Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, a new feature in which books journalists from around the US share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recent gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic from a different part of the country, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

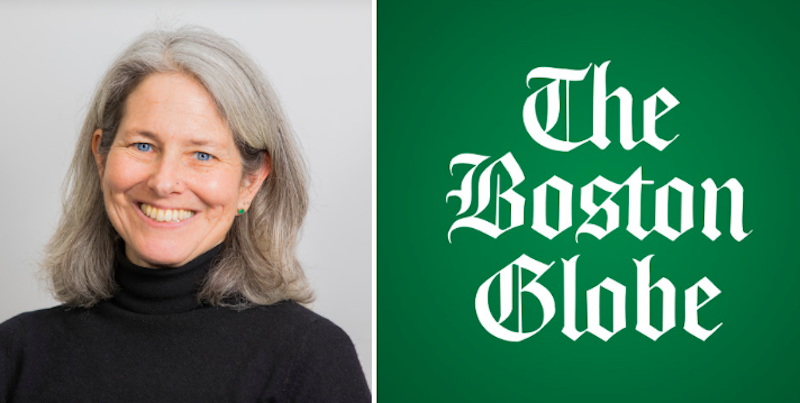

This week we spoke to writer, critic, and literacy consultant Rebecca Steinitz

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

Rebecca Setinitz: I’d have to say Bleak House, both because I love it so and because it would have been a fascinating challenge. It’s a wildly complicated book that combines social critique and detective novel, along with a plethora of romances, deaths, fortunes, misfortunes, even a case of spontaneous combustion. To do justice to that complexity without giving away too much, while also enticing readers, would have been quite the task.

As well, like all of Dickens’ novels, Bleak House was serialized, so I wonder how it would have been reviewed. As we review television shows today, assessing the first few installments, then speculating about what was to come? Or at the end, knowing that much of the audience had already read it? These are the kinds of things reviewers geek out on—at least I do.

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

RS: To my mind, the best and most important books of 2017 were by Pakistani authors. Exit West was justifiably celebrated, but I wonder if its success overshadowed two other spectacular books that were well-reviewed, but seem to have received less public attention.

Kamila Shamsie’s Home Fire resituates Antigone among Pakistani immigrants in London, following the families of a cabinet member and a jihadi as their lives entwine in Massachusetts, London, Syria, and Karachi. As someone who reads a lot, I often know where plots are going and how books are going to end, but Home Fire had me riveted until the very last paragraph, which is both shocking and inevitable.

In The Golden Legend, by Nadeem Aslam, two secular Muslim architects, a married couple, live in a poor Christian neighborhood next to an increasingly fundamentalist mosque. As religious and political tensions rise, among inhabitants of the neighborhood but also extending out to the Pakistani and US governments, the novel’s characters face terrible violence and loss, but also find powerful connections.

These urgently relevant, fiercely intelligent, beautifully written books bring Pakistan’s deep literary heritage to bear on political, religious, and humanitarian crises that have been decades in the making, standing as models for U.S. writers—and readers—as we tackle our own crises.

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

RS: Book critics themselves have two ironically antithetical misconceptions that are apparent in, on the one hand, reviews that simply summarize the book and announce that it is good—or bad—and, on the other, reviews that hardly address the book at all but instead opine on the book’s topic. Great reviewing strikes a series of balances: between description and evaluation; revealing enough about the book that readers know what they are getting into, and giving away so much that they lose interest in reading it for themselves; respecting what the book is trying to accomplish and questioning whether it succeeds.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

RS: Two standard answers are that technology and social media have crushed the newspaper book review, which used to be a mainstay of the book industry, and that Amazon, Goodreads, et al, have turned everyone into a critic, devaluing the entire enterprise. The first claim is obviously true: my editor at the Boston Globe, Paul Makishima, does a fantastic job, but over the ten years I’ve been writing for the Sunday books section, the Globe has eliminated its daily reviews and is down to only three reviews on Sunday.

At the same time, social media has made the book world more accessible, vibrant, and immediate. Personally speaking, Facebook and Twitter spread my reviews far wider than print papers on Boston-area breakfast tables, I get immediate responses from excited readers and even authors themselves, and my work feels like it’s part of a larger conversation.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

RS: I’ll read anything by Columbia English professor, voracious reader, and erudite writer Jenny Davidson: her books (especially Reading Style: A Life in Sentences, Reading Jane Austen, and her second novel, The Explosionist); her reviews for Bookforum; her blog, Light Reading; even her Facebook posts, which are small gems, whether she’s bringing her friends along as she rereads Edward Gibbon or recommending her latest crime and fantasy discoveries.

*

Rebecca Steinitz is a regular reviewer for the Sunday Boston Globe, and writes and reviews for various other publications. For several years, she wrote a monthly column about books, reading, and families at Literary Mama. Her book Time, Space, and Gender in the Nineteenth-Century British Diary is a relic of her former day job as an English professor. In her current day job as a literacy consultant, she expands the literary horizons of urban high schools.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.