He looked exactly like the statues of gods, except that his head

was slightly larger and rounder than it should be.

*

“Before this year, when the British Book Marketing Council made Mrs. Caliban controversial by naming it one of the 20 ‘greatest [American] novels since World War II,’ Rachel Ingalls’s concise, affecting and highly original 1982 work was almost unknown. Now, republished and book-clubbed, it is for the first time accessible to a wide audiece. Readers will not be disappointed.

Dorothy, the book’s eyes and ears, has not had an easy time of it. Gradually we learn that her young son has died, she has miscarried a baby, and the dog she bought as a grief-companion has been killed. Her husband, Fred, is uncommunicative and twice unfaithful in especially hurtful ways. Her best and only friend, Estelle, is neurotic, alcoholic and at odds with her adolescent children.

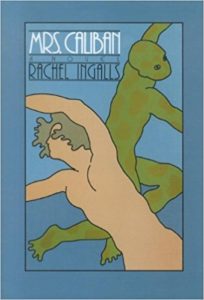

As if to balance all this sorrow, Dorothy hears private, encouraging messages on the radio and is host and lover to a 6-foot-7-inch humanlike amphibian named Larry … Larry has problems of his own: he is in hiding after righteously disemboweling the scientists who, under the guise of research, have forced him into a kinky menage a trois, and for dinner he prefers the box to the cornflakes it contains. To say that Larry finds the middle-aged Dorothy attractive is to put it mildly. ‘They made love on the living-room floor and on the dining-room sofa and sitting in the kitchen chairs, and upstairs in the bathtub.’

“The ‘Monsterman’ temporarily solves all Dorothy’s problems. ‘Now that you’ve come, everything’s all right,’ she tells him. Before, ‘she had no interests, no marriage to speak of, no children. Now at last she had something.’ She has somebody to love, and that somebody comes from the never-never land of abiding contentment, where change does not bring dissatisfaction. ‘The thing you want is the thing you have,’ he says. Dorothy seems to take this philosophy to heart. When Fred confesses his latest adultery, she thinks, ‘Well . . . I have Larry. I can afford to be forgiving.’ And since Larry is out for the evening, she sleeps with Fred. That night the amphibian, like an Oedipal son jealous of his mother’s affections, kills again and the search for him heats up. The novel concludes in surreal action in which everything, fact and fantasy, tumbles together and unravels.

“Rachel Ingalls has created a tight, intriguing portrait of a woman’s escape from unacceptable reality and presented an account of derangement so matter-of-fact, so ordinary and at the same time so bizarre, that through her words we experience new insight, ‘as though a man from Connecticut had been kidnapped to a foreign planet and then set down again in Norway or Japan; it wouldn’t be home, yet it would be recognizable.'”

–Michael Dorris, The New York Times, December 28, 1986