Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, a new feature in which books journalists from around the US share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recent gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic from a different part of the country, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

This week we spoke to freelance reporter and NPR contributing book critic, Annalisa Quinn

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

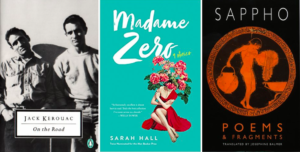

Annalisa Quinn: I guess the fantasy would be to time travel and then use my modern feminist interpretive tools to do critical kung fu on Jack Kerouac or whomever. Problematic! I’d shout, deliver a swift blow to the ribs, and then vanish back into my time machine. But that would obviously be cheating: part of the appeal of book reviewing is that you exist in roughly the same moment as the writer. That’s exciting and risky because you don’t have anyone else’s thoughts to mediate between you and the book. I think I do have this fantasy of an unmediated encounter with some of those works that have acquired so many centuries of interpretive buildup that it’s hard to really see them—though that buildup is sometimes almost as interesting as the text itself. But imagine hearing Sappho without all the grim moralizing of centuries to weigh her down.

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

AQ: Sarah Hall’s Madame Zero, which was well reviewed in the U.K. but got almost no press at all in the U.S. Her stories have this almost feline quality to them: graceful, enigmatic, quietly unsettling. I love the story “Mrs Fox” about a woman who turns into a vixen. The moment of transformation is so horribly vivid, but my favourite part is the first sentence: “That he loves his wife is unquestionable.” Pretending to reassure us, she instead creates this enveloping unease that lasts throughout the story: Why would someone question it? What’s going to happen to his wife?

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

AQ: I don’t know if I can really say what other people think, but I’ll mention some of the traps I think about and try to guard against. There’s a kind of standardized critical vocabulary divorced from the actual pleasure of sentences: words like lyrical, arresting, compelling, unflinching, tour-de-force, gemlike, rollicking, effervescent, etc, etc. And we can be staid and dutiful about it: plot summary, perfunctory minor criticism, then effusive adjective salad, ending with a grand imperative to the reader. But though book criticism, like everything else, has its conventions, it is so thrilling when you see the elastic possibilities of a really good critic working within a confined space.

I also try to remind myself that criticism isn’t the same as giving my opinion. It takes a lot of research—reading a writer’s back catalogue, sure, but also reading widely, picking up ideas, flipping through things, reading old books as often as new ones. That’s why it’s so nice to write in open stacks in a library—you can scrounge around.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

AQ: I’ll quote Milton’s Satan: “We know no time when we were not as now.” And by we, I mean me. I started writing after the advent of social media, and it’s weird and kind of upsetting to realize how hard I find it to imagine what writing looked like before the internet. As for social media specifically, I find it distracting, and sometimes useful, but not that important for my own thinking.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

AQ: Olivia Laing’s art writing is so humane and so thoughtful about the connections between private lives and wider social and cultural forces. I like Molly Young on fashion, Hilton Als on theatre, and Daniel Mendelsohn on classics. Dayna Tortorici has a rigorous, unpretentious intellect that I love to watch at work in her essays for n+1. I’ve also been really enjoying Vinson Cunningham’s writing because he has such range—sports and culture and books and politics. And then Parul Sehgal has this heightened sensitivity to words and their resonances that make her sentences almost seem to vibrate on the page. I love her “First Words” columns for the New York Times Magazine, which take individual words so seriously while always looking out into the wider world.

*

Annalisa Quinn is a freelance critic and reporter. She is a contributing book critic for NPR and has written for the New York Times Magazine, Financial Times, Guardian, Times Literary Supplement, and many other outlets.

**

Previous entires in this series:

Critic and NBCC board member Michael Magras

Vox staff writer and book critic Constance Grady

Poet, critic, and essayist David Biespiel

Writer, book critic, and host of The Other Stories podcast, Ilana Masad

Freeman’s editor and former NBCC President John Freeman

Editor, columnist, and NBCC board member Kerri Arsenault

The New Republic literary editor Laura Marsh

Heller McAlpin, contributor to Barnes & Noble Review, Washington Post, NPR, LA Times, and others

National Book Critics Circle President Kate Tuttle

Sam Sacks of The Wall Street Journal

Laurie Hertzel of The Minneapolis Star Tribune