There are few things the literary community relishes more than the appearance of a polarizing high-profile book. Sure, any author about to release their baby into the wild will be hoping for unqualified praise from all corners, but what the lovers of literary criticism and book twitter aficionados amongst us are generally more interested in is seeing a title (intelligently) savaged and exalted in equal measure. It’s just more fun, dammit, and, ahem, furthermore, it tends to generate a more wide-ranging and interesting discussion around the title in question. With that in mind, welcome to a new series we’re calling Point/Counterpoint, in which we pit two wildly different reviews of the same book—one positive, one negative—against one another and let you decide which makes the stronger case.

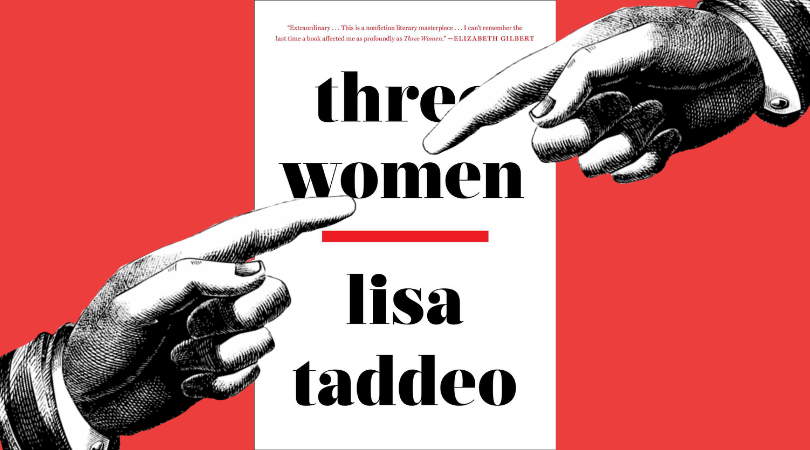

When writer and immersion journalist Lisa Taddeo began research, nearly a decade ago, for what would become Three Women, her aim was to capture the nature of desire in contemporary America. Many of her first interview subjects were actually men, but as she delved deeper into this project, she found that the more interesting and intimate portraits of desire came from the women she spoke to. (Surprise, surprise.) Taddeo spent eight years with three women in particular (Lina in suburban Indiana, Maggie in North Dakota, and Sloane in the Northeast), driving back and forth across the country six times to talk to each about their marriages, their personal traumas, and their deepest desires.

So what do the critics think of this achingly intimate book? Megan Nolan of The New Statesman loved it, writing in her review, “To spend years on these ordinary stories, as Taddeo has done, is an act of generosity and faith. It’s what storytelling is for, why we need it.” Similarly, Laura Miller of Slate praised the women’s stories as “magnificently depicted,” stating that “none of the narratives in Three Women are inspirational or empowering, but they are what the best long-form journalism should be, which is truthful.” On the more negative side, Nora Caplan-Brooker observes in her Baffler review that “despite the sensitivity Taddeo shows her subjects, this book hits a sour note when it attempts to make meaning from their lives.” The New York Times‘ Parul Sehgal couldn’t get past the writing, arguing that “[Taddeo’s] intentions partly feel wobbly because the language of the book is so inconsistent, full of odd homilies—an assembly line of truly terrible metaphors.”

Today we’re pitting Christina Patterson’s Times (UK) review against Lauren Oyler’s New Yorker analysis. The former heralds Three Women as a book that “glitters and cuts to the heart of who we are,” while the latter finds that “Taddeo’s view of women as both impossibly complicated and fundamentally constrained leads her to ascribe nonsense and clichés to them.”

After all this, reader, are you willing to spend some time with Taddeo and these three women?

*

One inheritance of living under the male gaze for centuries is that heterosexual women often look at other women the way a man would.

“[An] extraordinary book … In weaving these stories together, Taddeo paints an electrifying picture of female desire, and of the pain men casually inflict in their pursuit of sexual pleasure. She writes in searing prose that seems to capture every nuance. She doesn’t pull her punches. She calls a spade a spade and sexual intercourse a “f***” … there’s also a singing simplicity to the prose that at times lifts it to something more like poetry. At times there are biblical resonances to the prose. This seems entirely appropriate in work that is intended to capture the primal, scorching, life-changing power of sexual desire amid the banality of our daily lives. It doesn’t just aim. It succeeds. Three Women is an astonishing act of imaginative empathy and a gift to women around the world who feel their desires are ignored and their voices aren’t heard. This is a book that blazes, glitters and cuts to the heart of who we are. I’m not sure that a book can do much more.”

–Christina Patterson, The Times (UK)

“Three Women is a book for people who enjoy embarrassment by proxy, which Taddeo uses to emphasize just how ‘relatable’ these stories are … Taddeo’s view of women as both impossibly complicated and fundamentally constrained leads her to ascribe nonsense and clichés to them … Taddeo’s use of the close third person camouflages the source of these infelicities even as she seeks to expose the source of the women’s problems. The result is moral ambiguity at the level of the book’s form rather than its content … She seems to forget that a book, regardless of its mode, is not the same as a personal story or something shared over a kitchen table … By eliding the difference between the two, Taddeo replicates the conditions she purports to lament: she offers these women up to be judged … Although she asserts in her epilogue that ‘women have agency,’ she tends to patronize her subjects.”

–Lauren Oyler, The New Yorker