From the beginning men used God to justify the unjustifiable.

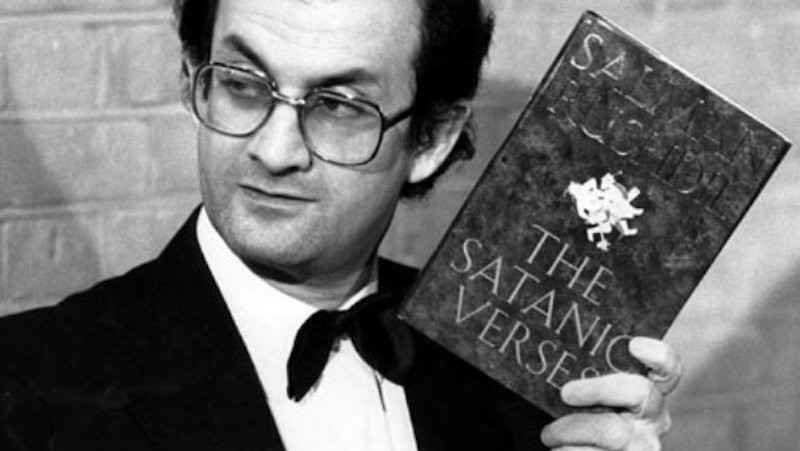

“The Satanic Verses has sparked bitter controversy among Muslims in South Africa, where the author was prevented from appearing at a book fair by arson and death threats against all concerned with the event. Last fall the importation of the British edition of the book was banned in India as a precautionary measure against religious leaders using it to incite their followers to sectarian violence. Recently, the publisher’s New York office has received several bomb threats and many angry letters.

As with Martin Scorsese’s film The Last Temptation of Christ, much of the outrage has been fueled by hearsay. Some of the noisiest objections have been raised by people who have never read the book and have no intention of ever reading it. This opposition does little to educate a woefully ignorant and prejudiced Western public about the Islamic faith. Banning the book only increases its notoriety: it answers nothing.

…

“It is Mr. Rushdie’s wide-ranging power of assimilation and imaginative boldness that make his work so different from that of other well-known Indian novelists, such as R. K. Narayan, and the exuberance of his comic gift that distinguishes his writing from that of V. S. Naipaul. In Salman Rushdie’s work, both India and England are repeopled and take on new shapes. For the Indian subcontinent there is a more commensurate bigness and teemingness, a registration of the pandemonium and sleaze of contemporary life. London neighborhoods suddenly leap to light as rich collages of transplanted Asian and African cultures. His fiction also takes on fashionable literary gestures—Joycean wordplay, magic realism and the hyperactivity, the ‘jouncing and bouncing’ of the Coca-Cola ads that typify American culture to much of the world. For the Western reader unfamiliar with Mr. Rushdie’s work, to what can this latest novel be compared?

In its entirety, it resembles only itself…

…

“Talent? Not in question. Big talent. Ambition? Boundless ambition. Salman Rushdie is a storyteller of prodigious powers, able to conjure up whole geographies, causalities, climates, creatures, customs, out of thin air. Yet, in the end, what have we? As a display of narrative energy and wealth of invention, The Satanic Verses is impressive. As a sustained exploration of the human condition, it flies apart into delirium as ‘pilgrimage, prophet, adversary merge, fade into mists, emerge.’ Does it require so much fantasia and fanfare to remind us that good and evil are deeply, subtly intermixed in humankind? And why then trouble ourselves about it? In a world of mirages, of dreams within dreams, what is death and what is life, and why should it matter to choose between them?

…

“What finally lingers, what lives most vibrantly, for this reader, are the scenes that are grounded—the places where magic doesn’t overwhelm the realism—the moments when Mr. Rushdie looks ‘history in the eye.”’

–A.G. Mojtabai, The New York Times, January 29, 1989