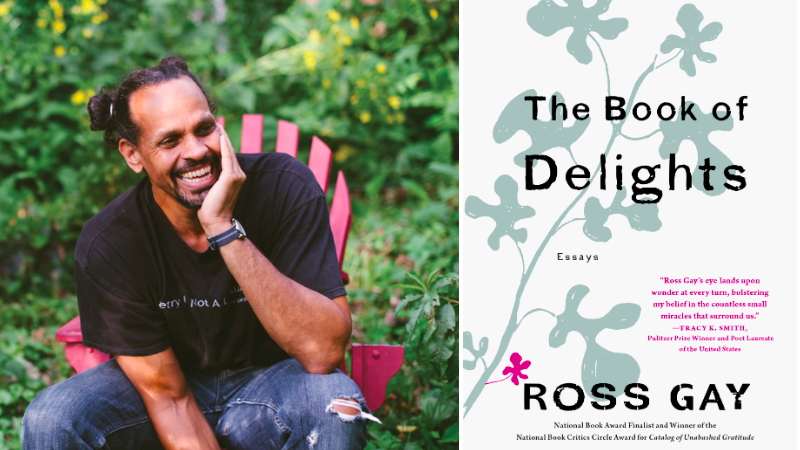

Poet Ross Gay’s essay collection, The Book of Delights, is published this month. He shares five books of delight with Jane Ciabattari.

The Black Maria by Aracelis Girmay

Such deep and true contemplation and mourning and study and dreaming about the violence and capacity for holding and care we have and might have.

Jane Ciabattari: Yes, she covers so much ground! The passage in which she defines “the black maria,” for instance:

1600s: European ships heave fatly with the weight of black grief, black

flesh, black people, across the sea; the

astronomers think the moon’s dark marks are also seas & call them

“the black maria.”

This echoes poems about Neil deGrasse Tyson, the black astrophysicist/Hayden Planetarium director. “In his youth,” Girmay notes, “deGrasse Tyson was confronted by police on more than one occasion when he was on his way to study stars.” She shows the disconnect between his intentions and a neighbor woman’s perceptions:

…His neighbor

(it is important to mention here

that she is white) calls the police

because she suspects the brown boy

of something, she does not know

what at first, then turns,

with her looking,

his telescope into a gun,

his duffel into a bag of objects

thieved from the neighbors’ houses…

How do you explain her ability to stretch from one end of the human spectrum to its opposite, within a matter of lines?

Ross Gay: I don’t know that I can explain it. And that, maybe, is part of why I love it so much, and reach for it, and point to it. There is a kind of thinking that is more than thinking happening, and it has to do with the heart and the body and this beyond. This profound listening. Girmay’s work makes me feel so deeply, it makes me see, too, the tethers between us. It is some of the most rigorous, tender work I know.

To Float in the Space Between by Terrance Hayes

I love Terrance’s poems, and I love that the rangy, reaching, playful work his poems can do somehow makes it into this book, though this book is some other thing. Drawings and memoir and lyric biography and Etheridge Knight and and and…..

JC: Indeed! An adventure of text, drawings, personal anecdotes, dreams, and musings, about the poet Etheridge Knight. And Hayes writes, “This is not a biography.” To Float in the Space Between is a finalist this year for the National Book Critics Circle award in criticism (Hayes also is a finalist for his poetry collection, American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin, which won this year’s National Book Award). You won the NBCC’s poetry award for your 2015 book, Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude.) Plus from your list of five books, Girmay was a poetry finalist, Hilton Als was a criticism finalist, Painter is an autobiography finalist this year. Has being an NBCC finalist, and winning that NBCC poetry award, changed you?

RG: I don’t know that it’s changed me, though it is really nice! Though maybe it has changed me in ways I don’t have any idea of—maybe I’m making choices in my writing that something like a certain kind of public validation that an award like this makes room for, or something like that. And probably a thousand other questions like this. Or, you know, I haven’t really finished a poem in four years or so (this isn’t lament! It’s just a fact)…maybe they’re connected? Like maybe I don’t feel the need to finish a poem, I’m saying. Oh can of worms. All of which is to say, again, I don’t know! But it’s sweet as hell, lucky as hell, to know some people were moved by the work.

Old in Art School by Nell Irvin Painter

This book is so brilliant and, like, delightful. One of our preeminent historians and intellectuals goes back to college and then grad school to study art, with college kids, and has all the confusions and pleasures and anxieties and disappointments and realizations you might expect, but don’t expect. I love this book.

JC: Painter, author of The History of White People, is an inspiration, retiring from Princeton and taking up art in a serious manner, going for a BFA and an MFA. Does she make you feel like doing similar exploring? How does her experience of making art compare to being a poet?

RG: Yes, she’s a model in this way. How beautiful to be both the expert and the beginner. I want to want to (not a typo) be a beginner at something(s) for my whole life. It’s hard work not to be good at stuff after being good at stuff. But not being good at stuff is often how you’re beautiful at stuff, seems to me. Although she’s an amazing artist, go figure.

I feel like that newness or amateurness, is really what I love about making poems, or writing the Delights, or writing this next book I’m working about my relationship with the earth. I don’t actually know how to do the thing I’m setting out to do. There’s some persistent relationship to wonder—maybe that’s the thing.

White Girls by Hilton Als

I don’t know. The first essay in that book is one of the very most beautiful things I have ever read.

JC: “Tristes Tropiques” is such a nuanced exploration of love and friendship, and self. And the language—run on sentences that swing you in surprising directions, the moment midway through when he introduces the friend he calls “Mrs. Vreeland” and the interweaving of their connection to Basquiat and to his friend SL, wow. Are there particular passages that stay with you?

RG: There are many passages that stick out—many many. But mostly I’m stuck by the way Als manages to make, in a sustained way, an essay that really does what the essay is—an attempt or try. I could not figure out how this essay was work the first time I read it—though I loved it, in fact that’s part of why I loved it. Then I realized, oh, this is really an essay. It’s an invention. The modes of thought, the movements of thought, the veering and sinking and musicing, they’re not by the book. They are the book. I will probably read that essay once a year til I die.

I: New and Collected Poems by Toi Derricotte

I can barely explain the kinds of thinking and feeling that Derricotte’s work makes possible for me, the kind of space she makes for me, space that makes plain that I am a we, we are an us.

JC: This book is coming out next month, and it’s exciting to know her explorations continue, as per this brief glimpse:

This is a record of fifty years

of victories in the reclamation

of a poet’s voice.

How has Derricotte helped you discover—and rediscover—your own voice? And has writing The Book of Delights—brief essays written over a year, about everything from your mother to four purple flowers collected during the walk from your house to your office, to Negreeting—nodding at every black person you see—shift you into a different voice?

RG: Derricotte’s work—the poems and the essays—has helped me (and, I will go ahead and say, many many many of us) figure out ways of expressing what feels inexpressible, which could be personal pain or sorrow, or could be shame. We often think of innovation in terms of technique, etc, and Derricotte has plenty of that. I think so many of our most important books, books that linger in the regions between poem/essay/memoir, that employ lineated verse and prose, etc, are made possible by Derricotte’s work, maybe beginning with Natural Birth, but extending to The Undertaker’s Daughter. Her work has made a lot of our work possible. So that’s first.

But second and equally crucial to the technical innovation is what maybe is a kind of innovation as well, which is her ability to write so honestly about shame, which I think is profoundly difficult. I mean, shame in itself resists revelation, requires concealment. But Derricotte has done this incredible service for our literature and hearts by writing very clearly about shame. Which is a kindness. And, it’s not shame exclusively! It’s this very adult relationship to the world, to life, which understands that because brutality and violence is a feature of our lives, it is not what our lives are made of. There’s also deep love, fleeting love, goldfish love, and on and on and on. Ha, the more I answer this question, the more I realize Derricotte is even more influential to me than I even thought. This is all to say, Derricotte has kind of given me my voice.

And I think writing these Delights has tuned me, frankly, to the fact that we are constantly tending to each other. Even in the midst of what’s awful, or what can seem to be primarily awful, here we are, caring for each other, doing what we are actually meant to do. Caring for each other. Your question is about a shift in voice—and the shift in voice is maybe learning that my vocation, which comes from the word for calling, which is an outside and inside voice, is studying how we care for each other. And how we might better. Which is also one of the ways of saying, my vocation has become clear: I’m studying joy.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.