Welcome to Shhh…Secrets of the Librarians, a new series (inspired by our long-running Secrets of the Book Critics) in which bibliothecaries (yes, it’s a real word) from around the country share their inspirations, most-recommended titles, thoughts on the role of the library in contemporary society, favorite fictional librarians, and more. Each week we’ll spotlight a librarian—be they Academic, Public, School, or Special—and bring you into their wonderful world.

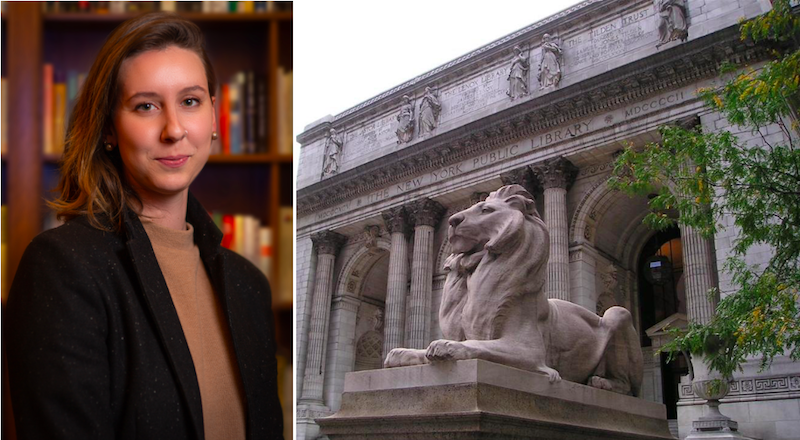

This week, we spoke to the curatorial associate for the Polonsky Exhibition of The New York Public Library’s Treasures, Mary Catherine Kinniburgh.

*

Book Marks: What made you decide to become a librarian?

Mary Catherine Kinniburgh: Being a researcher cultivated my admiration for librarians, and eventually, my choice to work professionally within libraries. Of particular influence: during my doctoral degree, I was an editor for Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative, a project based within the Center for the Humanities at the Graduate Center. Lost & Found publishes archival documents as chapbooks, and gave me a sense of how important it was to work with libraries, archivists, and authors to share primary source work more widely. After an extensive research trip to study the poet Diane di Prima in the archives of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, I sat in the airport and applied to a page position in the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English Literature at The New York Public Library. I’ve been extremely lucky for that door that opened, and the ones since.

BM: What book do you find yourself recommending the most and why?

MCK: My teaching and research encourages us to look at different histories of printing and publication, especially those outside of mainstream contexts, to understand not only the technologies of print but how these create change in the world. One of the texts that really opened this field up for me is Rodney Phillips’ and Steve Clay’s A Secret Location on the Lower East Side: Adventures in Writing, 1960-1980, published by Granary Books and The New York Public Library. It exhaustively chronicles small press printings, mimeos, little magazines, and other ephemeral publications in a particularly vibrant era of American poetry—and because of The New York Public Library’s vast collections, you can cross-reference almost any item in the Berg Collection as a researcher. This type of encyclopedic history of non-institutionalized work reminds us of the fact that anyone can make literary history if they’ve got the mind (and mimeograph!) to do it, and this is ultimately political in the sense that people have the power to write, share, and create change and community through their work. Chronicling how this happens is our shared responsibility as institutions and researchers.

BM: Tell us something about being a librarian that most people don’t know?

MCK: We don’t use white gloves to handle archival or rare materials! While certain photographic materials do require you to wear gloves, for most materials it’s best to use clean hands. Gloves reduce dexterity, so for particularly fragile materials, your ungloved hands will be most sensitive and responsive to the material. You can learn more about this on a blog post at the British Library, and bonus: this is a hot topic on rare book Twitter, and there’s definitely a meme or two.

BM: What is the weirdest/most memorable question you’ve gotten from a library patron?

MCK: Most questions in special collections are about our own idiosyncratic procedures, as opposed to researcher “weirdness.” Special collections are known for having an intimidating aura—you have to share a research statement, register as a reader, and work in a supervised room with objects that have specific handling guidelines. And while special collection reading rooms do have similar protocol at times (such as only pencils, for the safety of materials!), the procedures for access and use are always slightly different. This means that while you may feel like a pro in one room, in the next you may feel like a first-time researcher. So: all questions are good questions, because I want researchers to feel comfortable and empowered to get what they need, and confident in handling rare materials.

In terms of memorable: the Berg Collection holds a letter opener that belonged to Charles Dickens, which is made with his beloved cat Bob’s taxidermied paw. I’ll let your imagination run wild on the questions that come with that one.

BM: What role does the library play in contemporary society?

MCK: In a library, you can read whatever you want and this information can’t be sold or shared with third parties. In a library, you can obtain access to the primary source documents of history—drafts of your favorite poet, or a first edition of your favorite book—and handle them yourself, connecting through touch and reading with our collective history. In a library, you can search through collections to put together the pieces of history in a new way, to find out for yourself what the story is. And in a library, you’ve got the space and resources to sit, write, think, be, and even speak and present: to convey what you find to your community and a broader public.

BM: Who is your favorite fictional librarian?

MCK: I’m obsessed with the real ones these days! I’m particularly interested in the imaginative work that expands our idea of who a “librarian” is—with full respect to the technical knowledge obtained through library science degrees or formal education, or other variants, I think there is plenty of room to value diverse forms of institutional and non-institutional expertise when it comes to assembling and managing knowledge. I just finished a dissertation that studies postwar American poets, like Charles Olson, Diane di Prima, and Gerrit Lansing, who collected large libraries (and were thus librarians, or curators), especially of occult literature. I write about what we might learn from examining and preserving these types of libraries—which are very creative in how they categorize knowledge. And I’m especially excited by the possibilities of what happens when we consider poets a specific type of information expert, or even the poetics of information more broadly.

*

Mary Catherine Kinniburgh is curatorial associate for the Polonsky Exhibition of The New York Public Library’s Treasures. She received her Ph.D. from The Graduate Center, CUNY, where she taught at Brooklyn College and served as an editor for Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·