There are few things the literary community relishes more than the appearance of a polarizing high-profile book. Sure, any author about to release their baby into the wild will be hoping for unqualified praise from all corners, but what the lovers of literary criticism and book twitter aficionados amongst us are generally more interested in is seeing a title (intelligently) savaged and exalted in equal measure. It’s just more fun, dammit, and, ahem, furthermore, it tends to generate a more wide-ranging and interesting discussion around the title in question. With that in mind, welcome to a new series we’re calling Point/Counterpoint, in which we pit two wildly different reviews of the same book—one positive, one negative—against one another and let you decide which makes the stronger case.

Margaret Atwood is prolific. She has published more than forty (!) books of poetry, fiction, and critical essays. In 2000, she was awarded the Booker Prize for her novel, The Blind Assassin. In 2017, she was given the PEN Lifetime Achievement Award. She is best known for her dystopian novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, published in 1985 and adapted into a hit television series just two years ago. The Handmaid’s Tale takes place in the Republic of Gilead, under a totalitarian regime that enslaves the few remaining fertile women, forbids them from reading and writing, and forces them to bear children to the barren upper class.

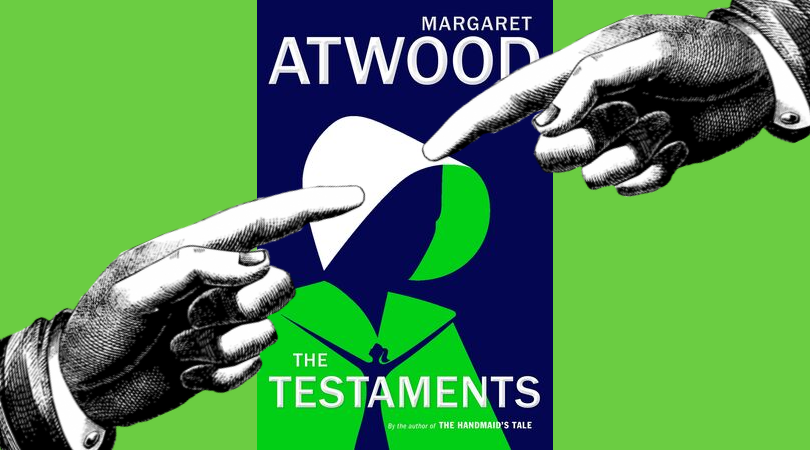

The Testaments is the much-anticipated sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale. It picks up the story more than fifteen years after the events of the original, with testaments of three female narrators from Gilead. (But you probably knew all of this, on account of being someone who clicked on this site and also maybe because of the Amazon drama and the Booker Prize drama surrounding the new title.)

Overall, The Testaments has been met with positive reviews. Vox‘s Constance Grady calls it “a hopeful book. It’s escapist. It’s a thriller. It’s a bit of a joyride.” The Guardian‘s Alex Clark refers to it as “a rallying cry for activism that argues for the connectedness of societies and their peoples.” Ron Charles wrote in The Washington Post, “Atwood responds to the challenge of that familiarity [with Gilead] by giving us the narrator we least expect: Aunt Lydia. It’s a brilliant strategic move.” Still, some reviewers felt it didn’t hold up in comparison to the original. Julie Myerson wrote in The Observer that she found it “a touch disappointing.” Laura Freeman of BBC called it “a weaker and less satisfying book.”

Today we’re focusing on Michiko Kakutani’s review, which praises the sequel as being “contrived in a Dickensian sort of way with coincidences that reverberate with philosophical significance.” In the other corner, we’ve got Rebecca Abrams’ writing in The Financial Times that The Testaments feels like “a novel pursued by its TV progeny, rushing to tie up the loose plot ends and have the final word.”

So, reader, what do you think? Are you ready to return to Gilead?

*

Only dead people are allowed to have statues, but I have been given one while still alive. Already I am petrified.

“[A] compelling sequel … It’s a contrived and heavily stage-managed premise—but contrived in a Dickensian sort of way with coincidences that reverberate with philosophical significance … Atwood’s sheer assurance as a storyteller makes for a fast, immersive narrative that’s as propulsive as it is melodramatic … Atwood wisely focuses less on the viciousness of the Gilead regime (though there is one harrowing and effective sequence about its use of emotional manipulation to win over early converts to its cause), and more on how temperament and past experiences shape individual characters’ very different responses to these dire circumstances … Atwood understands that the fascist crimes of Gilead speak for themselves—they do not need to be italicized, just as their relevance to our own times does not need to be put in boldface … it’s worth remembering that the very ordinariness of Atwood’s Offred gave readers an immediate understanding of how Gilead’s totalitarian rule affected regular people’s lives. The same holds true of Agnes’s account in The Testaments, which is less an exposé of the hellscape that is Gilead than a young girl’s chronicle … Atwood seems to be suggesting, do not require a heroine with the visionary gifts of Joan of Arc, or the ninja skills of a Katniss Everdeen or Lisbeth Salander—there are other ways of defying tyranny, participating in the resistance or helping ensure the truth of the historical record.”

–Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times Book Review

“Following up on a book like this was never going to be easy and The Testaments has a hard time of it … While The Testaments will answer some of the many questions readers have put to Atwood over the years, it barely qualifies as a dystopia, and as a work of fiction it falls far short of Atwood’s best books. The hypnotic intensity of the prose in The Handmaid’s Tale is sadly absent here, as is the playful inventiveness of recent Atwood novels such as Penelopiad or Hagseed, or the wily depths of earlier ones such as Alias Grace or The Blind Assassin. Many of the plot twists in The Testaments seem predictable and contrived … Too often The Testaments reads like a novel pursued by its TV progeny, rushing to tie up the loose plot ends and have the final word … Now is a good, even urgent, moment to be thinking about dystopias, but The Testaments offers frustratingly little to extend our knowledge or deepen our understanding. Unlike The Handmaid’s Tale, or perhaps because of it, the ground it treads is already well-worn. By inhabiting much the same territory as its predecessor, the sequel ends up feeling curiously dated. Being told in retrospect, it neuters its own menace.”

–Rebecca Abrams, The Financial Times

Deep Dive:

A classic review from 1986 of The Handmaid’s Tale

Margaret Atwood on how she came to write her dystopian novel