I am what time, circumstance, history, have made of me, certainly, but I am, also, much more than that.

So are we all.

*

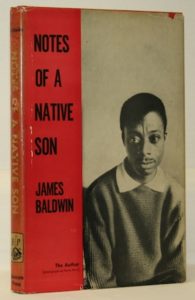

“I think that one definition of the great artist might be the creator who projects the biggest dream in terms of the least person. There is something in Cervantes or Shakespeare, Beethoven or Rembrandt or Louis Armstrong that millions can understand. The American native son who signs his name James Baldwin is quite a ways off from fitting such a definition of a great artist in writing, but he is not as far off as many another writer who deals in picture captions of journalese in the hope of capturing and retaining a wide public. James Baldwin writes down to nobody, and he is trying very hard to write up to himself. As an essayist he is thought-provoking, tantalizing, irritating, abusing and amusing. And he uses words as the sea uses waves, to flow and beat, advance and retreat, rise and take a bow in disappearing.

In Notes of a Native Son, James Baldwin surveys in pungent commentary certain phases of the contemporary scene as they relate to the citizenry of the United States, particularly Negroes. Harlem, the protest novel, bigoted religion, the Negro press and the student milieu of Paris are all examined in black and white, with alternate shutters clicking, for hours of reading interest. When the young man who wrote this book comes to a point where he can look at life purely as himself, and for himself, the color of his skin mattering not at all, when, as in his own words, he finds ‘his birthright as a man no less than his birthright as a black man,’ America and the world might as well have a major contemporary commentator.

Few American writers handle words more effectively in the essay form than James Baldwin. To my way of thinking, he is much better at provoking thought in the essay than he is arousing emotion in fiction. I much prefer Notes of a Native Son to his novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, where the surface excellence and poetry of his writing did not seem to me to suit the earthiness of his subject matter. In his essays, words and material suit each other. The thought becomes poetry, and the poetry illuminates the thought.

What James Baldwin thinks of the protest novel from Uncle Tom’s Cabin to Richard Wright, of the motion picture Carmen Jones, of the relationships between Jews and Negroes, and of the problems of American minorities in general is herein graphically and rhythmically set forth. And the title chapter concerning his father’s burial the day after the Harlem riots, heading for the cemetery through broken streets—’To smash something is the ghetto’s chronic need’—is superb. That Baldwin’s viewpoints are half American, half Afro-American, incompletely fused, is a hurdle which Baldwin himself realizes he still has to surmount. When he does, there will be a straight-from-the-shoulder writer, writing about the troubled problems of this troubled earth with an illuminating intensity that should influence for the better all who ponder on the things books say.”

–Langston Hughes, The New York Times, February 26, 1958