There are few things the literary community relishes more than the appearance of a polarizing high-profile book. Sure, any author about to release their baby into the wild will be hoping for unqualified praise from all corners, but what the lovers of literary criticism and book twitter aficionados amongst us are generally more interested in is seeing a title (intelligently) savaged and exalted in equal measure. It’s just more fun, dammit, and, ahem, furthermore, it tends to generate a more wide-ranging and interesting discussion around the title in question. With that in mind, welcome to a new series we’re calling Point/Counterpoint, in which we pit two wildly different reviews of the same book—one positive, one negative—against one another and let you decide which makes the stronger case.

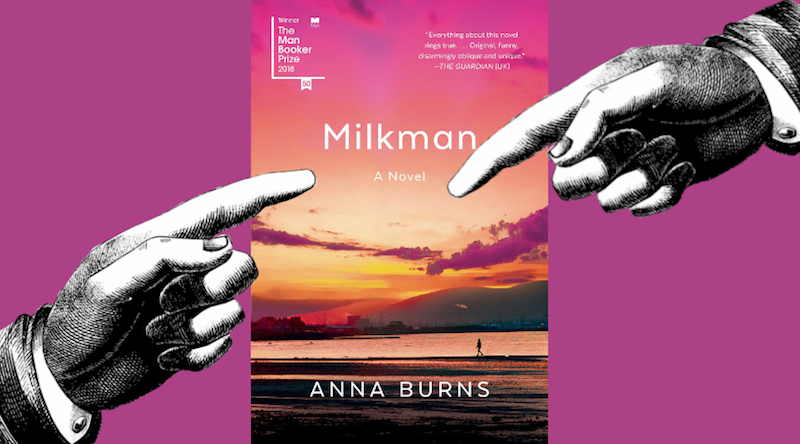

This week, we’re turning our attention to Milkman, Belfast writer Anna Burns’ 2018 Booker Prize-winning experimental novel, which was published in the US earlier this month by Graywolf Press. Set in an unspecified city in Northern Ireland in the 1970s, Milkman follows an 18-year-old girl known only as “middle sister,” who is being stalked and harassed by a sinister paramilitary figure. Pervaded by an air of menace and shot through with dark humor, the novel, in which no place or character gets a name, examines the social and gender politics of a community torn apart and traumatized by sectarian strife.

Since its Booker win in October, Burns’ novel has been rapturously received in outlets like The Guardian and The Washington Post (among, it must be said, many others), but also criticized as being “willfully inelegant” and “unrewarding” by The London Times and Vulture, which therefore qualifies it for inclusion in this series.

Now, to this installment’s combatants: Dwight Garner of The New York Times, who found the book to be “interminable,” and Mark O’Connell of Slate, who deemed it “strange and variegated and brilliant.”

*

The day Somebody McSomebody put a gun to my breast and called me a cat and threatened to shoot me

was the same day the milkman died

“Burns expands this material into a willfully demanding and opaque stream-of-consciousness novel, one that circles and circles its subject matter, like a dog about to sit, while rarely seizing upon any sort of clarity or emotional resonance. I found Milkman to be interminable, and would not recommend it to anyone I liked … the repetitions, the piling up of extraneous detail, the dashes within dashes, the sense she instills in her readers of craving verbs the way an animal craves salt … The best thing in Milkman is Burns’s occasionally sensitive portrait of this young woman’s flickering consciousness … Sometimes her pile-on sentences achieve a prickly, shambolic sort of grace … Burns has a tic as a writer, one that, once you notice it, will begin to drive you mad. She likes groupings of three, that magic number, whether she is dealing out nouns or verbs or adverbs: ‘illuminating, transcendent, contemplative;’ ‘neglect and disadvantage and disfavor;’ ‘those shudders, those tingles, the horrible sensations.’ These troikas are endless. Mostly these extra words are unnecessary, redundant and not needed. The cultural convention known as the novel can take a lot of pulling and contorting. So can readers. But Milkman requires so much effort for so modest a result.

–Dwight Garner (The New York Times)

“This might sound like a perverse strategy of willful obscurantism, but in fact Milkman’s formal strangeness proceeds naturally from the strangeness of the story it tells and the place in which it is set. In Northern Ireland during the worst years of the Troubles, proper nouns were like suspect devices: charged with violent potential, and to be treated with extreme caution … For all the simplicity of its setup, Milkman is a richly complex portrayal of a besieged community and its traumatized citizens, of lives lived within many concentric circles of oppression … Among Burns’ singular strengths as a writer is her ability to address the topics of trauma and tyranny with a playfulness that somehow never diminishes the sense of her absolute seriousness … Like Flann O’Brien and Samuel Beckett, two writers with whom she has more than Irishness in common, Burns understands the rich comic potential of trying the reader’s patience, and of lists and enumerations as a means of illuminating the absurdity of logical rigor, of language itself … The book’s long sentences, its penchant for the exhaustive, can at times be challenging, and there were stretches where I found its uncanny energies stagnated for too long. But it also seems clear to me that these insistent strategies are in service of the book’s mood of total claustrophobia, and that they contribute to, rather than diminish, its overall effectiveness … There is a pulsating menace at the heart of the book, of which the title character is an uncannily indeterminate avatar, but also a deep sadness at the human cost of conflict … For all the darkness of the world it illuminates, Milkman is as strange and variegated and brilliant as a northern sunset. You just have to turn your face toward it, and give it your full attention.”

–Mark O’Connell (Slate)