To all the devils, lusts, passions, greeds, envys, loves, hates, strange desires, enemies ghostly and real, the army of memories, with which I do battle—may they never give me peace.

-Patricia Highsmith, diary entry, 1947

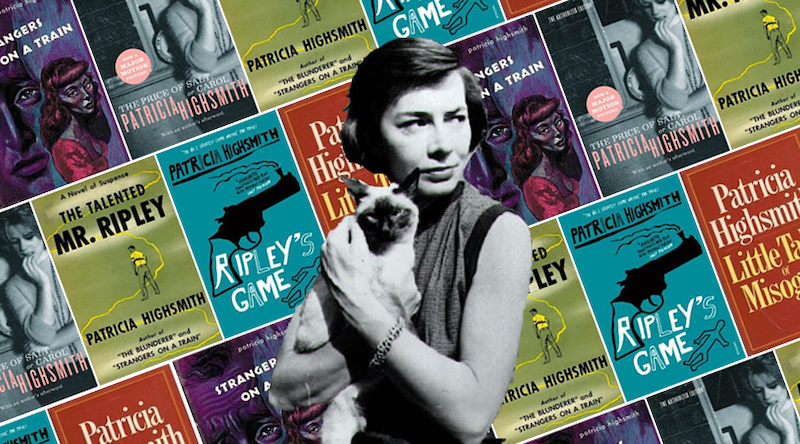

Patricia Highsmith wore many hats over the course of her life and five decade writing career. In many respects, she was a deeply contradictory figure: a master practitioner of the bleak psychological thriller who also penned the first, and for several years only, major lesbian novel with a happy ending; a self-described liberal and social democrat who seemed to have no qualms about making racist and antisemitic statements; someone who hated being around people, yet enjoyed countless affairs and short-lived romances.

Though Highsmith’s literary immortality largely rests on her creation of Tom Ripley—the suave, cold-blooded, and utterly amoral protagonist of The Talented Mr. Ripley and its four sequels—both Strangers on a Train and Carol are also rightly considered classics. Notably, the reputations of the “Ripliad,” Strangers, and Carol have all benefited from their acclaimed (and Oscar-nominated) film adaptations.

As today would have been Highsmith’s one-hundredth birthday, we thought we’d mark the occasion by excavating a selection of reviews, both classic and contemporary, of her most famous novels, as well as her deliciously-titled 1975 short story collection, Little Tales of Misogyny.

*

Strangers on a Train (1950)

The night was a time for bestial affinities, for drawing closer to oneself.

“The sphere of suspense for the story of a strange, parasitic attachment and the unbelievable events which follow. Guy Haines, on the way to Texas to divorce his wife Miriam so that he can marry Anne, is picked up by Charles Bruno, an alcoholic and a maniac, who suggests to him that he murder Miriam in exchange for Guy’s murder of the father he hates. Dismissing this at the time, Guy later finds that Miriam has been murdered, and he is haunted by the reappearance of Bruno, threats, letters. Guy, composed and reputable at the time, is finally worn down by guilt, fear, sleeplessness, and he commits the murder that Bruno lays out for him. Never free of his conscience—or of Bruno—Bruno’s accidental death is the impetus for Guy’s eventual confession….All of this seems quite unreasonable.”

–Kirkus Reviews, March 15, 1950

“…before Hitchcock’s movie came Patricia Highsmith’s 1950 novel. Highsmith’s original Strangers on a Train is a moody and disturbing excavation of guilty paranoia that bears little resemblance to the film beyond its initial premise.

…

“Highsmith perverts the workings of sympathy in her suspense stories. Sympathy means imagining oneself in another’s place, but Highsmith makes it difficult for the reader to sympathize with the characters, or for the characters to sympathize with each other. Bruno feels connected to one person only by murdering another, and Guy’s descent offers no relief for a reader looking for someone to root for.

…

“The shared decline of Bruno and Guy is less a morality play than an ugly spectacle of disintegration. ‘I find the public passion for justice quite boring and artificial,’ Highsmith wrote, ‘for neither life nor nature cares whether justice is ever done or not.’ Instead of illustrating a moral, Strangers on a Train throbs with a pervasive and inexorable tension, a gnawing pressure that erodes the characters from the inside.

That tension is Highsmith’s creative signature. Strangers was her debut novel, but her sense of anxious foreboding was already fully formed in the crucible of Cold War paranoia that surrounded her. For Highsmith, who was gay, that paranoia was shot through with anxiety, for American Cold War politics intertwined with an intense homophobia that branded homosexuals as an official national security risk. Highsmith’s creative goal, she wrote in her notebook at the time, was ‘Consciousness alone, consciousness in my particular era, 1950.’

She expressed that consciousness through guilt, but of an unusual sort. Beginning with the character of Guy in Strangers on a Train and continuing through 18 novels and scores of short stories, Highsmith’s inverted version of guilt creates the crime, not the other way around.”

–Leonard Cassuto, The Wall Street Journal, November 22, 2008

*

The Price of Salt, or Carol (1952)

It would be Carol, in a thousand cities, a thousand houses, in foreign lands where they would go together, in heaven and in hell.

“The heroine of this tale of lesbian love is a lonely 19-year-old, who has been brought up, more or less as an orphan in a semi-religious “home.” At the novel’s opening, Therese Belivet has been working for two years in New York , trying to save $1,500 for membership in the stage designer’s union. Her attempts at an affair with the young man who wants to marry her have been a failure; and she knows that she does not really love him. When she meets Carol Aird—a beautiful, wealthy, sophisticated woman of 30, who is in the process of divorcing her husband—Therese falls totally in love at first sight.

Radiantly happy in Carol’s company, Therese cannot conceive of there being anything questionable about this new relationship. When the two women take a motor trip to the West, it is Therese who, with pure blind innocence, causes them to become loves. And she thereby precipitates a crisis in which they both have to make decisions that will lastingly affect their lives.

Obviously, in dealing with a theme of this sort, the novelist must handle his explosive material with care. It should be said at once that Miss Morgan writes throughout with sincerity and good taste. But the dramatic possibilities of her theme are never forcefully developed. While Therese’s rapturous love sometimes gives a glow to the story, the novel as a whole—in spite of its high voltage subject—is of decidedly low voltage: a somewhat disjointed accumulation of incident, too much of which is pretty unexciting as story-telling and does little to deepen insight into the characters. Therese herself remains a tenuous characterization , and the other personages are not much more than silhouettes. This reader’s interest was always on the verge of being awakened—and never quite was.”

–Charles J. Rolo, The New York Times, May 18, 1952

“Highsmith published the novel in 1952, under the pseudonym Claire Morgan. She was understandably wary of derailing her career, but she also may have been uncomfortable with the book’s exaltation of love. Highsmith never wrote another book like it; indeed, her work became known for its ostentatious misanthropy. And for the next four decades she publicly dodged any connection to a book of which she had every right to be proud.

Highsmith was a pared-down, precise writer whose stories rarely strayed from the solipsistic minds of her protagonists—most of them killers (like the suave psychopath Tom Ripley) or would-be killers (like the unhappy husbands in several of her books). The Price of Salt is the only Highsmith novel in which no violent crime occurs.

Therese is not an eloquent or self-revealing character, and her dialogue with Carol is sometimes banal. Yet the novel is viscerally romantic. When Therese visits Carol’s home for the first time, Carol offers her a glass of warm milk that tastes of ‘bone and blood, of warm flesh, saltless as chalk yet alive as a growing embryo.’ The two women embark on a road trip, and the descriptions of it read like a noirish dream—stiff drinks, wood-panelled motel rooms, a gun in a suitcase. A detective hired by Carol’s husband pursues the couple, and you can feel Highsmith’s thriller muscles twitching to life.

The love story is at once hijacked and heightened by the chase story. Therese’s feelings, massing at the edge of her perception like the storm clouds out the car window, are a mystery to her. The weight of what goes unsaid as she and Carol talk about the towns they pass or where they might stop for breakfast builds in an almost ominous way.”

–Margaret Talbot, The New Yorker, November 30, 2015

*

The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955)

Anticipation! It occurred to him that his anticipation was more pleasant to him than the experiencing.

“An exciting rat-race with the principal rat in the title role is Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley.

Tom Ripley’s talent is for crime, and crime with variations is the melody played by the author. A more objectionable young man than Mr. Ripley could hardly be imagined. You certainly wouldn’t want to met him; but he is perfectly fascinating to read about.

Engaged by Dickie Greenleaf’s father to bring Dickie home from Paris, the talented Mr. R. follows his own instincts to make of the errand a protracted European holiday. The wiles with which he handles Dickie—and Dickie’s attractive girl—eventually involve him in a wild web of evasions and impostures and few murders have been more starkly cold-blooded or more chillingly described than those which arise out of his adventure.”

–Lockhart American, The Pittsburgh Press, December 4, 1955

“Patricia Highsmith is one of the most talented suspense writers this reviewer has encountered in some time. The Talented Mr. Ripley is a fine way to make her acquaintance if her previous Strangers on a Train and The Blunderer were missed.

In stories of this genre, the most frequently lacking quality is character delineation. Miss Highsmith can boast it as one of her strong points. Her protagonist is weakling Tom Ripley, a self-pitying, self-seeking individual who shows horrifying elements of strength when murder is involved—a murder to provide him with a life of ease and a second to cover up the first.

The setting is Italy, a country the author obviously knows well. Ripley attaches himself to rich Dickie Greenleaf and grows to love the good life too well to give it up. Murder is his solution and he takes on the dead Greenleaf’s identity.

This leads to all sorts of dramatic complications which for suspense’s sake are better left untold. This reviewer, after turning over the final page, is looking forward to Miss Highsmith’s next effort with anticipation.”

–Jack Owens, The Fort Lauderdale News, October 30, 1955

“Tom Ripley…is an American arriviste who reinvents himself as a Continental gentleman, a small-time con man who evolves into an urbane serial killer. By the end of these [first] three novels, Ripley has murdered more than half a dozen people—acts that barely cause a ripple in his conscience or genteel lifestyle. He is at once a less bizarre, more bourgeois version of Hannibal Lecter and an illustration of Highsmith’s deeply cynical view that all human beings are corruptible, that as one of her characters in Hitchcock’s adaptation of Strangers on a Train remarks, ‘Everyone is a potential murderer.’

…

“The Talented Mr. Ripley not only demonstrates Highsmith’s gift for using the genre conventions of the mystery novel to explore the existential ambiguities of identity, but it also attests to her keen gift for psychological insight. By chronicling the ordinary details of Ripley’s life and the logical workings of his mind, she forces us to re-evaluate the lines between reason and madness, normal and abnormal, while goading us into sharing her treacherous hero’s point of view.”

–Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times, November 19, 1999

*

Ripley’s Game (1974)

“I’ve thought of a wonderful way to start a forest fire,” Tom said musingly as they were having coffee.

“Tom Ripley—that amoral American living in Paris who owes his high style of living to the fact that he had literally gotten away with murder—has been snubbed by the host of a party he had recently attended, an Englishman named Jonathan Trevanny, who, as Ripley has found out, happens to be suffering from the early stages of leukemia. To Pay him back for the snub, Ripley decides to play a nasty little trick on Trevanny.

Approached by a criminal-friend, who wants to hire an ‘unconnected killer,’ Ripley suggests that his friend first trick Trevanny into thinking that his illness has taken a sudden turn for the worse, and then, when Trevanny is sufficiently worried, propose to him that he perform two murders for a fee that will leave his wife and son secure when he dies,

The narrative spotlight then switches to Trevanny, the mild, colorless proprietor of a picture-frame shop, whose only distinctive trait is devotion to his family. Bit by bit, the rumors of his declining health begin to get him down. Gradually, the prospect of committing the lucrative murders begins to strike him as plausible. The tension builds. Trevanny approaches his first victim. And we settle in for what will surely be a marvelous read.

But then, at the height of the climactic scene…Miss Highsmith blows the whole thing. She decides to bring Tom Ripley back to center stage, and since there is no reason whatsoever for him to be there, she must force him on us implausibly. From that point on the pieces of her novel fall further and further apart, and by the end the whole business has gotten so silly that it is difficult to recall what got us interested in the first place. Too bad; but maybe there’s a screenplay here somewhere.”

–Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, The New York Times, July 25, 1974

“…it tries to resurrect the theme of doppelgangers featured in The Talented Mr. Ripley and Strangers on a Train by pairing Ripley, the veteran killer, with a first-time murderer named Jonathan Trevanny. Trevanny is manipulated by Ripley and one of Ripley’s friends into believing that he is dying and then is induced to pull off a mob hit in return for a large sum of money. There is lots of hokey talk in this novel about the Mafia and guns and garrotes, and several bloody shoot-outs—none of which play to Highsmith’s psychological forte.

Worse, Ripley seems to have become an out-and-out madman: a sadist who will play a cruel joke on an ailing man simply because he dislikes the man’s manner; a thrill-seeking murderer who likes to celebrate his kills with a fine dinner or an expensive purchase. His marriage to the zombielike Heloise feels like a thorough sham—she is not the least bit nonplussed by his dabblings in murder and is equally unconcerned about the frequent threats to his safety—and their self-indulgent existence in the French countryside begins to feel like a lame parody of upper-class life.

Because it’s increasingly difficult for us to care about Ripley, the sense of complicity Highsmith wants to create between the reader and her characters dissolves. Instead of being immersed in their shadowy, venal world, as we were in The Talented Mr. Ripley, we are invited to feel smug and morally superior: a fatal flaw in just about any novel.”

–Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times, November 19, 1999

*

Little Tales of Misogyny (1975)

He realised what a horrible mistake, crime even, he had been guilty of in demanding such a barbaric thing as a girl’s hand.

“The 17 tales in Highsmith’s new collection are a far cry from Strangers on a Train and her other unforgettable thrillers. These stories, although written with exemplary style, make the flesh crawl but not pleasurably, as reliable suspense fare does. Each focuses on a female doing in a male or, more often, herself. ‘The Breeder’ Elaine persists in giving birth until her husband Douglas goes irrevocably mad, trying to support 17 children. ‘The Victim’ is Cathy, fond of claiming she’s been raped repeatedly in her nubile adolescence. During her career as an airline hostess, Cathy’s sexuality pays better in rich gifts than in sympathetic attention. But greed and vanity spell the lush girl’s doom. From the book’s overall tone, readers could infer that its origin was bitter contempt for humans of either gender. The entries fail as real satire, which is always amusing, regardless of its stings.”

–Publishers Weekly

“My first thought, before I started reading this overlooked collection, was that it would contain examples, informed by second-wave feminism, of men being nasty to women and being punished horribly by Patricia Highsmith. But by the time the 10th little tale rolled around—’The Fully Licensed Whore, or, The Wife’—I had become uncomfortably aware that most of the time it is the women who are ghastly, and often end up being killed off by Highsmith. The book was first published in 1975 in German, under the title Kleine Geschichte für Weiberfeinde, appearing in English two years later. I should have looked closer at that German title: it means, literally, ‘little tales for misogynists.’ This is not a book to teach the misogynists a lesson: it’s something you might give a misogynist on his birthday.

…

“…it occurred to me that the best way to appreciate this book would be as a string of extremely black jokes – in which case it works very well. After all, if there is anyone who knows how to jangle our moral nerves, from what often seems like pure authorial mischief, it is Highsmith. The mischief here extends to what at first glance looks like a single-minded assault on her own sex, until it becomes clear that what she is actually attacking is a range of stupid or vicious behaviours; the charge of misogyny is something of a red herring.

When this book first came out, many readers didn’t understand it, or chose not to. However Highsmith, sexually omnivorous, capable of cruelty, was in quite a few ways a character out of a Patricia Highsmith story. She couldn’t have written in any other way, and to criticise her for the well she drew her inspiration from is as unfair as to criticise someone for the face they were born with. This is not to denigrate her skill: every word is chosen with great care; not one is wasted.

Sometimes you need someone with an acidic vision to clear away the grime of familiarity and ease. It is not chance that among her many fans were Graham Greene, Gore Vidal and JG Ballard, or that she was resolutely unappreciated in her native United States. The majority of stories in this volume could be said to be indictments, and utterly merciless ones at that, of the suburban American dream of the mid-20th century. The critic Brigid Brophy called her a Dostoevsky “whose gifts include humour and charm”. I’m not so sure about the charm here, but these stories, once you get the hang of them, are very wicked, very funny and—this being Highsmith’s mission in life, as far as one can tell—very unsettling.”

–Nicholas Lezard, The Guardian, January 20, 2015