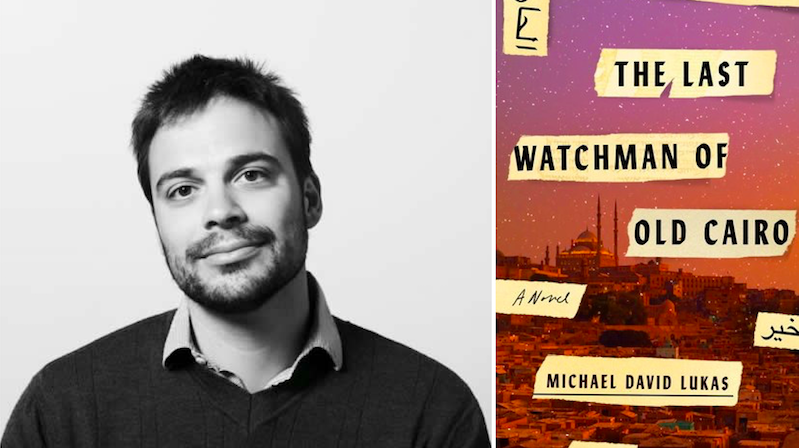

Michael David Lukas’s new novel, The Last Watchman of Old Cairo, has just been published by Spiegel & Grau. We asked the novelist to talk about five books in his life and he chose the ones listed below, about building cultural bridges.

*

Ghassan Kanafani, Palestine’s Children

“Politics and the novel,” Kanafani once said, “are indivisible.” A spokesman for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine who was killed in a car bomb in 1972, Kanafani is not often thought of as a bridge-builder. But sometimes bridges appear where you least expect them. In fifteen loosely linked stories, the collection offers a powerful, multifaceted, and unapologetic take on the Palestinian experience immediately following the creation of the state of Israel. Most of the stories center on the anger, despair, and hope of children trying to grapple with displacement. The final novella, “Returning to Haifa,” follows a young Palestinian couple as they return to their former home, nineteen years later, only to discover that the infant son they left behind is now an Israeli soldier.

Jane Ciabattari: The final novella in particular seems to offer the biggest challenge; what makes it work?

Michael David Lukas: One of the things I most admire about “Returning to Haifa” is its ability to balance the heavy metaphor at the heart of the story (the infant son as Palestine/Israel) with the characters’ complex humanity. Kanafani pulls it off, I think, because he fully embraces both. He creates full and unique characters that the reader can connect to, without ever shying away from the story’s symbolic resonance.

Amitav Ghosh, In an Antique Land

Subtitled “A history in the guise of a traveler’s tale,” Ghosh’s third book traces the thread of a story he picked up while researching his doctoral dissertation in a small rural Egyptian village. Combining his own ethnographic fieldwork with the story of a twelfth-century Egyptian-Jewish merchant and his Indian slaves, the book uses documents found in the Cairo Geniza to weave a fascinating portrait of the medieval Mediterranean world in all its diversity, complexity, and interdependence.

JC: How did you first hear of the Cairo Geniza? And what did Ghosh’s book add to research you did for The Last Watchman of Old Cairo?

MDL: In an Antique Land was the first book I read about the Cairo Geniza and it hooked me from the start. It’s hard to overstate the book’s importance to my research process. I may have leaned more heavily on other books (like S.D. Goitein’s A Mediterranean Society) when it came to checking facts. But Ghosh’s vivid descriptions of medieval Cairo as a cosmopolitan economic hub where merchants and scholars traded goods and ideas with people from Paris to Baghdad to Mumbai, are inseparable from my own vision of the place.

Zadie Smith, NW

Smith’s third novel traces four very different Londoners as they attempt to make their way through, understand, and/or escape Kilburn, the working-class neighborhood where they all grew up. A novel about bridges and walls, the things that facilitate and obstruct connections within this neighborhood and all neighborhoods, NW loops back on itself continually, with each new narrator answering and complicating questions raised by previous sections.

JC: How does NW exemplify the polyphonic approach we’re seeing in so many novels today, including your own?

MDL: Like many other polyphonic novels—Building Stories by Chris Ware or Gods Without Men by Hari Kunzru, for example—NW uses place as its guiding principle. But the story is about much more than one relatively small neighborhood in Northwest London. With her characteristic deftness and empathy, Smith uses the microcosm of Kilburn to say something much larger about difference and city life and the hybridity we all embody in one way or another

James Baldwin, Another Country

Set in 1950s Greenwich Village, Another Country skips between a half-dozen different points of view to tell the story Rufus Scott, a tortured jazz drummer who commits suicide by jumping off the George Washington Bridge. In the wake of Rufus’ death, we follow the entanglement and eventual dissolution of his friends, lovers, relatives, and colleagues, all trying in their own way to understand his life and afterlife. Controversial at the time for shattering taboos about interracial relationships, sexuality, and infidelity, the book offers a beautiful and brutally tragic take on questions of belonging, identity, and the corrosive effects of racism.

JC: Baldwin also takes a polyphonic approach in this novel. Do you see a connection between Zadie Smith and Baldwin, and the culture each is bridging? Echoes?

MDL: Yes, definitely. Both novels are deeply, inexorably rooted in place. They are both novels about cities and the ways that proximity both flattens and exacerbates difference. They are both books about encountering the other and making community across boundaries of class and race. I imagine Smith thought about Another Country when she was writing NW. But it doesn’t feel to me like an homage, in the way that On Beauty mirrors the structure of Howard’s End. In spite of their similarities, they are very different books, each with its own unique rewards.

Margaret Atwood, MaddAddam Trilogy

One might say that Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy—Oryx and Crake, The Year of the Flood, and MaddAddam—builds a bridge to the future. But it’s not a bridge anyone in their right mind would want to cross. Like all good post-apocalyptic fiction, the trilogy takes a seamcutter to our societal divisions, then begins to stitch them back up again in a new fashion. It’s bleak and yet oddly life-affirming. After reading more than a thousand pages about pandemic and social division, doomsday cults, profit-minded gene splicing, and uber-violent video games, one comes away feeling oddly hopeful about humanity.

JC: What is it about Atwood’s books that gives them the mysterious quality of imbuing hope? What’s the secret to maintaining optimism when it seems cultural chasms are unbridgeable?

MDL: No matter how bleak her dystopias may be (and they can be pretty bleak) Atwood always gives us a shard of humanity to hold onto, a tool we can use to build a new future. As far as I see it, the present moment might be bleak, but the seeds of that future are already beginning to sprout. Those seemingly unbridgeable cultural chasms are more about ideologies of division than any inherent difference. Which isn’t to say that division doesn’t exist. It does. But the way to combat that division is by unmasking the lie behind it. Which is exactly why we need stories about building bridges.

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.