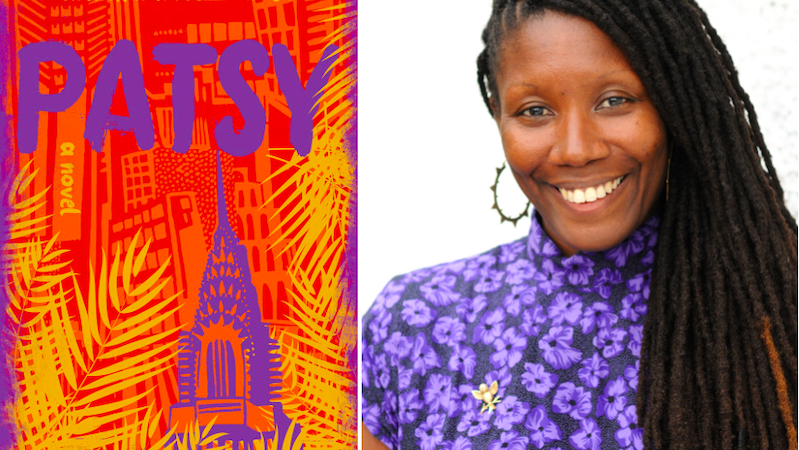

Nicole Dennis-Benn’s Patsy is published today. She shares five books about Immigrants.

The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri

This novel, one of the first books I read about immigrants, is a coming-of-age story that delves into identity and acculturation. I fell in love with the way Lahiri writes about the painful assimilation process we immigrants go through. I’m captivated by Jhumpa Lahiri’s writing and the care and compassion she gives to her characters.

Jane Ciabattari: One of the elegant and resonant elements of this novel of immigrant identity is her main character’s name switch. Gogol, and then Nikhil. “It is as Nikhil,” she writes, “that he grows a goatee, starts smoking Camel Lights at parties and, while writing papers and before exams, discovers Elvis Costello and Brian Eno and Charlie Parker.” What passages strike you as illuminating that shifting sense of identity, and a moment of “belonging,” even if temporary.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: I was really taken by the chapters with Maxine, the American woman Gogol started dating after graduate school. I was particularly taken by how he assessed her life as a privileged white American and those of her very affluent parents, comparing them to his own immigrant Bengali parents. That storyline struck me, because as immigrants, we are always comparing ourselves to that which represents the American Dream—upper-middle class whiteness. That’s the image we see in the media, and that’s the image that gives many people from other countries hope that we can come to America and be like “them.” I have American friends who are still in awe that we had American channels in Jamaica, clearly ignorant of the fact that cultural globalization is real and that America is viewed all over the world. Therefore, many immigrants have fantasies about being American from those shows we watched on cable television, thinking all Americans look like that. Almost always, those shows depict whiteness in a way that make us empathize with and desire those characters and their lives. I, like Gogol, entertained such a fantasy before realizing that they would never accept and love us. We will always be rendered “other” in their eyes. And that can be very disappointing, to say the least.

We Need New Names by NoViolet Bulawayo

This is another coming-of-age story. I love NoViolet’s characters and how she uses the voice of a young girl, Darling, to unflinchingly relay issues that many of us would rather look away from. Bulawayo depicts the beauty as well as the ugliness of a country ravaged by poverty, and shows the hopelessness of a girl arriving in America only to lose her way in life, as well as the people she loves.

JC: Darling, caught between Zimbabwe and America, feels both a traitor and a newcomer. “In America, roads are like the devil’s hands, like God’s love, reaching all over, just the sad thing is, they won’t really take me home.” Do you think it’s possible Darling might ever feel she belongs in her new home?

ND-B: I don’t think Darling will ever feel a sense of belonging in her new home. First of all, like my character, Patsy, Darling is undocumented, which means she’s basically living as invisible in the system. Though many undocumented immigrants survive that way in America, they constantly live in fear of being deported. There are also less opportunities for them to gain upward mobility in a country where having a social security number is crucial. One doesn’t feel a sense of belonging in situations like that; one feels more like an interloper.

Breath, Eyes, Memory by Edwidge Danticat

Edwidge Danticat, who writes about Haiti with compassion and beauty, is my biggest inspiration. I’ve learned much from her, particularly in how she draws clear pictures of peoples’ lives, both before and after leaving the island. In Breath, Eyes, Memory, a young girl leaves Haiti to live with her mother, who is as foreign to her as America itself. It’s a riveting novel that taps into the generational traumas we carry, even across oceans.

JC: “I come from a place where breath, eyes and memory are one, a place where you carry your past like the hair on your head,” Danticat writes. Her narrator, Sophie, is born of her mother Martine’s rape, and raised by her aunt until age 12, when she joins her mother in New York. In what ways does Danticat express Sophie’s dislocation, which is both geographical and personal?

ND-B: Sophie’s dislocation is quite obvious throughout the entire book. We’re talking about a twelve-year-old girl who is sent to live with her mother in a foreign place. Any child would be terrified of such a huge shift. One would think that the child going to live with her mother would be a good thing, but Danticat throws a wrench in that thinking by giving us the circumstance of Sophie’s birth—the fact that she looks like her father, the man who raped her mother, and thus exacerbates her mother’s nightmares. This casts a dark shadow over the narrative, which gets darker and darker the more we learn about the traumas in the form of “testing” that these women have lived with. Ultimately, we find out that the dislocation we speak of is more than the jarring move to another country to live with a stranger, but one entrenched in personal violations.

Another Brooklyn by Jacqueline Woodson

This novel about girlhood, set in Brooklyn in the 1970s, captivated me. I appreciate the poetry in Woodson’s writing, and especially the sparseness in which this story is told. It’s about a young Tennessee transplant named August who, after moving to Brooklyn following her mother’s death, forged an intimate relationship with three other girls in a quest for companionship and survival in a place with “teeth as sharp as razors.”

JC: The refrain “This is memory” echoes through Another Brooklyn. Why is memory so important to the narrative?

ND-B: Memory is not only important to this narrative but all our narratives. It’s the only thing that is ours alone. For August, who had lost her mother and struggled to navigate a new life in Brooklyn as a young woman in a realm that conspires to rob girls of our bodies, our voices, and our stories, all August had, really, was her memory. She narrated this story with authority, claiming ownership of it, and reminding us constantly that “This is mine.”

The Terrible by Yrsa Daley-Ward

This book, an unapologetic account of surviving girlhood, is the only memoir on my list. Daley-Ward was raised by a young mother—a Jamaican immigrant in the UK—who sought love in all the wrong places while raising two children. Yrsa writes movingly and deeply about love, loss, and the discovery of self.

JC: I remember opening this book, reading the first line, “My little brother and I saw a unicorn in the garden in the late nineties …” and reading it to the end standing up. She has such a powerful voice. What makes it so compelling?

ND-B: Yrsa’s vulnerability in this memoir was really what sold me. Very rarely do I encounter books by women, particularly black women, who are willing to bare their souls on issues such as parental abandonment, sexual exploits, and struggles with mental health and addiction. Though Yrsa Daley-Ward’s story is mostly a painful one, her poetic words make it easier to digest.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·