The crux of the matter is whether total war in its present form is justifiable, even when it serves a just purpose.Does it not have material and spiritual evil as its consequences which far exceed whatever good might result? When will our moralists give us an answer to this question?

*

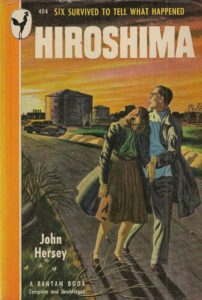

“American print journalism, possibly thanks to its special place in the US constitution, occasionally delivers exemplary knockout blows, world-class reporting on great subjects. John Hersey’s Hiroshima stands at the head of this tradition. These 31,000 words of searing testimony were written and published just a year after the dropping of the first A-bomb on Japan in August 1945, a terrible act of war that killed 100,000 men, women and children and marked the beginning of a dark new chapter in human history.

Hiroshima was the result of an inspired commission about an event of global significance from a renowned war correspondent by a magazine editor of genius. It was in the spring of 1946 that William Shawn, the celebrated managing editor of the New Yorker, and protege of its founder Harold Ross, invited his star reporter, John Hersey, to visit postwar Japan for an article about a country recovering from the shattering experience of the atomic bomb. The piece was intended to be a standard four-parter about Japan’s ruined cities and devastated lives nine months on from the country’s humiliating unconditional surrender.

“On the Pacific sea voyage to Japan, however, Hersey chanced on a copy of Thornton Wilder’s novel The Bridge of San Luis Rey, the tale of five people who are crossing an Inca rope bridge in Peru when it collapses, for which Wilder had won a Pulitzer prize. Accordingly, Hersey decided to focus his narrative on the lives of a few chosen Hiroshima witnesses. As soon as he reached the ravaged city, he found six survivors of the bombing whose personal narratives captured the horror of the tragedy from the awful moment of the explosion. This gave Hersey his opening sentence, a unique point of view, and a narrative thread through a chaotic and overwhelming mass of material. In a style later developed and popularised by the ‘new journalism’ of the 1960s, the opening of Hiroshima pitches the reader into the heart of the story, from the viewpoint of one of its victims:

At exactly 15 minutes past eight in the morning on 6 August, 1945, Japanese time, at the moment when the atomic bomb flashed above Hiroshima, Miss Toshiko Sasaki, a clerk in the personnel department of the East Asia Tin Works, had just sat down at her place in the plant office and was turning her head to speak to the girl at the next desk.

From here, Hersey embarks on an exploration of the lives of five other interlocutors: the Rev Mr Kiyoshi Tanimoto, of the Hiroshima Methodist church, who suffers radiation sickness; Mrs Hatsuyo Nakamura, a widow with three children; one European, Father Wilhelm Kleinsorge, a German Jesuit priest who had endured exposure to radiation; and finally, two doctors – Masakazu Fujii and Terufumi Sasaki (not related to Miss Sasaki). Some of these interviewees had been less than 1,500 yards (1,370m) from the site of the explosion, and their harrowing accounts of vaporised, burnt and mutilated bodies, of blasted survivors, of hot winds and a devastated city tormented by raging fires, a scene from hell, gave a voice to a people with whom the US and its allies had been brutally at war only a year earlier. Hersey’s brilliant reportage gave his story an existential dimension:

They still wonder why they lived when so many others died. Each of them counts many small items of chance or volition – a step taken in time, a decision to go indoors, catching one streetcar instead of the next – that spared him. And now each knows that in the act of survival he lived a dozen lives and saw more death than he ever thought he would see. At the time, none of them knew anything.

“Hersey also used all his skill as a novelist and as a war reporter to bring home the horror of what he, one of the first correspondents into Hiroshima, had learned:

Dr Sasaki had not looked outside the hospital all day; the scene inside was so terrible and so compelling that it had not occurred to him to ask any questions about what had happened beyond the windows and doors. Ceilings and partitions had fallen; plaster, dust, blood, and vomit were everywhere. Patients were dying by the hundreds, but there was nobody to carry away the corpses. Some of the hospital staff distributed biscuits and rice balls, but the charnel-house smell was so strong that few were hungry. By three o’clock the next morning, after nineteen hours of his gruesome work, Dr Sasaki was incapable of dressing another wound.

Hersey’s decision to use the testaments of Dr Sasaki, Mrs Namakura and the others, was both an inspired creative and also a tactically brilliant decision. The US army of occupation had prevented many US journalists from taking material out of the country, censoring photographs and tape-recordings alike. Hersey avoided such restrictions. He would stay only a few weeks in Hiroshima, but he returned to New York with a suitcase full of extraordinary first-hand material, and now set about fashioning a four-part piece for the New Yorker.

“Part I, A Noiseless Flash, introduced Hersey’s six witnesses. Part II, The Fire, reported the immediate, horrific aftermath of the explosion. Part III, Details are Being Investigated, described the wider, Japanese response to this unimaginable act of war. Part IV, Panic Grass and Feverfew, followed Father Kleinsorge and the sufferings of Hersey’s other witnesses in the weeks after the bombing, describing the Japanese people’s hatred for the Americans who had perpetrated this ‘war crime.’ So soon after the end of the second world war, with feelings still running high, to achieve any kind of objectivity was a remarkable challenge.

In hindsight, Hersey frankly acknowledged the first technical difficulty he encountered with this story: there was no way he could bring his usual style to bear on his material, he said. ‘A show of passion would have brought me into the story as a mediator. I wanted to avoid such mediation, so the reader’s experience would be as direct as possible.’ Instead, he went for cool and low key. As the New Yorker writer Hendrik Herzberg has written: ‘Hersey’s reporting was so meticulous, his sentences and paragraphs were so clear, calm and restrained, that the horror of the story he had to tell came through all the more chillingly.’ Hersey’s flat, plain, deliberately unemotional style immediately caught the imagination of his editors, Ross and Shawn. In conditions of great secrecy, they decided to do something unprecedented: devote an entire edition of their magazine to the story of Hiroshima.

The ironic cover of the 31 August 1946 edition of the New Yorker gives nothing away: a summer-in-the-park illustration of a carefree picnic. It was not until the reader turned past Goings on About Town and the usual metropolitan advertisements for motor cars and diamonds that the editors’ intentions were revealed in a simple statement: ‘TO OUR READERS. The New Yorker this week devotes its entire editorial space to an article on the almost complete obliteration of a city by one atomic bomb, and what happened to the people of that city. It does so in the conviction that few of us have yet comprehended the all but incredible destructive power of this weapon, and that everyone might well take time to consider the terrible implications of its use.’

The impact of this New Yorker was extraordinary. The edition sold out 300,000 copies within hours of publication, inspiring a storm of commentary across the US, and abroad, especially on radio. Harold Ross said he had never got ‘as much satisfaction out of anything else’ in his life. Hersey’s piece was reprinted worldwide. Albert Einstein, an outspoken opponent of the bomb, who tried to buy a thousand copies of the New Yorker to send to fellow scientists, had to settle for a facsimile version. Copies of the original edition changed hands at many times the cover price.

The New Yorker’s rival, Time magazine, gave the best immediate verdict:

Every American who has permitted himself to make jokes about atom bombs, or who has come to regard them as just one sensational phenomenon that can now be accepted as part of civilisation, like the airplane and the gasoline engine, or who has allowed himself to speculate as to what we might do with them if we were forced into another war, ought to read Mr Hersey. When this magazine article appears in book form the critics will say that it is in its fashion a classic. But it is rather more than that.

Within a year, Knopf had published Hiroshima as a book. It has never since been out of print, and has now sold upwards of 3m copies.

John Hersey returned to Hiroshima in 1985 to meet his informants once again, and to write a retrospective, The Aftermath, which described the postwar lives of the hibakusha*. Mr Tanimoto, he wrote, still ‘got up at six every morning and took an hour’s walk with his small woolly dog, Chiko. He was slowing down a bit. His memory, like the world’s, was getting spotty.’

* In referring to those who went through the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, the Japanese tended to shy away from the term ‘survivors,’ because in its focus on being alive it might suggest some slight to the sacred dead. The class of people to whom Hersey’s witnesses belonged came to be called by the more neutral name hibakusha – literally, ‘explosion-affected persons.’ For more than a decade after the bombings, the hibakusha lived in an economic limbo, apparently because the Japanese government did not want to find itself saddled with anything like moral responsibility for heinous acts of the victorious US.”

–Robert McCrum, The Guardian, September 19, 2016