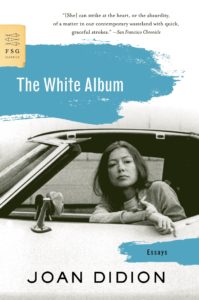

We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

*

“Joan Didion is the poet of the Great Californian Emptiness. She sings of a land where it is easier to Dial-A-Devotion than to buy a book, where the freeway sniper feels ‘real bad’ about picking off a family of five, where kids in High Kindergarten are given LSD and peyote by their parents, where young hustlers get lethally carried away while rolling elderly film-stars, where six-foot-two drag queens shop for fishnet bikinis, where a 26-year-old woman can consign her five-year-old daughter to the centre divider of Interstate 5: when her fingers were prised loose from the fence 12 hours later, the child pointed out that she had run after the car containing her family for ‘a long time.’

…

“No longer can Miss Didion regard the neurotic waywardness and vulgar infamies of California as simply ‘good material’. The White Album deals with the late Sixties and early Seventies. During these menacing years Miss Didion lived with her husband and daughter in a large house in Hollywood, at the heart of what a friend described as a ‘senseless-killing neighborhood.’ Across the street, the one-time Japanese Consulate had become a group-therapy squat for unrelated adults. Scientologists used to pop by and explain to Miss Didion about E-meters and how to become a Clear. High-minded narcotic dealers would call her on the telephone (‘what we’re talking about, basically, is applying the Zen philosophy to money and business, dig?’). Pentecostalist Brother Theobold informed her that there were bound to be more earthquakes these days, what with the end of time being just round the corner. One night a baby-sitter remarked that she saw death in Miss Didion’s aura; in response, Miss Didion slept downstairs on the sofa, with the windows open. Then it happened—not to Joan Didion, but to Jay Sebring, Abigail Folger, Boytek Frykowski, Steven Parent, Rosemary and Leno LaBianca, and Sharon Tate:

On August 9, 1969, I was sitting in the shallow end of my sister-in-law’s swimming pool in Beverly Hills when she received a telephone call from a friend who had just heard about the murders at Sharon Tate Polanski’s house on Cielo Drive. The phone rang many times during the next hour. These early reports were garbled and contradictory. One caller would say hoods, the next would say chains. There were twenty dead, no, twelve, ten, eighteen. Black masses were imagined, and bad trips blamed. I remember all of the day’s misinformation very clearly, and I also remember this, and wish I did not: I remember that no one was surprised.

And, at a stroke, the Sixties ended—‘the paranoia was fulfilled.’

…

“Miss Didion, however, has come out. She stands revealed, in The White Album, as a human being who has managed to gouge another book out of herself, rather than as a writer who gets her living done on the side, or between the lines. The result is a volatile, occasionally brilliant, distinctly female contribution to the new New Journalism, diffident and imperious by turns, intimate yet categorical, self-effacingly listless and at the same time often subtly self-serving. She can still find her own perfect pitch for long stretches, and she has an almost embarrassingly sharp ear and unblinking eye for the Californian inanity. Seemingly obedient, though, to the verdicts of her psychiatric report, Miss Didion writes about everything with the same doom-conscious yet faintly abstract intensity of interest, whether remarking on the dress sense of one of Manson’s henchwomen, or indulging her curious obsession with Californian waterworks in these pieces, Miss Didion’s writing does not ‘reflect’ her moods so much as dramatize them. ‘How she feels’ has become, for the time being, how it is.

“However much she would resist the idea, Miss Didion’s talent is primarily discursive in tendency. As is the case with Gore Vidal, the essays are far more interesting than the fiction. The novels get taken up, with the enthusiasm, the unanimity, the relief which American critics and readers often show when they discover a new and distinctly OK writer. Miss Didion is already being called ‘major,’ a judgment that some might think premature, to say the least: but she is far more rewarding than many writers similarly saluted. In particular, the candour of her femaleness is highly arresting and original. She doesn’t try for the virile virtues of robustness and infallibility; she tries to find a female way of being serious. Nevertheless, there are hollow places in even her best writing, a thinness, a sense of things missing.

“There are two main things that aren’t there. The first is a social dimension. At no point in The White Album does Miss Didion think about the sort of people she would never normally have cause to come across … Miss Didion sensed this, in Slouching towards Bethlehem, and had the energy to follow it up: but in The White Album her imaginative withdrawal seems pretty well complete. It must be easier to get like this in California than anywhere else on earth. Even the black revolutionaries Miss Didion goes to see chat about their BUPA schemes and the royalties on their memoirs. It is interesting, though, that Miss Didion fails to identify a strong element in the ‘motives’ behind the Manson killings: the revenge of the insignificant on the affluent. What frightened Miss Didion’s friends was the idea that wealth and celebrity might be considered sufficient provocation to murder. But Miss Didion never looks at things from this point of view. It is a pity. If you are rich and neurotic it is salutary in all kinds of ways to think hard about people who are poor and neurotic: i.e. people who have more to be neurotic about. If you don’t, and especially if you are a writer, then it is not merely therapy you miss out on.”

–Martin Amis, The London Review of Books, February 7, 1980