The sea of grief has no shores, no bottom; no one can sound its depths.

*

“Since the publication of his first book almost four decades ago, Primo Levi has risen from obscurity to the position of a major figure in contemporary Italian letters. This rise has been without fanfare or self-advertisement: an unassuming man, Mr. Levi strikes no poses; his eminence has arrived as an ever wider public discovered his integrity, his dignity, his humanity, and his exacting literary standards.

…

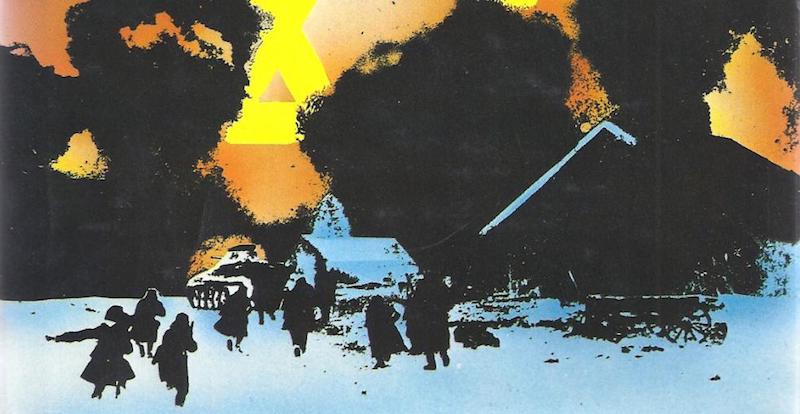

”If Not Now, When? is the fictional narrative of a Jewish partisan band’s long trek from Russia to Italy in the years 1943 to 1945 … Here Mr. Levi is writing not of his own branch of Judaism, but of Ashkenazim, of Eastern European Yiddish-speaking Jews, of whom, in common with most Italians, he knew virtually nothing until he met them in Auschwitz as fellow inmates. Pulling together material from a variety of authentic records, he tells a tale of heroism and good humor, of desperation and sympathy, in conditions of the bleakest hardship – a tale of the first Jews to organize themselves for combat ‘since Titus destroyed the Temple . . . a wretched aristocracy, the strongest, the smartest, the luckiest,” the fugitives from Nazi roundups, who by twos and threes coalesce ”along roads covered with blood.’ They include women as well as men, innocents scarcely out of boyhood, a scattering of the elderly, bone-weary with suffering, and even one Russian Christian. What holds them together is a half-mocking mutual loyalty and a burning resolve to fight their way to Palestine.

As they stubbornly push west, they manage to survive in woods and marshes and once quite literally underground; they link up with other partisans, first Russian, then Polish, and with a beleaguered little ‘republic’ of fellow Jews. Each episode, each sojourn, sometimes extended, sometimes transitory, stands in contrast with its predecessor, thus keeping the account in motion; even in rambling conversational pauses, the tension never slackens. Nor does the author resort to horrifying images of battle: when fighting occurs, he etches its outlines with a minimum of quick strokes. ‘This story is not being told,’ he informs us, ‘in order to describe massacres.’ It was a similar restraint that distinguished his chronicle of life in Auschwitz from the run of concentration camp literature.

“Despite the virtuosity with which he manipulates his literary devices, Mr. Levi’s new book lacks the intimacy, the sureness of touch so evident in his volumes of reminiscence. As he readily concedes, he has only a marginal familiarity with the life and language of the Ashkenazim. To be sure, during his protracted return from concentration camp, narrated in his Truce (1963), he traversed the terrain described here, and talked as best he could with a variety of its inhabitants. But the full force of his characters’ Yiddish still escapes him, and this linguistic difficulty is compounded by the further obstacle of translation into English. For all the talent of William Weaver, who can be relied on to give a nuanced and impeccable rendering of Italian prose, the story reaches the English-language reader through a double filter.

While in a literary sense the problem of distance may be insoluble, on the level of human values it is not. Mr. Levi turns his handicap to advantage by giving his novel a comparative twist. Lost in wonder at ‘the moonstruck world of Ashkenazic Judaism,’ he echoes his own bewilderment in that of his characters. In Italy they discover philo-Semitism, marvelous, incredible, unknown in their homelands; they learn of Christians who have befriended Jews ‘not in spite of the fact’ of their Judaism, ‘but because of it.’ In bringing together the contrasting poles of European Jewry, Mr. Levi’s story takes on the sweeping, epic quality which marked the best of his earlier work.

“And with that, Mr. Levi strikes the note we have learned to recognize in all his writing—the note of universal human sympathy. Never minimizing the pervasive anti-Semitism of the Russians and the Poles, he prefers to dwell on scattered examples of solidarity with the ragged band of Jewish survivors. For Irving Howe, whose sympathetic introduction gives Mr. Levi his full due, the doomed ‘republic of the marshes’ best represents such a moment. For me, it is Gedaleh’s encounter with the Polish Home Army officer Edek. The Pole despairs; his comrades have been crushed in the Warsaw uprising; his country’s ‘liberation’ by the Red Army looks more and more like conquest. Condemned to a futile last stand on his own soil, he envies the Jews, who ‘have a destination and a hope. . . . Maybe (the Messiah) will come for you, but for the Poles he came in vain.’ A Russian captain, this time in conversation with Mendel, echoes the envy: ‘Your choice wasn’t imposed on you. . . . You invented your destiny.’ The reiterated expression of respect shows Mr. Levi at his most persuasive: his Jews can wrest admiration and fellow feeling even from the offspring of their persecutors.”

–H. Stuart Hughes, The New York Times, April 21, 1985