has an evil reputation and has long been shunned. Dr. Montague, investigator of psychic phenomena, wishes to live in it for a summer with three companions: Luke, a nephew of the owner, and two young women, Eleanor and Theodora. They are strangers to each other. The invitations to the two girls had come because Eleanor as a child had been close to poltergeist phenomena (which she does not remember), and Theodora has a record of marked extrasensory perception. Neither girl fully understands her own motive for coming, except that for Eleanor it is the first prospect of adventure in a dreary life.

“Thirty-two years old, she ‘could not ever remember being truly happy in her adult life; her years with her mother had been built up devotedly around small guilts and small reproaches, constant weariness, and unending despair. Without ever wanting to become reserved and shy, she had spent so long alone, with no one to love, that it was difficult for her to talk, even casually, to another person without self-consciousness and an inability to find words . . . During the whole underside of her life, ever since her first memory, Eleanor had been waiting for something like Hill House.’

“Eleanor is the focal figure of the book. The events in which the house asserts its particular properties increasingly close upon and isolate her. She feels, with horror, that ‘it knows my name.’ Meanwhile a disquieting doubt is sown in the reader’s mind. Is Eleanor at Hill House or not? If there, how is she there? To compound the riddle, in whatever sense she is there at all, it seems certain that she stays there. If this perplexes you, it is by intent. The story must not be told here. It’s enough to say that at certain moments, quietly, in quick, subtle transitions of tone, Miss Jackson can summon up stark terror, make your blood chill and your scalp prickle.

“Who can understand Hill House? The walls are imperceptibly out of plumb, the halls are labyrinthine, the is an inexplicably cold area at its nursery door. Its enigma is unpenetrated and even what happens there is shadowy. Dr. Montague says, ‘The concept of certain houses as unclean or forbidden—perhaps sacred—is as old as the mind of man . . . Hill House, whatever the cause, has been unfit for human habitation for upwards of twenty years.’ It is ‘disturbed, perhaps. Leprous. Sick. Any of the popular euphemisms for insanity; a deranged house is a pretty conceit.’

“With her ‘conceit’ of Hill House, whether pretty be the word for it or not, Shirley Jackson proves again that she is the finest master currently partitioning in the genre of the cryptic, haunted tale. To all the classic paraphernalia of the spook story, she adds a touch of Freud to make the whole world kin.”

–Edmund Fuller, The New York Times, October 18, 1959